When Arnold Rampersad’s biography of Langston Hughes, The Life of Langston, was published in 1986, its treatment of sexuality almost immediately ignited controversy. “As for the increasingly fashionable tendency to assert, without convincing evidence, that Hughes was a homosexual,” Rampersad wrote, “I will say at this point only that such a conclusion seems unfounded, and that the evidence suggests a more complicated sexual nature.” Three years later, Isaac Julien’s film Looking for Langston claimed Hughes as queer, to the applause of the Black gay poet Essex Hemphill. In 1993, queer studies scholar Scott Bravmann criticized Rampersad for requiring conclusive evidence that Hughes slept with men when he didn’t do the same regarding Hughes’s presumed heterosexuality. Four years later, Charles Nero took issue with Rampersad’s reliance on Hughes’s not wanting to be considered gay; that hardly constituted proof, Nero observed, that Hughes did not desire men. At issue for all of Rampersad’s dissenters was the politics of sexuality—in this case, the ways in which heteronormativity obscures queerness.

Also at issue was the politics of the archive. Rampersad’s two-volume biography drew from Hughes’s public and private writings. But those archival documents, the dissenters pointed out, were also influenced by the politics of sexuality. If a writer fears retribution for being queer, then that writer may not record such desires in a diary. In this light, the very documents that scholars read to understand the past may misrepresent or obscure the sexuality of people in an earlier era.

