Kevin Allenspach

| Special to the St. Cloud Times

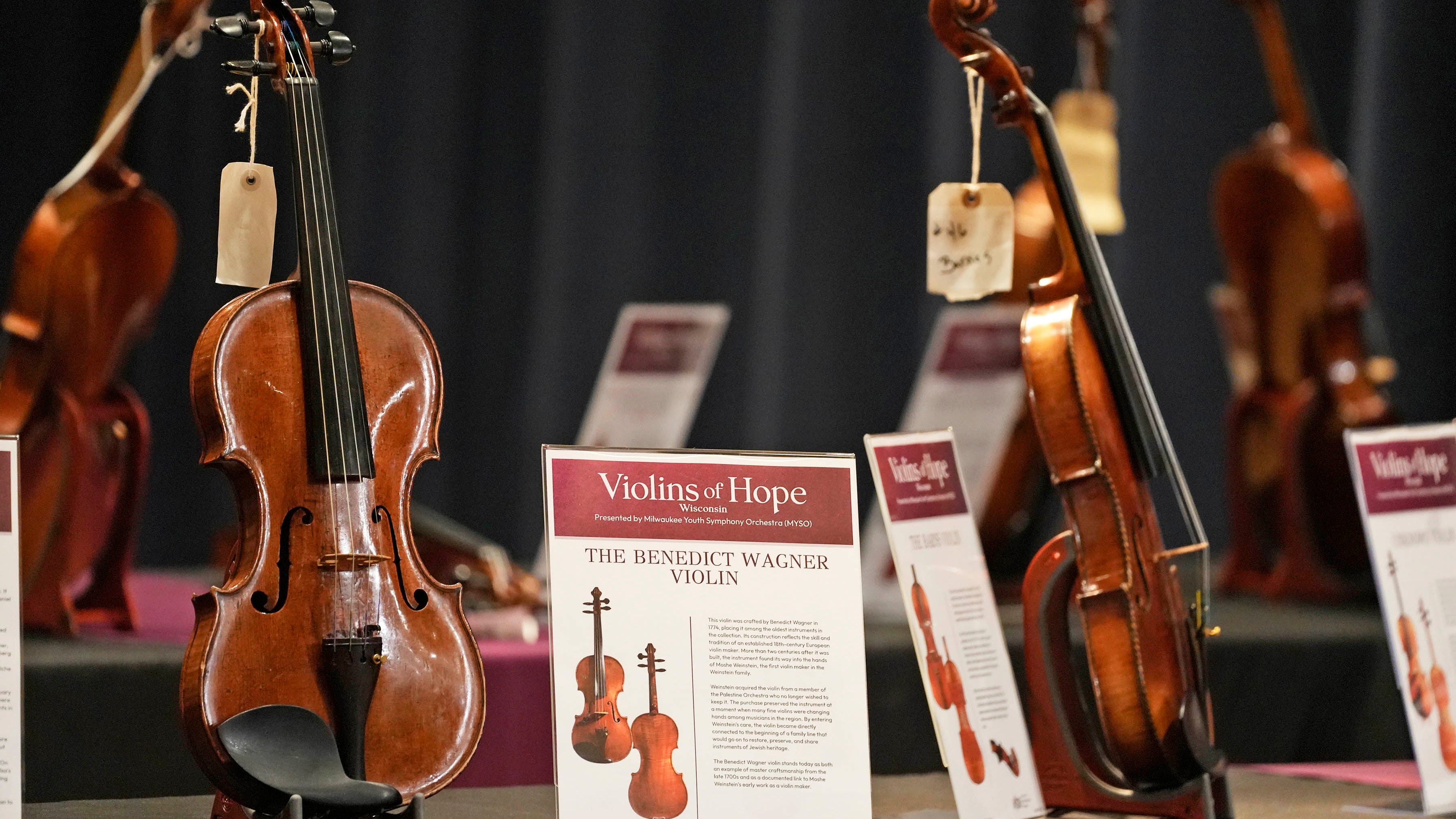

Violins of Hope features instruments rescued from the Holocaust.

Instruments played by Jewish musicians and others targeted by the Nazi during the Holocaust are showcased in the Violins of Hope-Wisconsin.

Maruta Lietiņš Ray, a St. Cloud resident, experienced World War II as a child in Latvia, fleeing both Soviet and Nazi forces.After living in internment and displaced persons camps, she immigrated to the United States at age 10 without knowing English.Ray went on to earn a doctorate and became a university professor, assistant dean, and author.

Before moving to St. Cloud, Maruta Lietiņš Ray experienced loss, captivity, learning new languages and immigrating to a new country.

Born Maruta Lietiņš in 1940 in Latvia, a region soon to be rolled over during World War II by troops from Josef Stalin’s Soviet Russia, Adolf Hitler’s Germany and back again, this young girl experienced occupation and imprisonment.

By 1944, her parents fled west from the communists – only to live in a Nazi internment camp. After peace came the following spring, the young girl, her parents and grandmother lived another five years in a United Nations displaced persons camp before they were able to immigrate to the United States.

