This piece is part of a joint CFR analysis assessing the geopolitical effect of the Trump administration’s tariffs policy on traditional U.S. allies, including Australia and New Zealand as well as Canada, the European Union, and Japan.

More From Our Experts

Joshua Kurlantzick is senior fellow for Southeast Asia and South Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations.

More on:

Australia and—to a lesser extent—New Zealand are central to U.S. defense strategy in the Western Pacific. U.S. strategy, which has remained consistent through the Presidents Joe Biden and Donald Trump administrations, aims to deter China’s expanding reach into the airspace and waters of the Pacific. This relies on building a network of partners in the region that allow operational access, possess sophisticated weapons, and are sites the Pentagon can count on to help deploy U.S. planes, ships, or ground forces in the event of a conflict.

Australia, along with Japan, is the most important of these defense partners in the Westen Pacific, and it has also been a dependable U.S. ally for many years. Since World War I, Australia has fought alongside the United States in every war it has entered.

Now, however, the Trump administration’s trade policy toward Canberra and Wellington has put the defense ties with two normally stalwart allies at risk, as both countries openly consider foreign policy shifts away from dependence on Washington.

More From Our Experts

In addition to trade’s economic effects, trade policy is threatening other key aspects of U.S.-Australia and U.S.-New Zealand relations: High-level intelligence sharing; strong support among policymakers and the general publics for ties to the United States; the continuation of a U.S.-led rules-based global order; and joint efforts to prevent Chinese influence from proliferating within democracies as well as in critical Pacific Island states.

Although Australia is one of the United States’ closest allies and a reliable economic partner (Canberra signed a free trade deal with Washington in 2005 and maintained a trade deficit of nearly $27 billion last year), Trump still hit the country with a 10 percent tariff. Australian policymakers, and the broader public, were further angered by public comments by U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer shortly after the tariffs went into effect. He told the Senate Finance Committee that despite the U.S. surplus with Australia, the United States still has a massive deficit worldwide and “should be running up the score on Australia” to help cut that number.

More on:

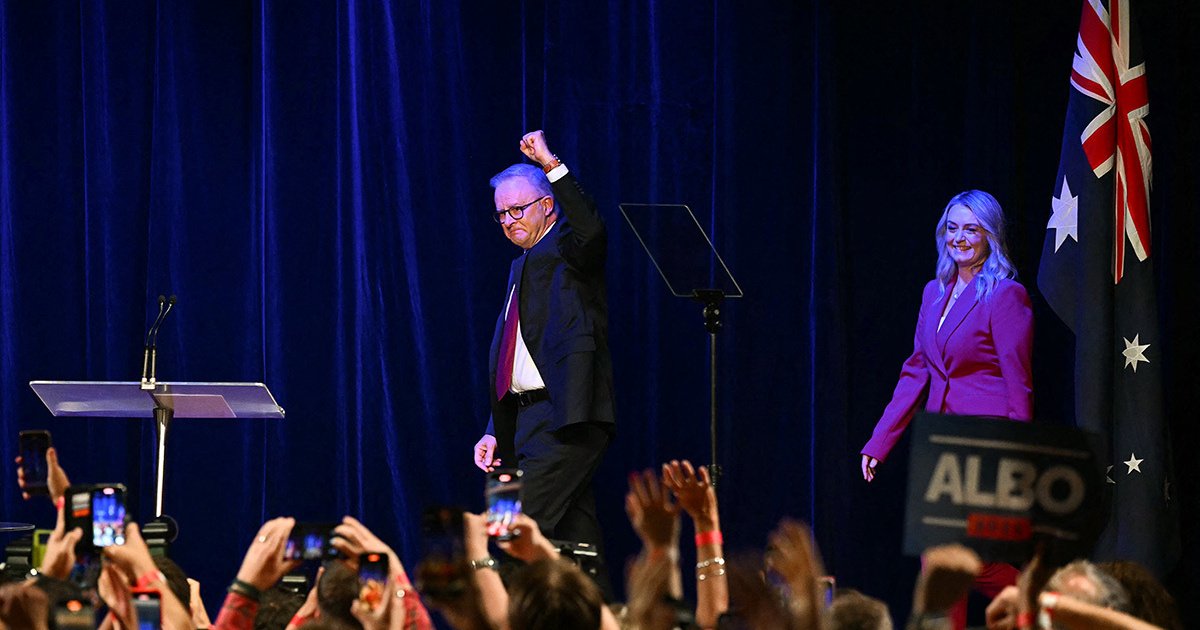

Comments like these have had tremendous fallout in Australian domestic politics, even though the tariffs’ economic effect on Australia is fairly modest. A recent report from the Productivity Commission, the Australian government’s independent research and advisory body, noted that the country is in “probably the best position” globally to deal with the new tariffs. Still, the Trump administration’s regular criticism of Australia and its disdain of international institutions helped the Australian Labor Party—which had not previously enjoyed much popularity—win re-election in May. It did so largely because it positioned itself as the party best able to combat the White House.

