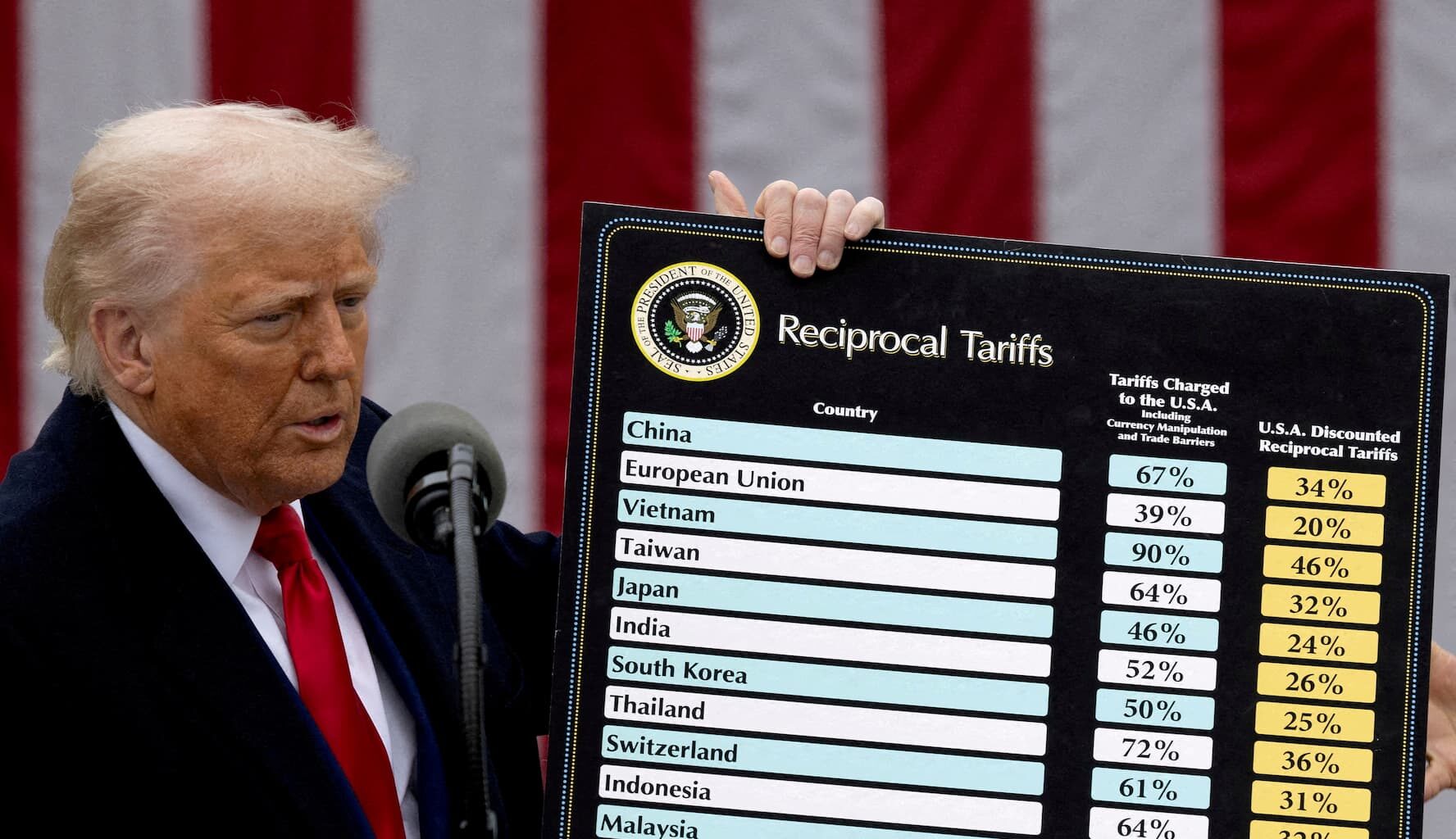

On April 2, 2025, President Donald Trump declared that foreign trade and economic practices had created a “national emergency.” Large and persistent annual U.S. trade deficits, he said, had “hollowed out our manufacturing base,” discouraged the creation of “advanced domestic manufacturing,” undermined “critical supply chains,” and rendered the U.S. defense industrial base “dependent on foreign adversaries.” To meet this emergency, he invoked his authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) to impose a 10% tariff on all countries and an individualized higher tariff on countries with which the United States has the largest trade deficits in goods.