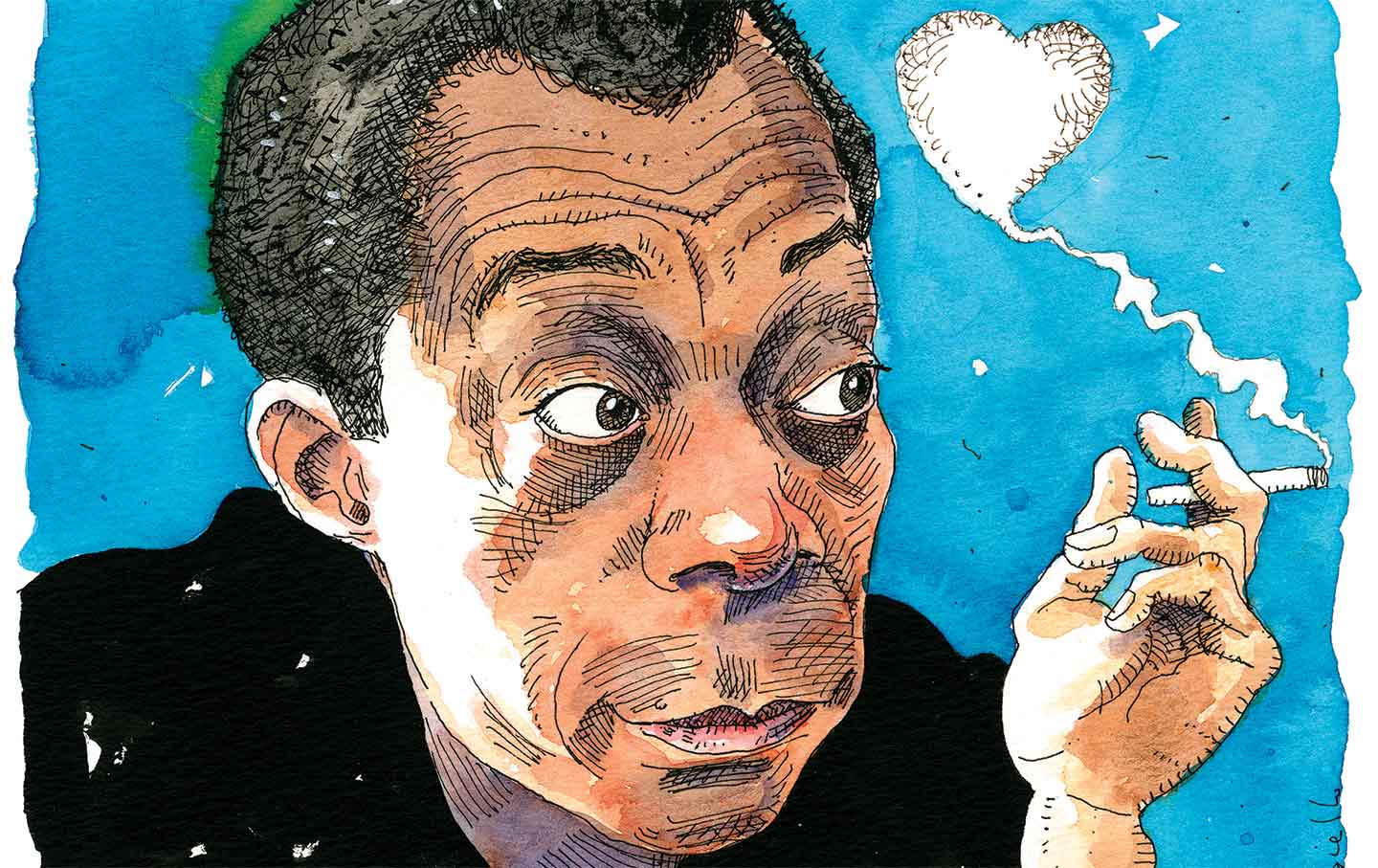

Because heteronormativity can influence both the scholar and the archive, these challenges pervade almost all historical and biographical writing, even when it comes to someone like the author James Baldwin, who chronicled some of his gay relationships but certainly not all of them. It has been rumored, for example, that Baldwin slept with Marlon Brando and the Turkish actor Engin Cezzar, but neither ever confirmed such a liaison. Several esteemed critics and one close associate of Baldwin have written biographies of the man, and yet so many of his loves—lost and won—remain an open question. Though one may turn to a biography to learn more about a historical figure’s private life, even the most painstakingly researched biography may still be unable to provide complete insight.

When it comes to Baldwin, his private life proves especially important because the politics of love were as central to his thinking as to his romantic life. Much of his writing—his novels, criticism, plays, and essays—were born out of his private experiences as much as his public ones. And his public life, from Eldridge Cleaver’s homophobic criticisms of Baldwin to his treatment by the FBI, often revolved around his private life—namely, his being gay. As a result, the challenge for the Baldwin biographer is to marry the public Baldwin with the private one.

This difficult task is what the writer Nicholas Boggs has set for himself in his new book, Baldwin: A Love Story. Boggs’s biography is a study of Baldwin in both his public and his personal life—his writings, his political activism, his relationships, his hopes, and the effect of each of these on the rest. Drawing on Baldwin’s letters and his and others’ autobiographical writings, as well as on interviews with those who knew him—including the first lengthy interview with Baldwin’s lover and collaborator Yoran Cazac—Boggs’s biography demonstrates the centrality of love to all aspects of Baldwin’s life. His experiences of love and his belief in its overriding power made it possible for him to write, to think, and to participate in movements for social change. The man who theorized, in The Fire Next Time, that love could solve what was then called the “Negro problem” came to this conclusion not only in the face of the harrowing amounts of hate he found in American society, but also through the abundance of care, generosity, and friendship he found in his private life. Baldwin’s beloveds helped him recover from suicide attempts. They helped him learn to accept himself and his sexuality. And they helped him find hope in the cross-cultural and interracial relations that, in Boggs’s telling, cemented his belief in the possibility of a better tomorrow.

Love was what funded Baldwin’s travels and provided him with hospitality; it was what gave him the time and energy to write essays on American racism, on the civil rights movement, and on Hollywood, to say nothing of his half-dozen novels. Love was what took Baldwin to the Swiss Alps, to the Turkish countryside, and often back to a United States that otherwise tended to make him feel unwelcome. Love was what drew him out of a cocoon of pessimism and frustration and back into public life, whether to discuss race relations on talk shows, to speak at rallies for incarcerated Black Power organizers, or to meet with then–Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy. While Baldwin was persecuted in part because of whom he loved, it was love that impelled him to attempt to bring about a more utopian future in which such persecution was not possible.

Born in 1924 to a financially insecure family in Harlem, Baldwin was fortunate enough to meet others who expanded his horizons. Recognizing his promise, his sixth-grade teacher Orilla “Bill” Miller took Baldwin to see Orson Welles’s all-Black production of Macbeth and delivered food to his family after Baldwin’s father lost his job. In junior high, another teacher, the Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen, encouraged Baldwin to apply to the magnet school DeWitt Clinton, where he enrolled in 1938. There, Baldwin joined the staff of the school’s literary magazine alongside Richard Avedon (who became an acclaimed photographer), Sol Stein (who became a publisher), and Emile Capouya (who became an editor at The Nation). Though his family struggled financially, and though Baldwin had regular run-ins with the police, his caring mentors and peers—along with his own determined willfulness—provided him an entrée into the world of arts and letters.

