While ski gear has not escaped the wrath of tariffs, unless something, changes, companies expect the real pain to arrive next season.

(Photo: Courtesy of Moment Skis)

Updated September 10, 2025 08:46PM

Ski prices are set to rise this winter, and tariffs are to blame. Or, depending on where you sit, the fact that most skis aren’t made in America is.

On August 1, President Donald Trump imposed new tariffs on imports from around the world, including from Asia and Europe, where most skis and almost all ski-specific components—like edges—come from, driving up the cost of both getting skis to the U.S., and making them here.

As of the time of publication, the Trump administration had settled on a 15 percent tariff on European goods, jumping to 50 percent on steel and aluminum (key materials in skis), and a 30 percent tariff on Chinese goods, suspended until November, when it could jump to 145 percent.

Most ski manufacturing takes places in Europe and Asia, where the factories and processes have been scaled to produce larger volumes. (Photo by JOE KLAMAR/AFP via Getty Images)

Most ski manufacturing takes places in Europe and Asia, where the factories and processes have been scaled to produce larger volumes. (Photo by JOE KLAMAR/AFP via Getty Images)

For the ski business, there are several conundrums here. First, skis are full of mixed materials, so the tariffs are hard to figure out based on a ski’s construction, and the specific provenance of those materials. Next, the new costs have retroactively added extra expense to orders already signed at pre-agreed prices by retailers across the U.S. for the 2025-’26 season.

Who, then, will absorb these costs? Manufacturers, wholesalers, retailers, or the consumer? And moreover, what will those costs be?

“This year will be weird because some inventory made it through tariff-free, when other products didn’t,” says Gary Fleming, president of Winter Sports Retailers (WSR), and a director of the National Ski and Snowboarders Retail Association. “But ultimately it lands with the consumer.”

WSR represents over 240 retailers that Fleming calls “mom-and-pop shops.” He says their members were stunned when brands came back to them midsummer with new prices on orders that had already been booked in March—what’s usually considered the end of the “sell-in” season. “Very few retailers adjusted orders because it was overwhelming,” Fleming explains, “but the margins for retailers have not changed.”

What that means is a higher sticker price by the time any tariffed ski hits a retail floor. Fleming notes that an extra fee most anywhere in the supply chain flows downstream and compounds. “Everybody takes a margin at every step, you know: the manufacturers need a margin, the distributor needs a margin, the retailer needs a margin.”

The trick is where that extra cost shows up in the supply chain, and how many steps there are in that particular chain. Some brands are vertically integrated and own their own factories and distributors, others aren’t. Some brands are direct to customer (D2C), but by and large the ski business relies on specialty retailers.

K2’s skis have been manufactured in China since the early 2000s. (Photo: Courtesy of K2 Skis)

K2’s skis have been manufactured in China since the early 2000s. (Photo: Courtesy of K2 Skis)

“Based on what we know today, our 2025 average duty rate across the portfolio will be about 20 percent,” says Josee Larocque, CEO of Elevate Outdoor Collective, the parent company of K2, Völkl, Line, and other brands. “Realistically, [that extra cost] is shared between … us, our retail partners, and the consumer. We’re doing everything we can to minimize the impact on skiers.”

Larocque says that 45 percent of Elevate’s business is in the U.S., and they won’t be spreading the impact of those tariffs to other markets like Canada and Europe. But, like most brands, the full shape of those added expenses remains unclear. Duty is only imposed once a ski reaches U.S. shores, and tariff rates have been changing so frequently, up until recently, that the final prices of skis were fluctuating even while they were in transit.

Most brands rushed to get skis on shore before August 1, and many succeeded; there is also a good amount of carry-over stock from last season (ski models that haven’t changed) already on shelves. But next season, nothing will have escaped the extra duties, says Fleming. “That’s when you’re going to see big increases.”

Not all of that can be pinned on tariffs, though. Josh Malczyk is the North American marketing director for Elevate Outdoor Collective, and notes that, with the exception of the bump all recreation industries got during the pandemic—which has since flattened back out—skier participation and ski sales haven’t significantly grown on this continent for the better part of a decade. (Research from Snowsports Industries America backs this up.) Because of this, even with rampant inflation, we haven’t seen ski prices noticeably increase for a long time, and brands had been looking for a window to catch up on that long before global trade blew up.

“Costs in general have been going up for a long time in the snowsports industry as a whole,” Malczyk explains. “I think it has done itself a disservice by having such small margins and not anticipating things like this. There’s been a $599 ski for the last 25 years. I mean, where else have prices been the same for that long on something? So it’s like, damn, we should be incrementally raising a little bit each year. But, you know, there are certain price points that our consumers come to expect. And so there’s a bit of sticker shock here.”