Does IEEPA provide an adequate legal basis for the president’s actions, which have affected the United States’ economic and diplomatic relations with nearly every country on earth? The federal judiciary is now addressing this question.

A challenge to Trump’s executive order from U.S. firms and jurisdictions has moved quickly through the courts. On Sept. 9, the Supreme Court not only agreed to hear the case but also put it on a fast track. The government must file its brief by Sept. 19, challengers must reply by Oct. 20, and the Court will hear oral arguments during the first week of November. The Court may hand down its decision, which could undermine the centerpiece of the president’s economic agenda, by year’s end.

As the United States entered World War I, Congress passed the Trading with the Enemy Act (TWEA) in 1917. This statute gave the executive “an extraordinary degree of control over international trade, investment, migration, and communications between the United States and its enemies.”1

Over the next six decades, presidents steadily expanded their interpretation and use of TWEA. Early in his first term, President Roosevelt invoked it as the basis for declaring his Bank Holiday. Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson used it to deal with a wide range of trade, investment, and currency issues. President Nixon invoked it to declare a state of emergency and impose a 10% supplemental tariff on all goods entering the United States, an action that figures centrally in the current debate about President Trump’s policies.

In the wake of Vietnam, Watergate, and revelations of domestic spying, Congress became increasingly concerned about the expansion of executive power and sought to rein it in, in part by reevaluating its grants of emergency power to the president. Among other statutes, TWEA was criticized for the open-ended authority it gave the chief executive. Specifically, a House report on the reform of emergency legislation charged that TWEA required no consultation with Congress, set no time limits on a state of emergency, provided no mechanism for congressional review, gave Congress no way of terminating it, imposed no effective limits on the scope of economic powers the president could use, and failed to require a relationship between the nature of the emergency the president declared and the actions he took pursuant to this declaration.

To correct what it saw as these deficiencies, Congress proceeded in two steps. First, in 1976, it enacted the National Emergencies Act (NEA), an umbrella act covering all emergencies. It imposed new reporting requirements on the president, created mechanisms for the termination of emergencies, and provided for the termination of all existing emergencies, except those imposed pursuant to TWEA. Second, to address TWEA, which raised complex issues of monetary and foreign policy, Congress enacted IEEPA in 1977 to limit the authorities the president could invoke and subject the president to a range of procedural limitations, including those imposed by the NEA.

In an important move, the report of the House Committee on International Relations, a detailed document that undergirded this reform effort, declared that “emergencies are by their nature rare and brief, and are not to be equated with normal ongoing problems,” adding that “A national emergency should be declared and emergency authorities employed only with respect to a specific set of circumstances which constitute a real emergency, and for no other purpose.”2 To put this in medical terms, the House sought to distinguish between the ailments that lead patients to consult their internist and the unusual, sometimes life-threatening events that make them rush to the ER.

IEEPA was designed for the latter, not the former. Consistent with the language of the House report, the text of the Act states that the presidential authorities it creates “may only be exercised to deal with an unusual and extraordinary threat with respect to which a national emergency has been declared.”3

Many analysts believe that IEEPA has failed to achieve one of its most fundamental objectives—limiting executive power.4 Not only have the justifications for invoking the statute become less geographically specific, but also the stated rationales have become broader in both length and subject matter. Far from being “rare and brief,” as the House intended, IEEPA-based emergency declarations have become numerous and long-lasting. Presidents have invoked IEEPA more than 70 times; on average, these emergencies last for nearly nine years, and many remain in place for decades.