As a young closeted gay man, Baldwin developed a friendship with the painter Beauford Delaney, who introduced him to New York City’s queer, interracial artistic milieu—one that would buoy his spirits and help launch his career. At Capouya’s recommendation, a 16-year-old Baldwin, after sweeping the floors at a downtown sweatshop, visited Delaney’s studio in Greenwich Village and met the man who, as Baldwin later wrote, offered “walking, living, proof, for me, that a black man could be an artist.” The two became fast friends: Delaney played blues records for Baldwin, took him to galleries, and escorted him to Marian Anderson’s dressing room after a Carnegie Hall concert. Delaney even painted Baldwin nude, Boggs writes, in a piece that hinted at the artist’s “growing love for his new protégé,” a love “that was interwoven with a reticent yet unmistakable eroticism.”

When life proved difficult for Baldwin, Delaney often came to the rescue. In 1943, a year after Baldwin graduated from high school, his father died on the same day his mother birthed her ninth child; Delaney helped finance the funeral. In the aftermath of his father’s death, Baldwin bounced from job to job, and Delaney offered him a place to stay. Newly settled, Baldwin came out to Capouya and befriended Eugene Worth, a member of the Young People’s Socialist League. He and Worth, Baldwin wrote, “carried petitions about together, fought landlords together, worked as laborers together…and starved together.” During this time, Baldwin also met Richard Wright, who recommended him for an award based on his burgeoning fiction.

Baldwin may have fallen in with a sometimes supportive set, but his years downtown nevertheless wore on him. “Racially, the Village was vicious,” he recalled, “partly because of the natives, largely because of the tourists, and absolutely because of the cops.” In 1946, Worth died by suicide. Baldwin blamed himself, since Worth had confessed his love for him and Baldwin had not reciprocated because he considered love a “useless pain.” Baldwin began publishing book reviews, essays, and short stories, making something of a name for himself in New York—but he also started to dream of Paris, where Wright had recently moved. After winning a $1,500 Rosenwald Fellowship, Baldwin left the United States in 1948.

Postwar Paris offered Baldwin both dangers and opportunities. On his first day in the city, he met Wright at the café Les Deux Magots. Wright helped him find a room, though Baldwin left it for a cheaper one at the Hôtel Verneuil. There, he and his fellow bohemians shared “rooms, clothes, money, alcohol, and weed.” Baldwin also became a regular at La Reine Blanche, a queer cruising bar. His late nights soon began to take a toll: He ate too little and drank and smoked too much, and fell ill in 1949. But Baldwin’s illness turned out to be a blessing. His solitude provided him the time and space to work on an essay, “Everybody’s Protest Novel.” That landmark piece critiqued Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Native Son, and other works of “protest” literature for caricaturing Black life to advance political claims. The essay also, Boggs argues, helped Baldwin develop his literary aesthetics.

Though “Everybody’s Protest Novel” caused a stir, it also left Baldwin isolated by fracturing his relationship with Wright, who accused Baldwin of betraying him to advance his own career. Later that year, Baldwin was arrested in connection with a friend’s theft. Though he was eventually found not guilty, his incarceration and his overall circumstances left him so dejected that he tried to kill himself. His essay had announced his literary arrival, but his life had almost ended as a result.

As would become something of a pattern for Baldwin after a misfortune or tragedy, he rededicated himself to his personal and professional ambitions. He found a new lover, Lucien Happersberger, and continued working on a piece of fiction that advanced the principles he’d valorized in “Everybody’s Protest Novel”—one that did not sacrifice Black people’s humanity for the sake of politics. His romantic and literary lives proved harmonious. In his visits to Happersberger’s family chalet in the Swiss Alps, domestic harmony provided Baldwin the stability to complete the novel under a new title: Go Tell It on the Mountain.