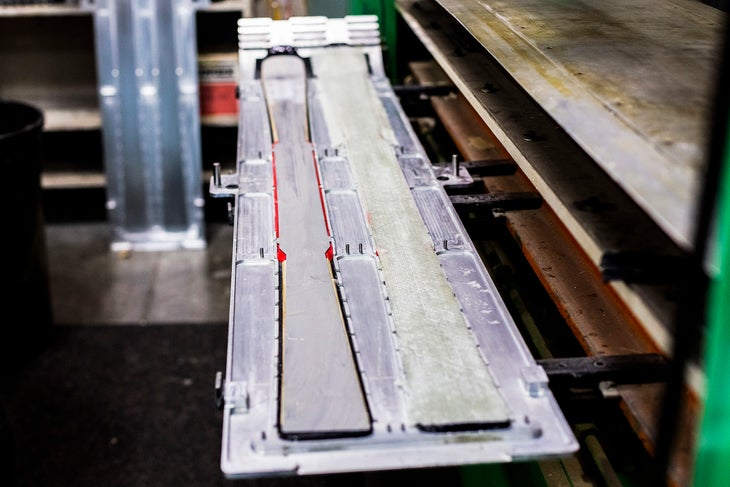

Moment Skis are made in the company’s Salt Lake City factory. (Photo: Courtesy of Moment Skis)

Moment Skis are made in the company’s Salt Lake City factory. (Photo: Courtesy of Moment Skis)

Fleming, for his part, is hopeful that those price increases won’t hurt consumer confidence, as he’s seeing it translate into an average of about a $50-increase per pair of skis this season. “My guess is I don’t think going from $699 to $749 is going to stop somebody from buying it,” he says.

Both Fleming and Malczyk believe the bigger difficulty is administering the new regime, which ultimately also adds cost. Brands will make a declaration of what percentage of materials are in which skis, and they will try to anticipate the duty. But in the end, there won’t be a single net tariff rate they’re dealing with, it will be different for every single product. Trying to stay on top of this in itself as an administrative task will add work, and more expense.

There’s also a huge amount of uncertainty around whether tariff rates will remain steady or continue to shift, as they’ve done over the last six months. New trade deals are in negotiation around the world, like the U.S.-Canada-Mexico agreement, which is scheduled for review in July 2026.

“We’d prefer not to have to go through something like this with any sort of frequency,” says Laroque. “We have enough unpredictable factors to deal with in the winter business.”

Indeed, few industries in the world pin themselves to a four-month sales season so heavily influenced by weather. If it doesn’t snow, especially before Christmas, the ski industry already takes big hits. Having one other thing outside of its control is especially difficult.

Of course for some the answer will be simple: re-shore ski manufacturing in the U.S. But the trick with that verbiage, at least, is there’s nothing to bring back, in this case. The industry has always been overseas, mostly in Europe—where the majority of it still is—and has also spread to Asia over the last 20 years.

“It’s too early to tell if U.S.-based brands, specifically, will see a boost in re-orders for this season, and we have not heard about any re-shoring efforts at this point,” says Nick Sargent, president of Snowsports Industries America, the leading industry advocacy group. “Re-shoring U.S. ski production is incredibly complicated. A number of companies are already building great, high-quality skis and snowboards here in the U.S., but to make them at the quantity coming from our suppliers in Europe, it’s not something that can be done quickly. The factories that have been building skis for decades have a legacy of high-quality mass production. Further, labor costs in the U.S. … are vastly different and would impact the cost of production. The tariffs won’t change that.”

Sargent says European factories in general have more scale and are highly automated, which is not an easy thing to shift stateside. There are roughly 20 times more skier visits in Europe than in the U.S annually, and the retail market is about three times as big there, according to most estimates. This gives Europe commanding authority over global ski production.

“You can’t move ski presses and your entire development pipeline when you own, you know, I think three or four factories,” Malczyk adds. “Those are large manufacturing facilities that require funding and volume. … When you own the factory, you own the distribution to the sales, so you have more control over things. But you also have more risk because you can’t negotiate with the factory very much because you own the damn thing.”

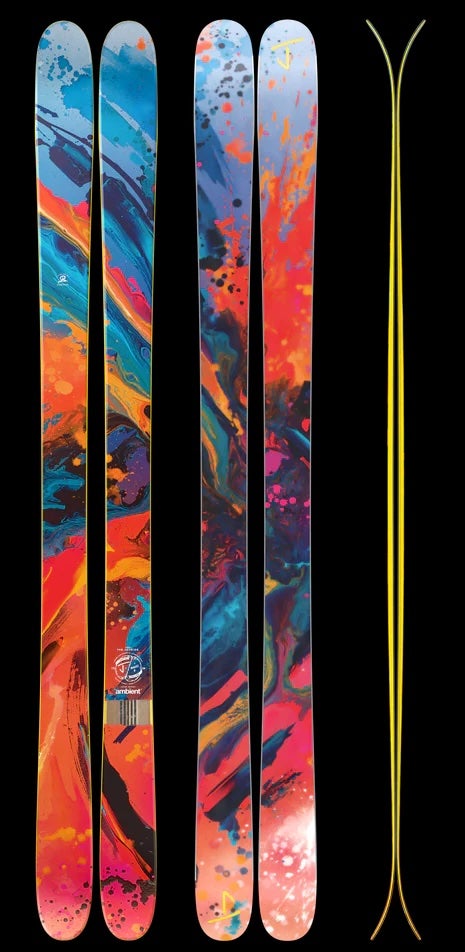

J Skis are made across the border in Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of J Skis)

J Skis are made across the border in Canada. (Photo: Courtesy of J Skis)

There are only a small handful of ski factories in the continental U.S., mostly working at a boutique scale. The largest ski factory in North America is in fact in Rimouski, Quebec—on the other side of the border. Utopie MFG has been building skis for Jason Levinthal since he launched his Burlington, Vermont-based brand, J Skis, in 2013. It’s less than an eight-hour drive from his house to the factory, but 90 percent of the skis he sells will come back to the U.S., which means his products will be tariffed.