The mechanism for terminating emergencies has failed, in part for reasons that the drafters of IEEPA could not have anticipated. The bill provided that Congress could end an emergency by passing a “concurrent resolution” to this effect in both the House and Senate. This meant that a simple majority in both chambers would suffice, and the president would have no say in the matter.

But just six years after the passage of IEEPA, in the case of INS v. Chadha (1983)5, the Supreme Court ruled that this device, known as the “legislative veto,” was unconstitutional. In response, Congress revised a number of statutes, including those dealing with economic emergencies, to require concurrence from both Houses, subjecting this “joint” resolution to a presidential signature or veto.6 If the president rejected the resolution, it would then require a two-thirds majority in both congressional chambers to override his veto and put the resolution into effect—a threshold that is especially hard to clear in an era of heightened partisan polarization and narrow legislative majorities. It is not surprising that Congress has never been able to terminate an emergency declaration based on IEEPA.7 For all practical purposes, then, the president gets his way on this matter—unless the judiciary intervenes.

This brings us to the current controversy sparked by President Trump’s invocation of IEEPA as the basis for his new tariff regime. In response, companies claiming harm resulting from the president’s action filed suit alleging that he had exceeded his legal authority under IEEPA. On May 28, 2025, the United States Court of International Trade (CIT) ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. The question, the court stated, is whether IEEPA gives the president the authority to “impose unlimited tariffs on goods from nearly every country in the world.” The answer was that it did not, and the court set aside all the tariffs President Trump had imposed under the authority of this Act.8

In finding for the plaintiffs, the Court of International Trade took note of the fact that in U.S. v. Yoshida (1975), the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals had upheld President Nixon’s authority under TWEA to impose a 10% tariff to counter a balance of payments crisis.9 Because IEEPA had repeated, verbatim, the relevant portion of TWEA, the Trump administration’s lawyers argued that this 50-year-old case was relevant to, and justified, the president’s action.10

The Court of International Trade disagreed, citing the court’s language in Yoshida: “The declaration of a national emergency is not a talisman enabling the President to rewrite the tariff schedules.” The Yoshida court had upheld President Nixon’s tariffs on the basis that they were limited in both extent and duration, “which is quite different from imposing whatever tariff rates he deems desirable.”11

Similarly, the Court of International Trade declined to read the president’s power under IEEPA to “regulate . . . importation” as authorizing the president to “impose whatever tariff rates he deems desirable.” This is not only an issue of statutory interpretation, said the Court. Reading the statute to give the president unlimited discretion over tariff rates “would create an unconstitutional delegation of power.” Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution gives Congress the authority to impose tariffs. While Congress may delegate a portion of this power by allowing the president to execute it, it cannot give away this power altogether without breaching constitutional limits. After all, as James Madison wrote in Federalist 48, “the powers properly belonging to one of the departments ought not to be directly and completely administered by either of the other departments.” (My emphasis.)12

The Court also cited, and endorsed, the plaintiffs’ use of another, much more recent principle: The Supreme Court’s “major questions” doctrine, which states that when Congress delegates powers of “vast economic and political significance,” it must “speak clearly.”13 Regarding tariffs, Congress had not done so. Indeed, the long list of presidential powers in IEEPA did not include the words “tariffs” or “duties.”

The Trump administration appealed this decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, which opted to hear it before an en banc panel of all of its active judges in lieu of the normal three-judge panel. During oral argument on July 31, Justice Department lawyer Brett Shumate argued that IEEPA is written broadly, and the power to impose tariffs is included under the power the Act grants the president to “regulate” imports. But as one analysis put it, the judges on the federal appeals court weren’t buying it. “Why would we read tariffs into that statute?” one judge asked. “Is the plain meaning of ‘regulate’ to impose tariffs?” another inquired. As for the administration’s use of the Nixon-era case to justify a broad and open-ended tariff regime, one judge told Mr. Shumate, “[Y]ou are just discarding portions of Yoshida that you don’t like.”14

On Aug. 29, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit handed down its decision reviewing the holding of the CIT. By a majority of 7-4, the appeals court upheld the core of the CIT decision: In imposing his sweeping program of global tariffs, President Trump had exceeded the authority granted to him under IEEPA. Because the majority decision, the concurring opinion, and the dissent offer a roadmap to the arguments the Supreme Court will eventually hear, I lay them out at some length.