Indeed, the White House’s public stance toward Australia, as well as Australian fears that the U.S. is no longer a reliable partner, has made the United States widely unpopular in Australia. A Pew study in May of foreign countries’ views of the United States found that 71 percent of Australians have an unfavorable view of its longtime ally—one of the highest levels of U.S. unpopularity among all the countries surveyed.

Polling and interviews tell a similar story in New Zealand, which was hit with a 15 percent tariff. The fact that New Zealand, a robust free trader that held a tiny trade surplus with America, received an even higher tariff than Australia without an apparent reason has befuddled and angered New Zealand policymakers and the public. Only about 9 percent of New Zealanders think Trump 2.0 has been a net positive for New Zealand, and those negative views cut across every party.

This level of public animosity will make it harder for the United States to achieve any of its aims with Australia and New Zealand. In both countries, the apparent unreliability of Trump’s White House and its desire to punish its allies has led to calls from Canberra and Wellington for more “independent” foreign policies relying on a broader range of partners in Asia and Europe. New Zealand in recent years had even drawn closer to the United States, but that decision is now under serious review by politicians from multiple parties.

Beyond rhetoric, the shift in perception of the United States affects security on the ground. Even as the United States reexamines the massive U.S.-Australia-United Kingdom (AUKUS) nuclear submarine deal and calls on Australia to boost defense spending, the belief in Australia that AUKUS will actually come to fruition is dwindling. Many Australians even oppose the deal now since they do not trust Washington to pursue a responsible foreign policy. A new poll by the Lowy Institute found that “only 36 percent of Australians expressed any level of trust in the United States to act responsibly in the world.”

Killing AUKUS would be a massive mistake because it stands to benefit both Washington and Canberra. As Jennnifer Parker of Australian National University notes, the deal “secures access to Southeast and Northeast Asia from a location beyond the range of most Chinese missiles, adds a fourth maintenance site for Virginia-class submarines, and delivers a [U.S] ally with an independent nuclear-powered submarine industrial base.”

Mistrust of this White House, and its approach toward America’s intelligence agencies, is also impeding intelligence cooperation with Australia as well as New Zealand. The two allies are members of the intelligence alliance Five Eyes, along with the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. This is normally one of the closest intelligence-sharing agreements in the world, but the U.S. Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard has increasingly refused to share information with Five Eyes partners on important topics, including updates on Russia-Ukraine peace talks. This has caused Wellington and Canberra’s mistrust of the Trump administration to grow, meaning both countries are holding back information as well, according to their officials.

Such intelligence is essential to the United States’ monitoring of Chinese activities not only in Southeast Asia but also in the Pacific Islands. There, China has been extremely assertive in cultivating influence. At the same time, Australia and New Zealand have ramped up their engagement with the Pacific. Australia remains the single largest aid donor to the Pacific by a considerable margin. In recent years, Canberra has made several deals with Pacific Island countries that combine aid with provisions to ensure the Australian government is consulted on security matters. Without Australian and New Zealand intelligence-sharing on China’s activities in the Pacific, the United States will be left partly blind to Beijing’s actions in a critical theater.

Australia and New Zealand were also two of the first major democracies to deal with Chinese influence inside their own local and national political systems. They have seen their leading business, education, and intelligence institutions as well as Chinese diaspora organizations affected. These two countries’ experience, and their responses, have acted as models to counter Chinese influence tactics.

Today, leading democracies across the world—including the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, France, and Japan—are facing such influence tactics within their own borders. Increasingly alienated from Australia and New Zealand, U.S. intelligence will not benefit from their deep well of knowledge about these Chinese tactics, either. As with the other geopolitical effects of Trump’s tariffs, it will likely only become more difficult to reverse the fallout of these policy decisions on the United States’ relations with its closest allies.

This work represents the views and opinions solely of the author. The Council on Foreign Relations is an independent, nonpartisan membership organization, think tank, and publisher, and takes no institutional positions on matters of policy.