Romania’s economic convergence remains, beyond the scope of other economic, social, and geopolitical developments, one of the most important transformation processes experienced in recent decades. Rising incomes, expanding infrastructure, and strengthening economic institutions have contributed to improving the quality of life and creating wider opportunities. However, for this path to be sustainable and irreversible, it is essential to understand not only the opportunities but also the vulnerabilities inherent in emerging economies.

The economic cycles of emerging economies have significantly different characteristics from those of mature economies (Aguiar and Gopinath, 2004). The presence of large and persistent external deficits in their case reflects a strong dependence on external financing, which makes them much more vulnerable to possible international shocks and sudden capital withdrawals. In such situations, the risk of a financial crisis is amplified, as countries have to refinance their debts under conditions of increased uncertainty. At the same time, the adjustments necessary to correct external imbalances can be painful for both the economy and society. In addition, as Aguiar and Gopinath note, a favourable period of the global economic cycle, together with “catching-up” processes, do not guarantee sustainable development in the long term. Moreover, in the case of high economic growth rates, it is crucial that they are not accompanied by significant external imbalances, as the combination of rapid growth and large current account deficits can subsequently generate painful economic and social adjustments.

When we discuss the development of economies, we must distinguish different circumstances in which this development process takes place. On the one hand, we have emerging economies that develop within an economic union, as is the case with some countries in Central and Eastern Europe, which have joined the EU bloc. These economies are considered to be small/medium, open, and financially vulnerable. On the other hand, there is the example of the “Asian tigers” – South Korea, Thailand, or Indonesia –, small/medium, open, and financially vulnerable economies, which in the 1980s and 1990s recorded accelerated economic growth, supported by massive investments and dynamic exports, without being part of an economic union. For example, the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) are generally considered emerging economies, but with differences in size, dynamics, and context. However, China, the world’s second largest economy, has a higher GDP than many advanced economies, such as those in the G7 group. Last but not least, countries that we consider to be advanced today were once emerging or developing. Examples in this regard could be Japan or Germany, which, after World War II, experienced major development processes, accompanied by significant economic growth rates.

The study of the convergence process towards an advanced economy can also be achieved by using various quantitative methods, starting from the reference framework provided by the Solow model (1956), to more sophisticated neoclassical models, such as that of Ramsey (1928) or those later developed, based on the Ramsey model, by Koopmans (1963) and Cass (1965).

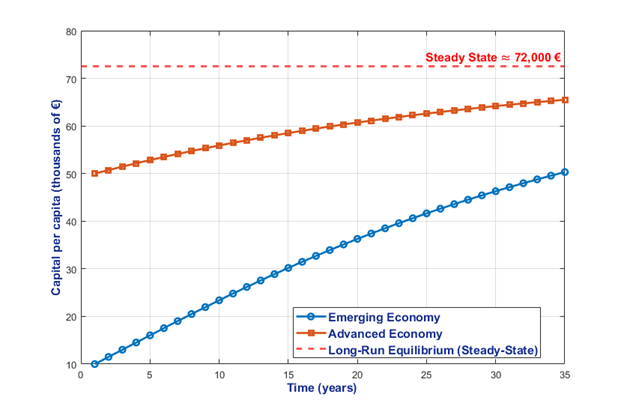

Figure 1: Convergence of economies in the Solow model

Figure 1: Convergence of economies in the Solow model

In order to best represent the convergence process, we have resorted to the parameterization of the Solow model for the case of an advanced economy and an emerging economy in a convergence process. In this quantitative counterfactual exercise, we have considered a relatively standard calibration, where the capital depreciation rate is 5% per year, the saving rate is 20%, while the share of capital in the total income of the economy is 30%. In the exercise, the two types of economies differ in the initial level of capital per capita. Thus, for the emerging economy, we considered a level of capital per capita of 5 thousand euros, while for the advanced economy, the level of capital per capita was calibrated at 10 thousand euros. Since the capital depreciation rate, the saving rate, and the share of capital in the total income of the economy are the same for both types of economies, a long-term equilibrium level of capital per capita of 72 thousand euros results. For the present analysis, we considered a time horizon of 35 years.