In its majority decision, the appeals court noted that the enumeration of powers delegated to the president did not “explicitly include the power to impose tariffs, duties, or the like, or the power to tax.” Many statutes do give the president the power to impose tariffs, and in each case, Congress has used “clear and precise terms” to do so. Accordingly, the appeals court rejected the government’s assertion that the president’s power under IEEPA to “regulate” implied the power to impose tariffs, and it provided examples where Congress had granted to the executive branch the power to regulate without delegating the power to impose tariffs.15

In addition to arguments based on the language of the statute, the majority invoked the Supreme Court’s “major questions” test to reject the government’s claims. This test becomes relevant whenever the government infers from statutory language an authority, not explicitly granted, that entails vast “economic and political significance.” In recent years, the Supreme Court has deployed this doctrine to restrict the executive branch’s authority in areas such as the EPA’s environmental regulation and President Biden’s effort to forgive student loans. Notably, the Court pointed out, no previous administration had located in IEEPA the power to impose sweeping tariffs. A key reason: “Tariffs are a core Congressional power” that the legislative branch is unlikely to delegate without explicitly declaring its intent to do so.16

Finally, citing a number of Supreme Court decisions, the appeals court rejected the government’s argument that it is inappropriate to construe congressional delegations of power to the executive in the arena of foreign affairs and national security. Whatever the issue, the executive is not free from congressional checks and balances just because foreign affairs are at issue. The power to tax is just as central to Congress as is the president’s lead role in foreign policy and defense.17

The appeals court might have used these arguments to conclude that its reading of IEEPA excluded the imposition of any and all tariffs, citing IEEPA as the legal basis. In a concurring opinion, four members of the majority were prepared to take this step.18 The majority opinion did not. Instead, it interpreted IEEPA in light of the Yoshida decision, which ratified the Nixon administration’s imposition of a temporary 10% duty on imports but stated explicitly that an unlimited tariff authority would not be permitted under the terms of the existing statute, the language of which was incorporated into IEEPA.19 Because Trump’s tariffs are “unbounded in scope, amount, and duration,” they exceed the authority granted to the chief executive under IEEPA.

The dissent mostly accepted the majority’s framing of the controversy as a matter of statutory interpretation but argued that the “natural reading of ‘regulate’ in the phrase ‘regulate . . . importation’ is one that embraces tariffs.”20 More broadly, the dissenters insisted, “We know of no persuasive basis for thinking that Congress wanted to deny the President use of the tariffing tool, a common regulatory tool, to address the threats covered by IEEPA.”21 And contrary to the majority, the dissenters argued that statutes covering the president’s authority in foreign affairs should be broadly rather than strictly construed.22 The dissenters also rejected the majority’s strategy of reading the limits imposed by Yoshida into the interpretation of IEEPA. “We see no sound basis,” they stated, for insisting that “limits in non-emergency tariff authorizations be read into emergency authorizations.”23 And finally, they rejected the application of the major questions doctrine to IEEPA. In a direct appeal to a potentially pivotal justice, they cite Brett Kavanaugh as distinguishing between domestic issues and foreign policy on the ground that Congress usually intends to give the president substantial authority to protect the country and the American people.24

Notably, neither the appeals court’s majority nor the dissenters paid any attention to the argument, advanced by the president and his supporters, that ruling against the president’s global tariff regime would be unacceptably disruptive. The America First Policy Institute warns that a ruling against the president would “eviscerate” his foreign policy and “deprive America of hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue.” President Trump himself has written on Truth Social that “If our Country was not able to protect itself by using TARIFFS AGAINST TARIFFS, WE WOULD BE ‘DEAD,’ WITH NO CHANCE OF SURVIVAL OR SUCCESS.”25 To state the obvious, these are policy and political claims that do not address the core legal issue of whether the president has the authority to impose these tariffs.