Published in 1953, Go Tell It on the Mountain chronicles the coming of age of its protagonist, John Grimes, under the repressive and sometimes violent thumb of his father, a preacher in Harlem. The semi-autobiographical novel goes on to describe John’s father’s encounters with Southern racism and his mother’s close brush with police violence, contextualizing the difficulties of John’s maturation in a history of anti-Black degradation. The novel’s lengthy representation of each character’s interiority, combined with its critical portrait of structural racism, achieved the aesthetic aims that Baldwin had set out in “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” while the many positive reviews made it clear that he had finally supplanted Wright.

Even as Baldwin became more successful, however, love continued to elude him. Happersberger supported Baldwin’s career, but the two separated because Lucien had gotten a woman pregnant and Baldwin encouraged him to marry her. Without Lucien, he had little reason to remain in Europe. So he returned to New York in 1954, to mixed results. Baldwin received Guggenheim and MacDowell fellowships and completed a Yaddo residency, for which Lionel Trilling had recommended him. But the city did not seem to notice his newfound professional success. The police profiled and arrested Baldwin, and he spent a night in jail. At Baldwin’s invitation for an all-expenses-paid trip, Happersberger came to the city, but the visit was far from an ideal reconciliation: The police frisked them both, and Happersberger began seeing wealthy women. Baldwin again sought distance.

“The familiar yearning for and frustrations with Lucien,” Boggs writes, “spurred his creativity onward once again.” Baldwin was working on Giovanni’s Room, which he described in a letter as a “grim fable of helpless isolation, sexual terror, guilt, death, and acceptance as being most affirmative.” Dedicated to Happersberger, the novel told the story of a short-lived romance between David, a white American, and Giovanni, a white Italian, in Paris. Its unashamed portrait of queer love from the perspective of a closeted man foregrounds the notion that, as Baldwin later put it, “the discovery of one’s sexual preference doesn’t have to be a trauma. It’s a trauma because it’s such a traumatized society.”

The novel’s refusal to stigmatize its queer characters was poorly received at first. When Baldwin submitted it to his agent, she told him to “burn it,” Baldwin recalled. (The agent later claimed otherwise.) Baldwin then sent the book to Knopf, which refused the novel, in his view, because the publisher did not want to ruin his career. But he did eventually publish it in 1956, with Dial Press in the United States and Michael Joseph in the UK. Though critics stumbled in their appraisal of its subject matter, the generally positive reception signaled that Baldwin could represent queerness and could render his private life public, to much acclaim.

Yet even as his professional life continued to ascend, Baldwin’s relationship with Happersberger encountered further obstacles. In 1955, after returning from a residency, Baldwin found that Lucien had befriended a jazz musician named Arnold. Baldwin took Arnold as a lover, which fractured the already tenuous relationship between Lucien and Baldwin. After Baldwin and Arnold traveled to Washington, DC, to see a staging of Baldwin’s play The Amen Corner, Lucien departed.

Baldwin’s career began to look brighter even as his personal life dimmed. Around the time he published Giovanni’s Room, he also published perhaps the finest American essay collection, Notes of a Native Son. Throughout the collection, Boggs writes, Baldwin deployed what became his signature essayistic technique: “oscillating between writing about Black Americans as part of a wider American ‘us’ and about a specific minority ‘we’ to point out the contradictions and failures of the American democratic ideal.” After the appearance of that generally well-received collection, Baldwin traveled to the South in 1957 to cover the civil rights movement, interviewing a student who had helped desegregate a high school as well as Martin Luther King Jr. The pieces further marked his ascent to the status of a well-known public intellectual. But having already alienated Lucien, Baldwin also lost Arnold. In 1956, Boggs reports, the musician told Baldwin “that he did not want to belong to him in any way.”

Baldwin found hope in a new beloved. In 1957, he met the Turkish actor Engin Cezzar, who had recently joined the Actors Studio. The two became, in their words, “blood brothers,” even as Cezzar dated a woman and did sex work when his budget tightened. After a racist attack hospitalized him, Cezzar left the United States in 1959 and returned to Istanbul, where he landed the role of Hamlet in a production that would continue for 200 performances. Baldwin planned to visit him there but delayed the trip because of, in his words, “money,” “personal hassles,” and “a very expensive item, sometimes called love,” which was another way of saying that he had found a new lover.

