Sometimes a single sentence carries the soul of an entire nation. A centuries-old tree withered away, its trunk dried and left standing like an unfinished story. In most places, such a tree would quietly disappear into silence. But not here.

Here, the authorities placed a plaque beside it with a simple yet powerful lament: “WE ARE SORRY, WE COULDN’T PROTECT YOU.”

Even more remarkably, the entire history of this tree has been recorded here. And the language of that account is written as if the tree itself is speaking. It says: “We, two brothers, thrived and grew up here with people’s love, compassion and care. We extended our branches everywhere and grew taller. While we were living happily together for 350 years, one day in 2018, someone came and cut off my roots for nothing! I was surprised a lot! What have I done to you? We have never experienced such evil in our entire lives. Then a philanthropist, patriot and nature lover heard about it and came running to me. He checked my wound and bandaged it. They tried to save me with various efforts, but it didn’t work. It was impossible for me to live! I was bone dry. I finally died. That benevolent person, who could not bear this pain, undressed me to be a lesson to the world, wrapped me up to protect me from the sun, rain and cold and turned me into a wooden statue. As a reminder and a lesson to you people!”

As I read these words, tears welled in my eyes. My mind drifted back to the time when I wrote about the felling of more than 50,000 trees in India’s capital, Delhi – a figure I had obtained from the Delhi government through the Right to Information Act (RTI). Then, in 2021, I learned that thousands more trees would be cut down as part of the Central Vista Redevelopment Project to build India’s new Parliament. Back then, I felt powerless. All I could do was pour my grief into a poem – one where the trees themselves were speaking to each other, asking a single haunting question: “Why is it that we are always in the way?”

I was still lost in these emotions when my companion called from behind – “Come on!” It felt as if someone had suddenly shaken me awake from a dream. I walked forward with my two friends, yet my mind remained with that tree – and with the administration that chose to keep it alive by inscribing words upon it even after its death. It reminded me that shame, too, can be a force; that even a sense of loss can leave behind a legacy and a history. And if any country could do such a thing, it is Türkiye.

This country has mastered the art of preserving the history of trees. In the village of Inkaya, in Bursa, stands a 600-year-old Çınar (plane tree) – celebrated around the world for its strength, grandeur and breathtaking beauty.

