How Ukraine and its partners are tackling a human-capital crisis.

“The full-scale invasion has closed the Ukrainian sky. And international bus drivers are among those who keep families and friendships together, and influence hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians’ lives,” said Yulia, a Ukrainian woman who had recently completed a course to help her obtain a bus driver’s license, and now works for an international transportation company.

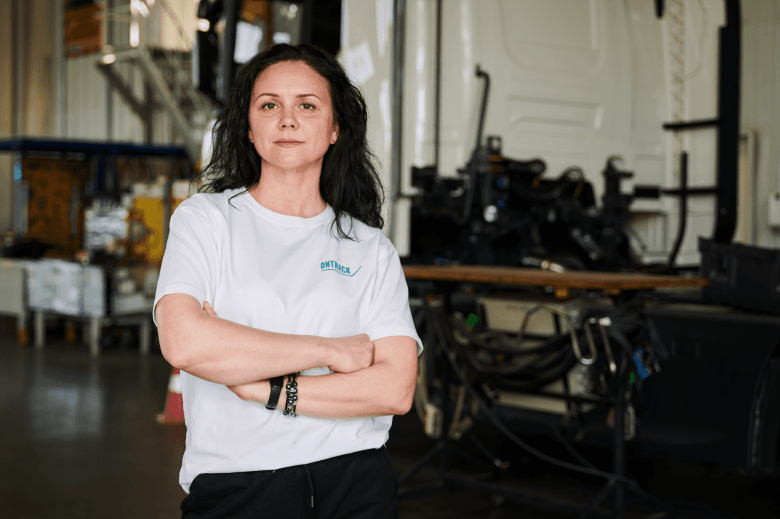

Yulia’s is one of the success stories featured on the website of Reskilling Ukraine, a Swedish nonprofit that provides free professional training to Ukrainian women and veterans. The initiative addresses a human capital crisis driven by destruction, displacement, and massive loss of population since Russia launched its all-out attack in February 2022.

Getting the Wheels Turning

Reskilling Ukraine rolled out its first training program for women, OnTrack, in 2023. Participants can obtain commercial licenses to drive trucks and buses, operate construction equipment, work as mechanics, or install solar plants. Funding comes mainly from the Swedish government, and the organization is an offshoot of Beredskapslyftet, a larger Swedish nonprofit.

“After understanding and doing some research in Ukraine, we saw that there is a huge demand for new professionals within some industries,” said Viktoria Posieva, the organization’s media contact.

Transportation and logistics are such industries – impacted both by the war and by the legacy of longstanding gender-based legislation and stereotypes. Until 2017, a Soviet-era mandate barred women from around 450 professions in Ukraine. While the World Bank and other partners have worked on “lifting legal barriers” especially in “sectors that had the highest number of bans, such as transport and logistics,” women still face “soft” barriers to entry into these fields, according to the bank.

“We had some driving schools that said, ‘Okay, this [initiative] is not for us because we don’t think women should drive big trucks,’ ” Posieva said. “But when it comes to now it’s all smooth because people see the results.”

More than 100 women trained by the organization now work as truck or bus drivers, embarking on expeditions through Ukraine and surrounding countries.

“The average age of our graduates is 42, so it’s middle-aged women,” said Posieva. “Typically, they are married. They have, for example, a husband serving in the military, or they served in the military before. They’re internally displaced. So they see this as an opportunity to be on their own, to be on the road, to do something important for the country.”

The jobs often come with more financial security than other work. “In Ukraine, you can earn more as a truck driver than a school teacher,” Posieva added.

For some, the program offers clarity, even if the road leads elsewhere. “Sometimes we have women who have high motivations and they go into the [training] and they understand, ‘No, it’s not for me.’”

Ukraine’s freight transportation market is short around 40,000 drivers, leaving 30% of trucks idle, Deputy Minister of Communities and Territories Serhiy Derkach told Ukrinform in July. The passenger transportation market is similarly facing a shortage of 6,000 workers.