Ray, who didn’t speak a word of English at age 10 when she stepped off a former troop transport ship, is now an 85-year-old St. Cloud resident with more than a few stories to tell – something she has been invited to do at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Sept. 16 during a St. Cloud Area Genealogists presentation at the Stearns History Museum. She wanted to preserve her story with historical accuracy for her grandchildren, and those efforts led to her publishing a memoir, Refugee Girl, in 2021.

“I’m not a genealogist – in fact my father didn’t know the names of his grandparents,” said Ray, whose family originally settled in Brooklyn. “So I’m limited in what I’ve been able to learn about my ancestors.”

Records from that era might not have survived or, even if they had, Ray said, they would be in Russian.

“I’ve always regretted not asking my grandmother more about what her daily life was like,” Ray said. “Minutiae like that can get lost in history, and people also don’t tend to talk about their bad experiences. Years from now, I want my grandchildren to understand what my life was like. It sounds like some people here are thinking about writing their family histories, so I’m happy to share how I went about what I wrote.”

If you go: The presentation takes place at 7 p.m. Tuesday, Sept. 16 at the Stearns History Museum, 235-33rd Ave. S., St. Cloud. The program is free for St. Cloud Area Genealogists members and $7 for non-members. Non-members can pay at the door or get remote access through the SCAG online store at https://scagmn.org/store, where an individual annual membership costs $25.

Ray’s story would be remarkable just for her experience as an immigrant, but it’s even more compelling considering she graduated from Flushing High School, a public high school in New York City, in 1958, Barnard College in 1962, earned a master’s degree from Middlebury College a year later, and ultimately a doctorate in Germanic languages and literature from the University of Chicago in 1973. That was where she met her husband, Ben Ray, whom she called “A Maine Yankee through and through,” and they later taught at the University of Virginia, where she was a professor and assistant dean of the College of Arts and Sciences until retiring 20 years ago.

They had two daughters, and in 2018 moved to be near their youngest daughter, Lexy St. Hilaire, who lives in St. Cloud with her husband and three of Ray’s five grandchildren.

While some of Ray’s reminiscences are from very early in her life, she feels she has a gift for remembering. She can recall her experiences in October 1944, when her family lived on little food in a camp near Parchim, Germany. Her father, Karlis Lietiņš, had been a music director for the Latvian National Theater, and her mother, Milda Zilava, was a Latvian film star. As the Russians crept closer, another woman from the theater put on what Ray now calls a “sister” act.

“She was in a different camp in southwest Germany, and she went to the camp commandant, crying that her ‘sister’ was in danger of being overtaken by the Russians, and couldn’t he see his way to get her transferred to where it was safe?” Ray said. “Well, of course it wasn’t her sister, but you did what you had to do. We were able to move (to this ‘sister’s’ camp) and, when the fighting stopped, we were seven kilometers west of the Russian lines.”

While the horror and immediate danger of war were over, the family’s situation didn’t improve much. They were moved to a displaced persons camp near Hanover, in the British quadrant of occupied Germany. A British bomber had crashed nearby late in the war, Ray said, and the local residents refused aid to the flyers – who died from their injuries. As a consequence, she said, the British commandeered the neighborhood homes to house the Displaced Persons, one room to a family.

It took another two years before Karlis Lietiņš was able to get a sponsor and the paperwork necessary for his family to be among the 205,000 DPs admitted into the U.S. under a bipartisan resolution of the 80th U.S. Congress.

“Book learning came easy for me, and fortunately I had been advanced in math while I was in school in Germany,” Ray said. “But there was no (English as a second language) help when I got to Public School 159 in Brooklyn. I carried a dictionary with me everywhere. Some of the first words I knew weren’t spelled correctly, but I heard them from a lot of people everywhere.”

Like, “taki deezy,” which she soon learned was written as “take it easy.” In just a few years she was fluent in English to go along with her bilingual capacity for German and Latvian.

Twelve years after leaving Germany, Ray returned on a Fulbright Scholarship at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz. During the course of her career, she published articles and lectured in German and English about German literature, culture and teaching methodology, and in English and Latvian about Latvian culture, bilingualism and history.

Ray’s husband of 58 years also earned a Ph.D. from the University of Chicago. Education is a hallmark of the family. Their daughters each graduated from Wellesley College, and the oldest, Indra Lovko, went to the University of Virginia School of Medicine and is now a pediatrician. Lexy’s son, Ben, made it to the finals of the Scripps National Spelling Bee in 2020 as a seventh-grader from St. John’s Prep, although he was prevented from participating by the COVID-19 pandemic. The irony of his accomplishment pleased his grandmother no end, though, considering it was at about the same age she was learning English.

“When I think of what could have happened to my parents and I when I was young, I feel very blessed and it makes me truly believe in guardian angels,” Ray said. “There’s a quote I like to recall from one of my favorite authors, L.P. Hartley. He said, ‘The past is a foreign country. They do things differently there.’ It can be fascinating to discover what that means.”

Note to readers: If you appreciate the work we do here at The St. Cloud Times, please consider subscribing yourself or giving the gift of a subscription to someone you know.