Something else was taking up Baldwin’s time at this point as well: politics—in particular, the struggle against segregation. In 1960, Baldwin returned to the South and became increasingly active as a spokesperson for the civil rights movement. In the course of writing several magazine articles, he met with student activists in the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), interviewed King again, and spoke in a Black church about, as he put it in a letter, being “the maid in this great, strange house, called America, and how the people who had played this role might be enabled to save it.” Baldwin’s time in the South further tied him to the nation that he had once sought to leave. In his inability to quit his homeland for artistic pursuits abroad, he came to feel a certain empathy for Cezzar: “I gather that what has happened to you in Turkey,” he wrote, “is analogous to what happens to me here, in relation, particularly, to Negroes here.”

But change was on the horizon. In 1961, Baldwin published Nobody Knows My Name, a collection of the essays he’d written when “my life in Europe was ending.” Including Baldwin’s civil rights reportage and an essay on William Faulkner, among other pieces, Nobody Knows My Name quickly became a bestseller. Its success came at a cost, though: When an overworked Baldwin finally showed up in Istanbul, Boggs writes, Cezzar inferred that the writer “was losing his health, losing his objectives, his motivations.” Thanks in part to the hospitality of Cezzar and his wife, the Turkish actor Gülriz Sururi, Baldwin recovered all of those things—and yet, unable to commit to settling in Istanbul, he became, as he put it, “a transatlantic commuter.” But unmooring himself provided newfound advantages. Distance from the United States offered Baldwin a new perspective on the country’s race relations, and his cross-cultural connection with Cezzar gave him a new belief in the possibility of interracial relations in America. Both, Boggs argues, provided Baldwin with the materials he needed to write his classic The Fire Next Time.

Composed of two letters, The Fire Next Time—perhaps Baldwin’s most famous book—offered a searing account of Jim Crow and the ongoing civil rights movement. In particular, it inverted the mainstream narrative of integration as requiring white people to accept Black people in their schools, workplaces, stores, and neighborhoods. “The really terrible thing,” Baldwin writes to his nephew early in the book, “is that you must accept them.” Following its publication, The Fire Next Time was on the bestseller list for 41 weeks. Baldwin’s interview requests exploded, and he received the George Polk Memorial Award for outstanding magazine reporting for the two pieces that made up the book. Though Baldwin was already an important novelist and wrote for many esteemed publications, The Fire Next Time propelled him to the height of his celebrity.

Baldwin continued his work in the civil rights movement—just before The Fire Next Time came out, he accompanied Medgar Evers to investigate a lynching in Mississippi—and he would use his heightened fame in the service of that agenda. When violence escalated in Birmingham, Alabama, in May of 1963, Baldwin cabled Robert F. Kennedy, blaming the federal government for enabling the violent opposition to desegregation. Alongside Lena Horne, Harry Belafonte, and others, Baldwin then met with Kennedy to discuss the civil rights movement. He also spoke at a rally for CORE and wrote an article about the struggle to end segregation. In August of that year, he even attended the March on Washington, though he was excluded from speaking, according to Malcolm X, because “they couldn’t make him go by the script…. Baldwin is liable to say anything.”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

In the tumult following Malcolm X’s assassination in 1965, Baldwin coped by throwing himself further into politics, then retreating to recover and write. In 1965, he participated with King in a voter registration march in Alabama, finished a short story collection, purchased a home for his mother, and fired Happersberger, who was then working as his business manager.

The two parted ways bitterly, but Baldwin did “what he always did,” Boggs notes: “transmute his psychological and emotional wounds into writing.” Baldwin returned to Cezzar’s care in Turkey and completed another novel, Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone. The following year, Huey Newton was jailed, Stokely Carmichael was placed under house arrest, and Baldwin’s former secretary, Tony Maynard, was charged with murder. After writing an op-ed defending Carmichael in 1968, Baldwin joined Betty Shabazz and Bobby Seale at a fundraiser for Newton and worked on Maynard’s defense. He also began a screenplay for a Malcolm X biopic, hoping to land his new crush, Billy Dee Williams, the leading role. Columbia Pictures had other suggestions: James Earl Jones, Sidney Poitier, and Charlton Heston in blackface.