“I’ve been proud for the last 11-plus years to be making my skis—what I consider to be—locally. Because I can drive to the factory. It just happens to be over a border into Canada,” Levinthal says.

Levinthal explains Utopie MFG just expanded, is extremely advanced, and is doing a great job for him. For this reason alone he doesn’t want to move production. But even if he wanted to, options are limited.

“I can tell you on this side of the border, there’s nowhere I can make [skis]. Like, I don’t have an option to make them somewhere else. Not in the Northeast. Maybe I could ask Never Summer [Snowboards] to also make our skis, but they didn’t have capacity when I started doing this.”

That would also mean a 1,900-mile distance to Denver, Colorado, whenever he needs to visit the factory, as opposed to 700 miles. But the bigger issue is it’s not possible to move proprietary manufacturing that easily, even if someone did have space.

“Working with a factory is a deep relationship,” Levinthal insists. “A very deep relationship. It’s not like ordering pizza. It’s just not that. I think everyone learned what supply chain means during the pandemic. That’s still a real thing. You can’t just change your supply. The supply chain takes months—many months, sometimes over a year—to get the product from a purchase order to your hands.”

As far as what that means for the consumer, for the short term at least, American-made skis won’t be any cheaper. Not the least because major brands won’t be rushing to move production, but also because shored production is still facing challenges from tariffs.

Skis fresh off the conveyor belt at Atomic’s Austria GmbH factory in Altenmarkt im Pongau, Austria. (Photo: Joe Klamar/AFP)

Skis fresh off the conveyor belt at Atomic’s Austria GmbH factory in Altenmarkt im Pongau, Austria. (Photo: Joe Klamar/AFP)

Luke Jacobson is the CEO of Moment Skis, the largest U.S. ski maker thanks also to a recent expansion (which still doesn’t equal Utopie MFG). But even he says economies of scale mean things like edges, bases, top sheets, and even Titanal (an aluminum alloy that bonds with epoxy used only by the ski and aircraft industries) will continue to be made in Europe for the foreseeable future, because that’s where most of the demand will be.

“The materials that I’m buying now from Europe—edge is a different one because there’s different steel and aluminum tariffs that make that dramatically more expensive—but on the plastic side of things like the topsheets, bases, sidewalls, the the rubber damping that goes in tips, those items are costing almost 30 percent more than what they cost in January [of 2025].”

Jacobson says the impact the tariffs have had on the U.S. dollar, weakening it against the Euro, have also added more expense. As to whether taking on extra manufacturing work domestically could compensate for that, at the moment the answer is no.

“When we bought our new facility three years ago, we had so many people reach out to us … but it’s not major players,” he explains. “[Lately we’ve] had a lot of different brands reach out asking if we have capacity to build their products, but we haven’t got a lot of extra interest just because of the tariffs.”

OEM manufacturing, or producing for other brands, was never part of Moment’s business plan; their expansion was purely to make their own skis and sell more. That plan’s still on track, but it’s messy now, just like it is for most brands. Moment had a lot of materials already in-house when they began building last March, but just like J Skis, that’s only skirting the full impact of tariffs in the short term.

“We’re going to hold our prices for now,” Levinthal says. “But we still are going to get another quarter of our skis shipped in September and October, and we don’t know what the cost will be.”

Holding prices was only possible because J Skis downsized staff and made other cuts, and they were fortunate to get most of their season’s order before August 1. “I feel lucky, and I’m passing that onto my customers,” says Levinthal. “But I may have to raise prices if [costs] go up to a point where it’s financially unsustainable for me.”

When asked if there might be any benefit to a more insulated marketplace for American products, Moment’s Jacobson says he could see potential for European brands bringing less inventory into the U.S., but he’ll have to wait and see if that equals anything extra as far as ski sales for Moment.

As for the bigger brands, like K2, Line, and Völkl, they’ve also been cutting internal costs as much as they can to try to shield consumers. But for the foreseeable future, there’s no real workaround to having to hike prices at the retail point.

“We have a full prototyping facility called the Arc here in Des Moines, where we can make small runs of skis and boards,” Malczyk says. But in no way can we shift our volume to America in six months when you don’t even know what’s going to change. Forty percent of our stuff is made in Asia. … We don’t have lobbyists in Washington that can deal and get us a reprieve, like Apple with the iPhone.”

In terms of an industry wide effort in that regard, Sargent says, there isn’t really any capacity at the moment.

“In the short term, we need to mitigate the tariffs,” he says. “And when the time is right, use our industry’s economic strength to try to gain exemptions or reduced tariffs.”