From the graph above, it can be seen that capital in the emerging economy registers much higher growth rates. However, once the emerging economy reaches a level of development close to that registered in the advanced economy, the capital growth rate decreases. At the same time, the simulation results show that the 35-year time horizon was not enough for the two economies to reach their long-term potential (within the present model and parameterization), and the emerging economy did not manage to reach a level close to that of the developed economy. Beyond the numbers, equations and parameters, one of the important ideas that can be extracted from here is that emerging economies need sustained efforts over a considerable period of time to approach the level of developed economies.

Using the Solow model, two concepts of convergence can be deduced: absolute convergence and conditional convergence. The concept of absolute convergence is associated with the situation of economies with similar characteristics that tend to approach the same long-term equilibrium level. In this context, poorer countries grow faster than richer ones until growth rates and living standards become comparable. On the other hand, according to the concept of conditional convergence, countries further from their long-term equilibrium level tend to grow faster. According to this theory, after taking into account the differences between the stationary states of the economies, it results that less developed nations grow faster than richer ones.

This simplified theoretical framework provides a clear picture of the evolution of economies, especially within an economic union, and partly explains the economic dynamics of the countries that joined the European Union after 2000. The European economy as a whole has been on an upward trend since the 2008-2009 financial crisis, and emerging economies such as those in Central and Eastern Europe have recorded economic growth and development rates significantly higher than those in advanced economies.

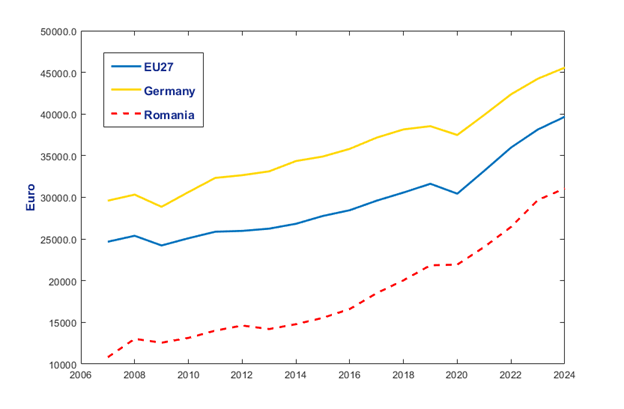

To illustrate the evolution of convergence within the EU, we have presented below the evolution of GDP per capita at purchasing power parity, both as an average at the Union level, as well as for Germany (as a proxy for the euro area) and for Romania.

Figure 2: GDP per capita at purchasing power parity. Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

Figure 2: GDP per capita at purchasing power parity. Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

Looking back, as has often been pointed out and as I have mentioned on other occasions, since the moment of integration into the European Union until now, the data highlight remarkable progress for Romania in terms of real convergence. Gross domestic product per capita, expressed in purchasing power parity, increased from around 10,800 euros in 2007 to around 31,000 euros in 2024 – a tripling in 17 years. We chose this measure expressed in PPS because it more accurately reflects the real purchasing power of the population, allowing for meaningful comparisons with other EU Member States, regardless of differences in prices and living costs. As shown in Figure 2, the trajectory of GDP per capita in Germany aligns closely with the broader trend across the European Union.

To obtain a clearer picture of the decoupling of common factors felt at European level and those specific to Romania, we have extracted and presented in the graph below the cyclical component from the GDP per capita series. To this end, we used the one-sided version of the Hodrick-Prescott filter, where the lambda smoothing parameter was calibrated to the value of 100, in line with the annual frequency of the data.