But the violence of the 1960s was far from over. In 1968, amid nationwide street protests and police riots, Martin Luther King was assassinated. Baldwin had long held out hope for the United States, but King’s death appeared to be his breaking point: He sought escape and returned to Turkey in 1969 to stay at an apartment that Cezzar found for him. Yet even there, Baldwin could not escape his dejection. “With everybody dead or in jail or in exile or floundering in deeper political waters than they were meant to swim in,” he wrote to the poet Kay Boyle, “writing can seem, well, you know what writing can seem like.”

Thankfully, Cezzar and Gülriz helped as much as they could. The pair decided to produce John Herbert’s queer classic, the prison drama Fortune and Men’s Eyes, and recruited Baldwin to direct. Though he essentially spoke no Turkish, Baldwin was familiar with life in a cell and agreed to the project. As he wrote in the program notes, the play “ruthlessly conveys to us the effect of human institutions on human beings.” The play premiered in December with Cezzar as its star. The production was a hit, despite government repression. Baldwin was once again revived.

Back in France, he found more reason for hope in an old flame: the painter Yoran Cazac, whom Baldwin had first met in Paris through Delaney in 1959. (Delaney had developed feelings for Cazac, but Baldwin, according to the dancer Bernard Hassell, “snatched him up.”) When the two reconnected in Paris in 1971, Cazac already had a long-term partner whom he would marry the following year. That circumstance didn’t stop Baldwin: Though he eventually returned to his new home in Saint-Paul-de-Vence on the Riviera, he would be joined there by Cazac in the summer of 1972 after the latter left his pregnant partner. During the days, Baldwin drew on his experiences with the carceral state to write If Beale Street Could Talk while Cazac painted; at night, he read to Cazac from the manuscript. “Baldwin was creating another iteration of his lifelong dream,” Boggs writes, “of building a domestic and creative space with a male lover.” Though the two would become long-distance lovers after Cazac left to attend the birth of his son, Baldwin began referring to their relationship as a marriage.

Baldwin continued to be productive in these years, even though critics claimed that his literary abilities had declined. He collaborated with Ray Charles on The Life and Times of Ray Charles, which combined the singer’s music with dramatic scenes scripted by Baldwin and based on his story “Sonny’s Blues.” The play premiered in New York to negative reviews, a number of which were explicitly homophobic. In another sign of Baldwin’s waning cachet, Time magazine refused to run a piece about his meeting Josephine Baker in France because the editors thought both of them irrelevant. In 1974, critics offered mixed reviews of If Beale Street Could Talk, which Baldwin had dedicated to Cazac. Though Baldwin had been a celebrity throughout the previous decade, due in part to his involvement in the civil rights movement, the American press was now increasingly inclined to leave both him and the movement behind.

Still, Baldwin persisted. He’d begun work on a children’s book, Little Man, Little Man, at his nephew’s urging. He enlisted Delaney to illustrate it, but after Delaney’s mental health declined, Cazac took his place. Together, the two made progress on the book, a tale of three Harlem children navigating poverty and structural racism. The story’s serious subject matter was attributable in part to its semi-autobiographical nature. “I never had a childhood,” Baldwin once told a French journalist, “I was born dead.” He also applied his incisive eye to a book-length essay, The Devil Finds Work. In this scathing critique of Hollywood racism, Baldwin probed American race relations by reflecting on his experiences seeing films like 20,000 Years in Sing Sing and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner and, in general, found American cinema wanting.

Baldwin and Cazac’s relationship began to fall apart around the time they completed Little Man, Little Man. Afterward, they did not see each other again. Other old friendships and relationships came to an end as well. In 1979, Delaney died. As was his wont, Baldwin responded to the tragedy by returning to the written word. He worked on and published Just Above My Head, a portrait of a queer gospel singer who sees glimpses of Delaney on Paris’s streets, and The Evidence of Things Not Seen, a nonfiction book on the Atlanta child murders. He also worked on a play that addressed the AIDS epidemic, The Welcome Table, though he did not live to see it staged: On December 1, 1987, with his brother, Hassell, and Lucien Happersberger at his side, Baldwin died in France.