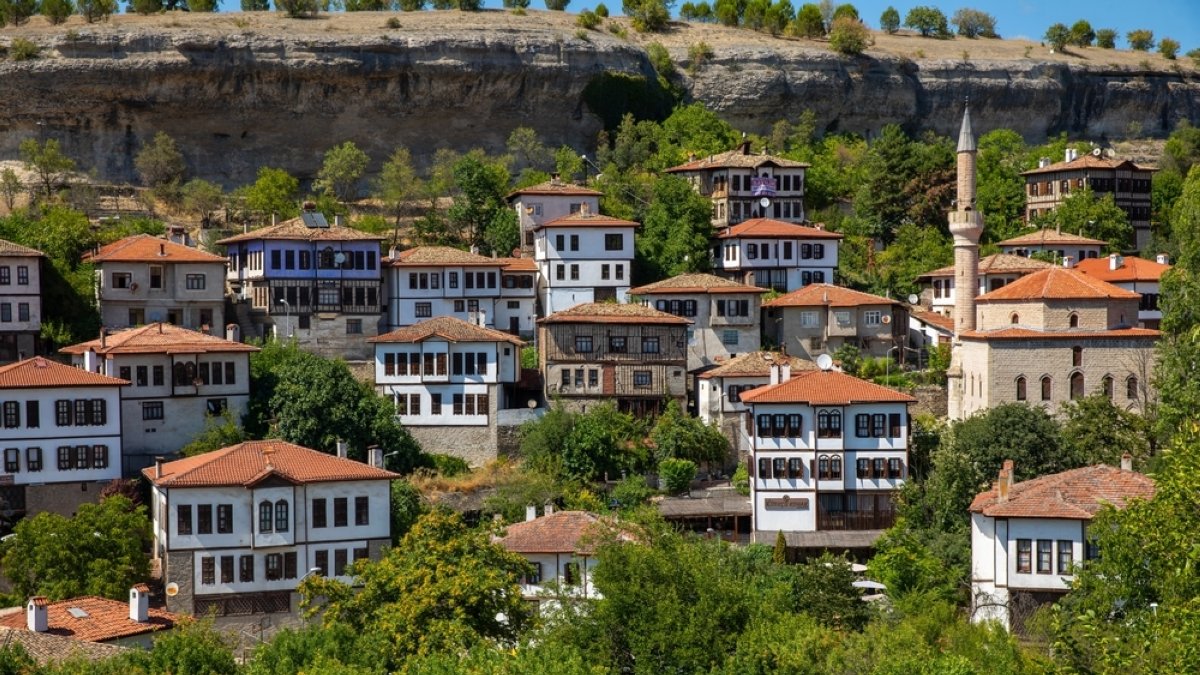

But I am not speaking of Bursa. I am speaking of another village – Safranbolu – which UNESCO added to its World Heritage List nearly 31 years ago, on Dec. 17, 1994. Safranbolu lies in the north of Türkiye’s historic Karabük province.

When I walk through cobblestone streets, centuries seem to pulse beneath my feet, reaching straight to my heart. These streets aren’t just paths – they are tunnels through time.

The arches of mosques, the domes of historic hamams, the Cinci Han caravanserai, the coffee museum, the chocolate museum, the Arasta Bazaar, the skilled craftsmen, the old utensils and swords and even every single house – they all whisper stories of a bygone era. Every corner seems to speak of Turkish culture, inviting you to listen.

What fills the heart with the deepest satisfaction is knowing that Türkiye has preserved Safranbolu with care not only for history but also for the environment. The breath of the old houses has not been stifled by new constructions. Here, preservation extends beyond buildings – it embraces the air, the light, the trees and the sky.

Safranbolu is truly a living book, its pages still damp with the ink of time. As I walked through its streets, I felt as if this was the very moment when a poet, in the quiet of his soul, writes his greatest poem – a poem that lives eternally in the stones, the scents and the memories of people.

Along the way, I passed shops selling traditional utensils, swords and knives. In the heat of the day, I saw a craftsman forging swords, heating iron in a blazing furnace – a scene that took me back to my childhood in India, now so rarely witnessed in my own city.

Moving forward, I came across 400-year-old hidden tunnels, where two musicians were playing a hauntingly beautiful Turkish melody. As their music echoed through the tunnels, I watched the water channels below, feeling suspended between past and present. Meanwhile, the poet in my mind remained awake. Suddenly, a singer behind me asked, “Nerelisin?” (Where are you from?)

When I said India, he began playing the tune of the song “Awara Hoon” and sang along. Not stopping there, he recalled other Indian songs too. I was amazed that he knew the names of all the Indian singers. I spent about 10 minutes talking with Ney player Selim Yorulmaz. There was a unique, indescribable feeling in that conversation – one that words alone cannot capture in “Do Lafzon” (two words).

The time had come for this “Awara” (“wanderer”) to leave Safranbolu. I felt compelled to look at that tree one more time – to let the message of preserving trees sink deeper into my heart. And when I saw it, a new hope was born within me.

You might be surprised to learn that this “dead tree,” now preserved as a statue, has a young sapling growing from its roots. Beside it, another tree stands fully green, its branches stretching in every direction. For context, these two trees were planted after the construction of the Köprülü Mosque in 1661, built by the famous Ottoman minister Köprülü Mehmet Pasha.

I sincerely hope that this “dead” tree will one day come back to life, just as it once spread its branches over the mosque courtyard like a protective umbrella. On hot summer afternoons, its leaves offered cool shade to all who sought it. Just as it hosted photographer Yaqub Ustad for years, just as it shared in the sorrows of the local people and celebrated with them during Eids, those days of life and presence will surely return. And when I return to this village during the saffron season, I hope to witness it myself.

I also hold hope that, just as the trees lost in sudden forest fires across Türkiye will soon sprout again, life and green vitality will return to these trees as well. Finally, I offer my greetings to the Safranbolu Culture and Tourism Foundation.