About 3,700 Burmese refugees live in Michigan, most of them in Battle Creek

President Donald Trump included Myanmar, as Burma is now known, on a list of countries from which travel to the US is prohibited

Burmese refugees in Battle Creek now wonder what’ll happen to them and what’ll come of their friends and relatives still overseas

Twenty of Par Mawi’s friends have died in war-torn Myanmar in the last four years.

Mawi, a refugee from Burma — as those who oppose the controlling military junta there still call it — made it to Battle Creek, a designated Burmese refugee resettlement site, about 10 years ago. Her daughter never made it.

Now, Mawi and many of the rest of the 3,000 Burmese refugees living in the Battle Creek area worry about their friends and family still overseas after President Donald Trump included Myanmar on a list of about a dozen countries from which travel to the United States is prohibited.

The travel ban has stopped all refugee resettlement in Battle Creek, even as US Rep. Bill Huizenga, R-Holland, called what’s happening there “genocide.” Burmese students studying in America have been trapped overseas when they traveled back to Myanmar to visit family. A spiritual adviser to a Lansing monastery was prohibited from visiting fellow Buddhists in Michigan.

And refugees already living in Battle Creek wonder what’ll happen to them.

RELATED:

“Even though refugees are here legally and have long-term status, they’re wondering if they’ll be impacted at some point,” said Chris Cavanaugh, director of New American Resettlement West Michigan for Samaritas, which helps refugees find homes and survive the first three months when they need everything from social security cards to a credit score. “I’m sensing that hesitation and fear from some of the families, even though theoretically they shouldn’t have it.”

The road is closing

Members of the Asokarama Monastery near Lansing can’t make sense of why the federal government denied a Burmese monk’s visa. He’d visited the monastery multiple times before without incident.

“The picking of the countries on the list seems hard to understand,” said Dr. Than Oo, a Battle Creek kidney specialist who worships at the Asokarama Monastery and who emigrated from Burma, as it was called then, 30 years ago.

Trump’s executive order establishing the travel ban states that refugees are “detrimental to the interests of the United States.”

Subscribe to the Bridge Michigan: Western Edition newsletter

Want more news like this delivered straight to your inbox? Subscribe to the Bridge Michigan: Western Edition newsletter by clicking here.

While 160 refugees have been grandfathered in, none of them are from Myanmar.

“We don’t have any cases scheduled to come that include individuals from Burma,” Cavanaugh said.

According to the administration, the travel ban mostly includes countries that fail at security vetting and from which immigrants tend to overstay their visas.

According to the Department of Homeland Security, Burma had 35 overstays and 789 suspected overstays for nonimmigrant students and exchange visitors in 2023. The department counts suspected overstays when calculating the percentage who overstay their visa.

The percentages depend on the number of people coming to America. So Burma has a 42% overstay rate, while larger countries, such as Brazil, with more than twice the number of overstays, has a 4.6% rate.

Inconsistencies in the logic of the travel bans have been pointed out by groups such as the American Immigration Council.

“Basically, on Day 1 of the new administration, there was a stop work order,” Cavanaugh said. “It seems like there’s not a current appetite in the administration to bring in people at all, legal or otherwise.”

Oo, the Battle Creek kidney specialist, knows of a young Burmese man who is a student in the US. He went back to Myanmar to visit but found he can’t leave.

“He wasn’t issued a visa and now he’s stuck back in Burma — he can’t complete his studies after a three-month summer break,” Oo said.

‘I feel like I have to suffer’

Life in Burma has never been easy, but it has become even more precarious in recent years. There was a military coup in 2021, which has led to civil war. Young men are being forced to join the army while warlords stake out land and citizens try to fight back in the jungle.

That’s not to mention a recent earthquake.

“It’s challenging and frustrating to watch as conditions in some of these places don’t continue to improve after so long,” said Cavanaugh, of New American Resettlement West Michigan.

Huizenga has formed a bipartisan Congressional Burma Caucus to better understand the concerns of his Burmese constituents in Battle Creek.

He’s reintroducing the BRAVE Burma Act, which “would cut off the military junta from the revenue sources it uses to perpetrate heinous acts of violence against the Burmese civilian population,” the congressman said in a news release.

Thousands have fled the country, with 322,173 Burmese living in the US by 2023, according to the Burmese American Community Institute. As of last year, about 3,700 lived in Michigan, according to the Burma Center in Battle Creek. Samaritas has served 1,641 individuals since the organization started receiving Burmese refugees in 2004. Most of those living in Michigan live in Battle Creek.

Mawi is one of them.