Figure 3: Cyclical developments for GDP per capita at purchasing power parity. Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

Figure 3: Cyclical developments for GDP per capita at purchasing power parity. Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

In Figure 3, we can see a higher volatility in the case of our country compared to the case of Germany or the European Union. Also, the variations of the cyclical component in the case of Germany show a lower magnitude than in the case of the European Union, which is natural, because the average reported at the EU level reflects both more volatile developments related to the member states with emerging economies, and the more stable ones related to the large and much more developed economies.

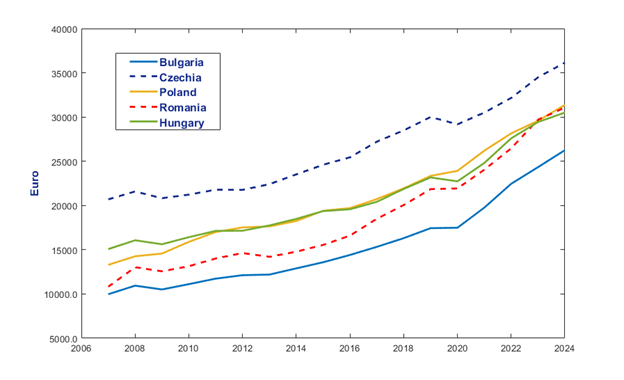

For Central and Eastern Europe, the developments presented in Figure 4 highlight the fact that Romania had one of the fastest and most sustained GDP per capita dynamics in the region. At the time of accession to the European Union, our country ranked above only Bulgaria. At the same time, Hungary’s GDP per capita was higher than that of Romania and Poland. About 18 years later, in 2024, Romania’s GDP per capita was very close to that of Poland and higher than that of Hungary.

Figure 4: GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in Central and Eastern Europe. Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

Figure 4: GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in Central and Eastern Europe. Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

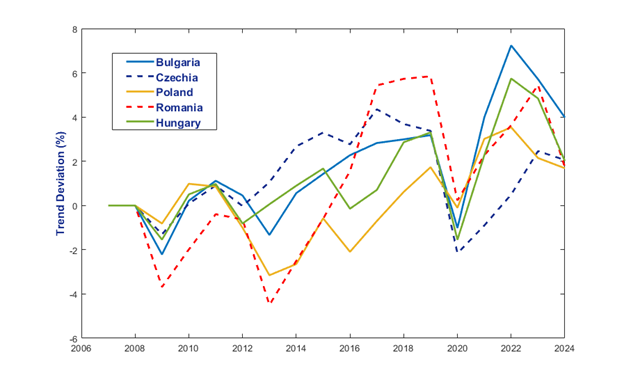

For a more detailed picture of the convergence process, in Figure 5 below, we have reported the cyclical developments of the GDP per capita for the entire region. This time too, we used the one-sided version of the Hodrick-Prescott filter, where the lambda smoothing parameter was calibrated to the value of 100, given the annual frequency of the data. From the developments presented, it is observed that the cyclical series obtained for our country records wider variations, with a clearly more pronounced magnitude in the expansion phase.

Figure 5: Cyclical developments for GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in Central and Eastern Europe. Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

Figure 5: Cyclical developments for GDP per capita at purchasing power parity in Central and Eastern Europe. Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

The general results of the counterfactual exercise built on the Solow model applied to the dynamics of the economies of the European Union member states suggest that, despite a relatively higher level of development of some Eurozone states, such as Greece or Portugal, compared to that of the countries in the last wave of accession (including Romania), reaching the potential level of development is not a certain result. Therefore, the decisions and the way of implementing economic policies are relevant and can lead to the confirmation of the development potential or, on the contrary, in the case of some mistakes/inconsistencies, can result in a development below potential.

On the other hand, when the potential level of development is substantially below that of the advanced economies within the bloc, it is unrealistic to expect a high degree of convergence to be achieved in the short or medium term. Therefore, for the economic development of the countries that joined the European Union after 2000, both the general growth of the entire economic bloc (i.e. the inertial effects specific to the catching-up process) and the specific advantages of each country, correlated with the expansion phase and the initial level of development, mattered.

