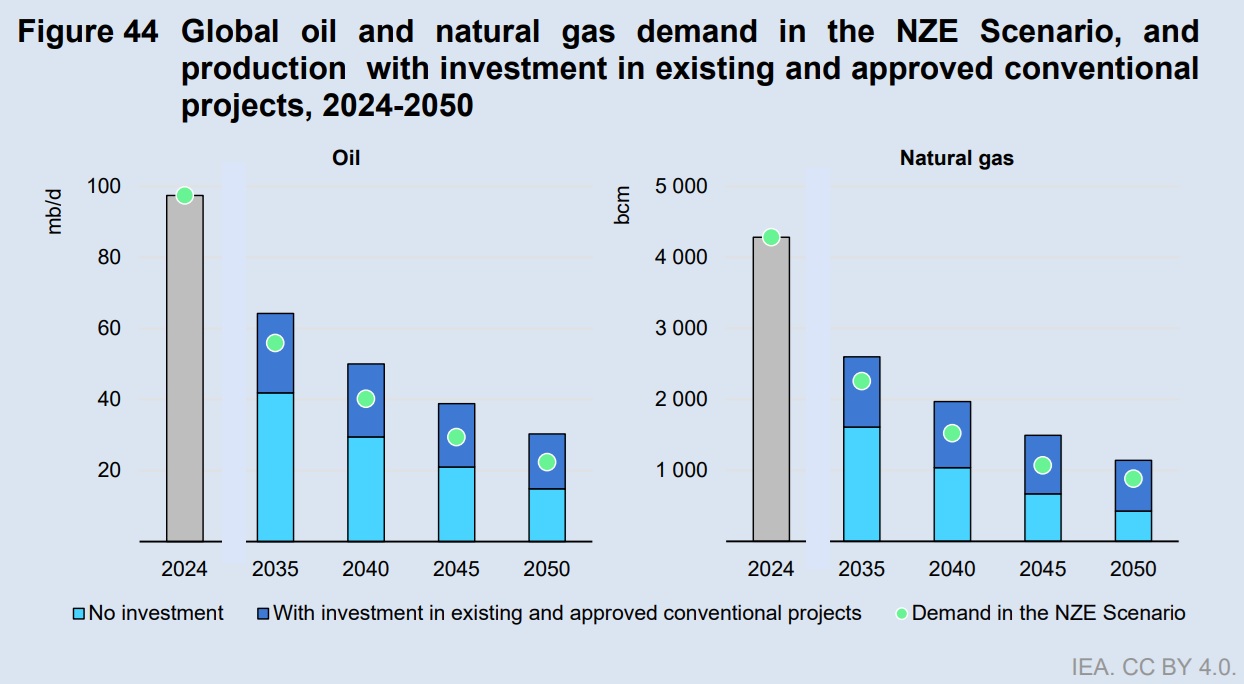

The world is set to pump far more oil and gas than it would use if it is to meet the 1.5C warming limit endorsed by governments in the Paris Agreement, according to new analysis from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Meeting the Paris temperature target would mean shutting down production of eight million barrels a day of oil and 250 billion cubic metres of gas a year by 2050, the IEA said in a report this week – roughly equal to Saudi Arabia’s oil and Iran’s gas output today.

Back in 2021, the agency made headlines by declaring there was “no room” for new fossil fuel production projects in a 1.5C warming scenario.

But this week, it added that – with the 1.5C scenario’s projected rapid drop in oil and gas demand – “several higher cost” oil and gas production projects should be shut down “before they reach the end of their technical lifetimes”.

Green dots show demand for oil (left) and gas (right) in the 1.5C scenario, with the blue columns showing projected supply (Photo: IEA)

While the IEA did not name any specific projects, it has previously identified oil projects in Canada, China and Algeria and gas projects in Australia, Argentina and Malaysia as among the most expensive. The cost of extracting oil and gas varies, mainly depending on geographic and geological factors.

Kelly Trout, research director at Oil Change International, said that the IEA’s findings show “countries must follow through on their internationally agreed commitment to transition away from polluting fossil fuels, and invest in a renewable energy future”.

Buried in a box

Despite those findings, a press release accompanying the report led with warnings about the “implications for markets and energy security” of slowing production in oil and gas fields – an aspect many media articles focused on. The IEA has come under pressure from the Trump administration in the US to promote fossil fuels.

The 1.5C warming scenario, meanwhile, was buried in a three-paragraph box near the end of the 73-page report.