By organizing his biography around Baldwin’s intimate relationships, Boggs is able to shed new light on love’s centrality to Baldwin throughout his life. Of course, Baldwin has long been associated with love: He was publicly queer; most of his novels revolve around romance; and he regularly proclaimed the importance of love in his nonfiction. But Boggs uncovers the impact of these private loving relationships on the man, his words, and his politics. Delaney’s mentorship helped Baldwin start his career; Happersberger’s support helped him address queerness publicly in Giovanni’s Room; and Cezzar’s hospitality provided him the distance to see the United States anew—to say nothing of Baldwin’s other lovers and their many effects. Little wonder, then, that he considered love the key to solving American racism. As Boggs argues throughout the book, love had not only saved Baldwin from death; it had also expanded his notion of what life could be, providing hope for racial progress and a compass for his political vision.

In his discussion of the many people who helped make James Baldwin the author possible, Boggs reminds his readers that Baldwin’s works were collective productions. Where Baldwin often suggested that he was pregnant with his books, Boggs asserts that the other parents were Baldwin’s beloveds, to whom the books were often dedicated. And James Baldwin the public intellectual—as distinctive as his appearance, voice, and perceptiveness may have been—was no less collective. His advocacy for various political movements was thoroughly influenced by his relationships with others, whether people as famous as Martin Luther King or as obscure as Baldwin’s sixth-grade teacher (and member of the Communist Party USA), Bill Miller. Though Baldwin is regularly quoted regarding each new political moment, his insights belong as much to these people as to him.

This may be why Baldwin’s politics evolved to match the changing challenges of his times. Love was perhaps his guiding principle, but his political commitment pointed him in numerous directions. As a young man, Baldwin participated in socialist politics with Eugene Worth. Mid-career, he supported civil rights organizers like King and organizations like CORE and SNCC. Later, he advocated for Black Power organizers facing state repression, like Stokely Carmichael and Huey Newton. And he dialogued with—even if he sometimes disagreed with—Black feminists like Nikki Giovanni and Audre Lorde in the 1970s and ’80s. It was Baldwin’s openness to others—especially those younger than him—that made him always of the moment and prevented him from backsliding politically.

Love was hardly uncomplicated for Baldwin: In his life, it provided him with the means and ability to write but also pushed him to consider suicide. In his fiction, love was rife with pain, whether in the violence of a father in Go Tell It on the Mountain, the rejection of a brother in Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, or the difficulty of supporting a loved one behind bars in If Beale Street Could Talk. And in his politics, love led Baldwin to new concerns, even if these attachments resulted in feelings of dejection and despair when history thwarted his hopes. But it was this openness to others, fueled by love, that kept Baldwin hopeful and persistent even in his most pessimistic moments. For him, love was not just a compass but a renewable resource that kept him going throughout his life. And it is this same love that keeps his memory alive today, when people still turn to Baldwin to understand our new trying times, long after he has passed.

Donald Trump wants us to accept the current state of affairs without making a scene. He wants us to believe that if we resist, he will harass us, sue us, and cut funding for those we care about; he may sic ICE, the FBI, or the National Guard on us.

We’re sorry to disappoint, but the fact is this: The Nation won’t back down to an authoritarian regime. Not now, not ever.

Day after day, week after week, we will continue to publish truly independent journalism that exposes the Trump administration for what it is and develops ways to gum up its machinery of repression.

We do this through exceptional coverage of war and peace, the labor movement, the climate emergency, reproductive justice, AI, corruption, crypto, and much more.

Our award-winning writers, including Elie Mystal, Mohammed Mhawish, Chris Lehmann, Joan Walsh, John Nichols, Jeet Heer, Kate Wagner, Kaveh Akbar, John Ganz, Zephyr Teachout, Viet Thanh Nguyen, Kali Holloway, Gregg Gonsalves, Amy Littlefield, Michael T. Klare, and Dave Zirin, instigate ideas and fuel progressive movements across the country.

With no corporate interests or billionaire owners behind us, we need your help to fund this journalism. The most powerful way you can contribute is with a recurring donation that lets us know you’re behind us for the long fight ahead.

We need to add 100 new sustaining donors to The Nation this September. If you step up with a monthly contribution of $10 or more, you’ll receive a one-of-a-kind Nation pin to recognize your invaluable support for the free press.

Onward,

Katrina vanden Heuvel

Editor and Publisher, The Nation

What was it about Buckley that made him so attractive to liberals—and what was it about liberals that caused them to be attracted to conservative figures like Buckley in the first…

/

After a strange, controversial career, he has become one of the few figures who upholds the old rules of Hollywood—where the human body is the greatest special effect.

/