Regarding the evolution of the Romanian economy in the period after accession, two questions of interest can be formulated: (1) how intense was the integration into the European Union, and (2) how did the other economies of the region behave.

To formulate an answer, we resorted to the approach proposed by Robert Lucas in his 2007 paper Trade and the Diffusion of the Industrial Revolution. Thus, during the period 2007-2024, we determined that the average annual (logarithmic) rate of growth of GDP per capita was approximately 6.21% in Romania, and approximately 2.8% at the European Union level.

It is important to note that emerging economies, such as Romania, register not only increases in production, but also adjustments in the price level towards the European Union average. This alignment of prices, reflected in indicators calculated at purchasing power parity, can lead to a growth rate of GDP per capita expressed in purchasing power parity higher than that of real GDP, thus expressing progress, both in quantitative terms and in terms of relative prices.

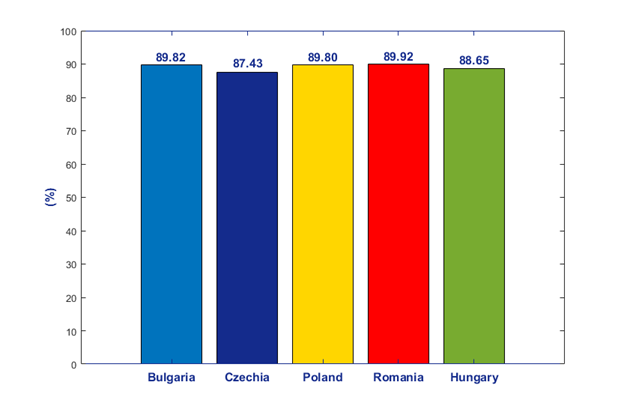

Calibrating the Lucas model results in an integration parameter of approximately 0.8992. This indicates that Romania assimilates, on average, approximately 90% of the benefits of membership of the European Union, referring here to technology, productivity, European funds, or foreign direct investment.

In Figure 6 below, we have reported the integration parameters obtained based on the Lucas model for the other countries in the region as well. The estimates obtained highlight the fact that our country has the highest integration parameter, but the differences between countries are not large.

Figure 6: Assessment of the degree of convergence in Central and Eastern Europe using the Lucas model (2007). Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

Figure 6: Assessment of the degree of convergence in Central and Eastern Europe using the Lucas model (2007). Source: EUROSTAT, own calculations

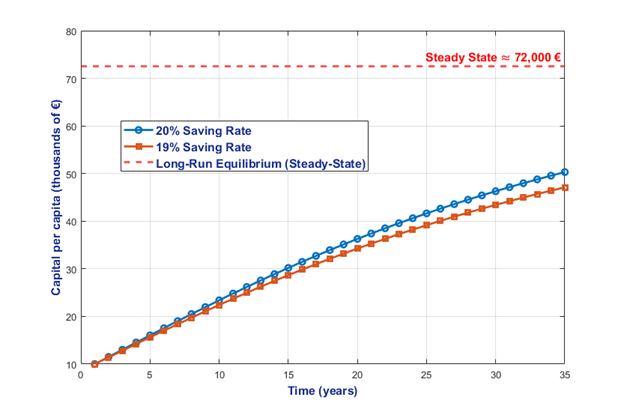

Given the importance of domestic saving for long-term economic growth and capital accumulation, we constructed a second counterfactual exercise, using the analytical framework of the Solow model.

Thus, we considered two emerging economies, where the level of capital per capita is 5000 euros, the rate of capital depreciation is 5% per year, while the share of capital in the total income of the economy is 30%. The two economies differ only marginally, through savings rates of 20% and 19%, respectively. The results presented in Figure 7 indicate that, after a 15-year interval, the difference between the two economies in terms of capital per capita begins to increase. At the end of the 35-year horizon, the economy characterized by a slightly higher saving rate registers a level of capital per capita approximately 6.8% higher than the other.