The report found that most of the cheapest and easiest-to-access oil and gas reserves have already been extracted, “leaving primarily smaller, deeper and more technically challenging fields” which are often deep under the sea.

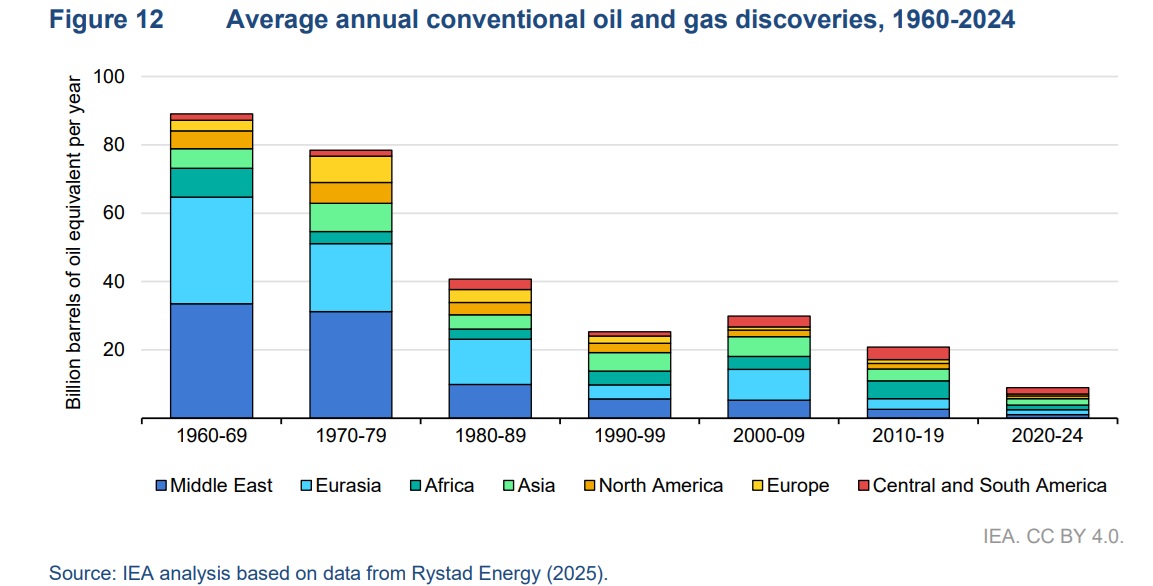

Despite recent large discoveries of oil in Guyana and gas in Mozambique, the amount of conventional oil and gas discovered has been declining since at least the 1960s, the report found. Over the last ten years, oil and gas companies have been spending less and less on exploration.

Average annual conventional oil and gas discoveries by decade, with the last column covering only four years. (Photo: IEA)

Of the $550 billion spent annually, about $500bn simply replaces declining fields. Only $50bn goes to new supply, the IEA estimated.

Guy Prince, head of energy supply research at Carbon Tracker, told Climate Home that the big publicly traded oil and gas companies “are being cautious, quietly retreating from energy growth and instead returning cash to shareholders”.

In 2024, Rystad analysis shows that six of these big companies paid out a record $119 billion to shareholders, leaving them with less cash to invest in producing oil and gas.

Prince said the shift to electric vehicles poses the biggest threat to future oil demand.

US pressures the IEA

The IEA projects in both its “announced pledges” and its “stated policies” scenarios that demand for both oil and gas will peak before 2030. These projections have angered US Republicans who worry they will disincentivise investment in oil and gas extraction.

US Energy Secretary Chris Wright called these projections “nonsensical” and said in July that the US will leave the IEA if it cannot reform it.

US Energy Secretary Chris Wright at the CPAC conference in 2025 (Photo: Gage Skidmore)

The IEA has said it will re-introduce a more pessimistic projection, called the “current policy” scenario, to its flagship World Energy Outlook report, to be published alongside other scenarios. According to Bloomberg, a draft of the report shows that this scenario projects oil and gas demand rising into the 2050s.

Greg Muttitt, a researcher at the International Institute for Sustainable Development, wrote in a post on Linkedin that the IEA’s stated policies and announced pledges scenarios’ projections of a pre-2030 oil peak are backed by estimates from oil companies like BP and Equinor, as well as consultancies like McKinsey.

“The US Administration wants people to believe that fossil fuels will have a bright future, hoping that this can become a self-fulfilling prophecy,” he added. “But overly-optimistic fossil narratives lead to economic risks, both for investors and for countries whose economies depend on oil & gas revenues, such as Nigeria and Iraq.”