The ministry’s own response to this issue was a project called She Drives, training women for careers in either passenger transportation or trucking with courses to obtain class D or class C/CE licenses.

The training course for trucking faced an uncertain fate in January 2025 when USAID funding was cut. About 20% of the 100 participants were left stranded with incomplete training, according to the She Drives team. The initiative was reinstated after United Nations Women stepped in and reallocated funds along with international partners, and the women were able to obtain licenses.

As of August 2025, 11 graduates are employed in the passenger transport sector, an industry that has only around 1% women employees to date, according to the She Drives team. The program now offers Code 95 Certification, allowing for service throughout the EU in addition to Ukraine.

In 2025, Reskilling Ukraine expanded with the launch of Unit 6.0, a new program dedicated to veterans. It currently offers two training courses: one to become a solar plant installer and another to become a career counselor for fellow veterans.

The veterans’ course teaches the foundations for a career helping former soldiers reenter the job market: expertise in analyzing the labor market, working with clients, and providing advice on building a resume. The subsequent practical component allows each student to gain experience through an internship at a company.

Though still in its early stages, the initiative has already made an impact, says the organization.

Posieva shared the story of a former English teacher from western Ukraine who joined the military after the full-scale invasion. “When he came back, he went through our education [program] to become a career consultant after he was advised by his wife,” she said.

Following the training, he completed an internship at an international electronics company with operations in Ukraine.

“After this internship, he got a job as a chief veteran’s officer in a factory. It was a huge success for us.” Those in such positions help private companies find talent returning from the front lines, and provide a support network for veterans within the company.

That helps veterans transition to civilian careers, but are also valuable for another reason. “Veteran’s officers can connect and can talk to those actively serving in the military so [the soldiers] can feel connected to their previous workplaces and colleagues,” said Posieva. So far, 36 veterans have undergone training with Unit 6.0.

A government poll of veterans found that just 2.9% of Ukraine’s 1.2 to 1.3 million veterans have received any form of reskilling support, according to Oleg Shymanski, Ukraine’s deputy minister for veteran affairs. “We need to work with veterans while they are still in the military,” Shymanski said at July’s 2025 Ukraine Recovery Conference. Unit 6.0’s graduates will be among those helping to build channels for veterans to find work after service.

Reskilling Ukraine’s in-person training courses are held both in Kyiv and the Ternopil region in western Ukraine. But for many, the capital is no longer a viable option. “A lot of candidates say, ‘Can I please travel to the western part?’ because they know that the western part is safer than Kyiv,” said Posieva. “And now, sometimes candidates just refuse to go to Kyiv, because of heavy bombing every week.”

To navigate these risks, the organization has implemented safety protocols for when the air raid sirens sound, although as Posieva noted, “I’m Ukrainian myself, and we all know what to do.”

The Big Picture

Tackling endemic corruption and embracing a private-sector-led economy are key for Ukraine to catch up to EU members in economic performance, according to World Bank Managing Director of Operations Anna Bjerde, speaking, like Shymanski at the 2025 Ukraine Recovery Conference.

Bjerde stressed that major challenges will need to be overcome along this road. “First is the destruction of capital and acute labor shortages that constrain growth.”

The lack of both skilled and unskilled labor has hobbled the economy since independence in 1991 as millions have emigrated either seasonally or permanently for jobs, many going to Central Europe or further west. The war multiplied these losses many times over: 3.7 million internally displaced people, 6.9 million abroad, and around 1 million active military personnel, according to the International Organization for Migration.

Deputy Prime Minister Oleksei Chernishov has also underscored the human side of this challenge: “human capital is the primary source that activates both financial and technological capital, especially in times of crisis.”

Reskilling Ukraine and She Drives are working beside other employment efforts from the EU; the United Nations Development Program; and International Organization for Migration. The mission is about more than filling vacancies – it’s about offering purpose and resilience for the individuals who are rebuilding Ukraine amid war.

William Kirkiles was an intern this summer at Transitions. He is entering his sophomore year at Brown University.

Photos, except top image, are courtesy of Reskilling Ukraine.