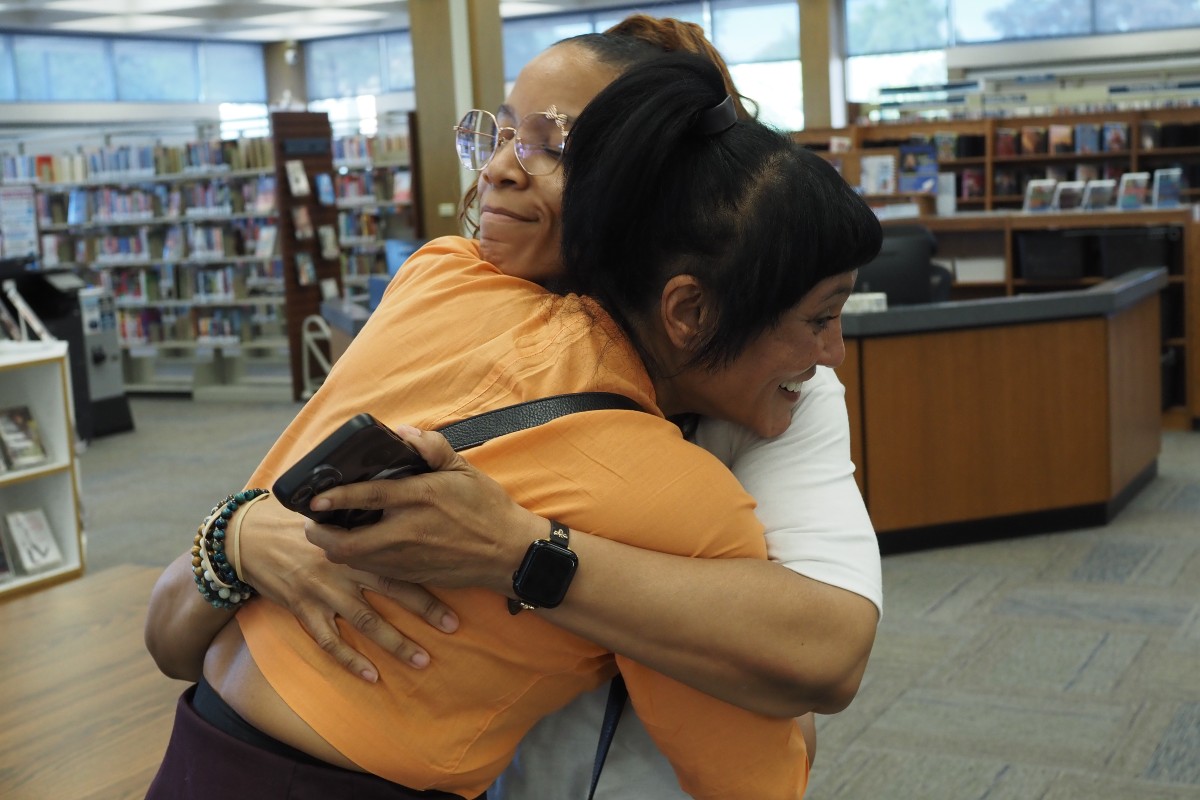

Par Mawi is part of a large Burmese community in Battle Creek. (Annie Kelley for Bridge Michigan)

Par Mawi is part of a large Burmese community in Battle Creek. (Annie Kelley for Bridge Michigan)

She has a son who likes to cook for her. She loves the local library. She finds fulfillment in translation work. She’s a smiling people-person.

But she’s also living with survivor’s guilt.

Mawi was born in Burma during a time of persecution for Christians, something that has gone on since the 1920s. She eventually found her way to a refugee camp in Malaysia, waiting three years for the American refugee process to grind its wheels.

She was granted the papers, but it would be too late for her daughter.

Mawi’s 18-month-old daughter died when the boat on which they were escaping Myanmar was hit by an illegal fishing boat.

“If I’m healing, I feel guilty for my daughter. I feel like I have to suffer,” she said.

“I never feel enough,” Mawi added, “to hearing one of my best friends killed with a bullet through his hat, and stuff like that. I don’t know what else I can do. Speaking out, I never feel enough these four years. And not just me, everyone is losing their family member.”

And Mawi says there are a lot of stories similar to hers. We should be listening to each other’s stories, she thinks.

Those who made it

The travel ban makes Tha Tin Par feel like her loyalty is being questioned, though she moved to America when she was 9 years old.

“It feels like to me that the United States is this parent who has adopted children from broken homes,” she said.

There is still love and hope for the dysfunctional birth parents — the home country — and there are some siblings — new neighbors — who don’t want to accept the adopted siblings.

Mawi said that, during the coronavirus pandemic, someone knocked on her car window and told her to go back to her country.

But Par is thankful to her adopted country, and wants to contribute positively to the family system.

Par Mawi was instrumental in bringing Burmese books to Willard Library in Battle Creek. (Annie Kelley for Bridge Michigan)

Par Mawi was instrumental in bringing Burmese books to Willard Library in Battle Creek. (Annie Kelley for Bridge Michigan)

Mawi once worked at the local library and was instrumental in creating a section of books in Burmese. For her, it was a lesson in the difference between equality and equity.

“When they put me in as Burmese specialist, I felt included,” she said. “So before, I feel like they invite me to the party — I go to the party, I don’t know what to do, I don’t know anyone, and so I’m just standing up and doing nothing. But when they ask me to dance with them, that’s a different story.”

“We’re surrounded by accepting people (in Battle Creek,)” Par said.

Still, there are feelings of helplessness and guilt when faced with the realities of Burma and those left behind.

“The reason we come here is a lot of hard things,” Mawi said, “more than surviving here. So healing takes a lot of time.”

Related

Republish This Story