Figure 7: Convergence of savings in the Solow model, considering different savings rates. Source: own calculations

Figure 7: Convergence of savings in the Solow model, considering different savings rates. Source: own calculations

Based on the above analyses, we can formulate a series of observations relevant to the current economic and macro-financial policy context.

First of all, it is essential to be aware of the fact that the convergence process generates irreversible transformations in the economy. For Romania and most of the countries in the region, the context after the financial crisis was marked by a unique combination of factors, which should not be used as a benchmark in analyses or projections regarding the future, as the likelihood of its recurrence is low. As highlighted by Nakamura, Steinsson, Barro, and Ursua (2010) or Gabaix (2010), financial crises are often followed by high economic growth rates, as part of the recovery process. In addition to this aspect, after the financial crisis, Romania benefited from large inflows of investment and European funds, a global phase of expansion of financial markets, as well as a significant fiscal space that allowed for the stimulation of the economy. Last but not least, the unprecedented period characterized by a very low level of interest rates allowed for the stimulation of consumption and investment.

However, from the analysis of Fernández-Villaverde, Ohanian, and Yao (2023) we deduce that these extremely beneficial circumstances are not sufficient to guarantee convergence in a rapid time horizon, not even in the case of a spectacular development like that of China. Moreover, high rates of economic growth in the past are no guarantee, neither for high rates of growth in the future, nor for a permanent increase in productivity.

On the other hand, when high rates of economic growth are harnessed through domestic capital accumulation, efficient allocations in the economy and sustained advances in productivity, one can anticipate an increase in long-term potential, the maintenance of a robust pace of economic activity, as well as sustainable development, accompanied by a reduced level of macroeconomic and financial volatility.

To ensure high real convergence in the long term, the Romanian economy needs a development model adapted to the new conditions. This should aim, among other things, at consolidating the domestic capital base, developing financial markets, increasing productivity (through investments in education, innovation, technology and infrastructure), making efficient use of European funds for projects with a high multiplier effect and diversifying sources of growth (by stimulating exports and SMEs). Thus, Romania can and must transform the conjunctural advantages it has had so far into a sustainable development model, based on stability and increased competitiveness. The process of capital accumulation can open up multiple opportunities for progress, including by strengthening the interaction between the public and private sectors.

For Romania, more than for other Eastern European countries, the middle-income trap is amplified by twin deficits, which makes it necessary to move towards a growth model based on fiscal and budgetary discipline, innovation, technology transfer, and clear rules that stimulate entrepreneurship.

The real challenge for an emerging country is the courage to change its development model, and to this end, the opportunity offered today by innovation, the digital transformation of products and processes, and the use of artificial intelligence to increase productivity and competitiveness must not be missed. We need as many innovative companies and centres of excellence in research and innovation as possible. We need all the national human capital resources and a widespread understanding in society and the business environment of the importance of this country project.

The current situation allows emerging countries that are prepared, determined, and consistent to go through certain stages of development more quickly. At the same time, however, there is also the risk of remaining only consumers of technology, not creators, which would slow down the convergence process.

In the logic of development, emerging countries must look beyond economic calculation, towards a true metamorphosis, by replacing a limiting vision of imitating known experiences and models with a new paradigm that will shape their future. For sustainable growth, it is necessary to assume the transition to a society that encourages innovation and the development of new technological solutions, precisely in order to avoid being stuck in a slow pace of development. But this metamorphosis does not only involve new technologies, but also the transformation of institutions, processes, and mentalities.

For countries caught in the middle-income trap, capital alone is not sufficient; the development of a culture of creativity, innovation, and trust is equally essential. Without it, the risk of being trapped in a zone of stagnation increases significantly. Therefore, the necessary transition requires confronting still deeply rooted mentalities and interests, for a profound change of vision by realizing the need to change the development model on the one hand, and, on the other, by focusing on innovation as the engine of growth.

The new wave of technological revolution is no longer merely a shift in the means of production, but a redefinition of how societies create value — and for emerging economies, the opportunity is greater than ever.