In an underground room of the Syrian National Opera, the air vibrates with the sharp, icy strokes of Antonio Vivaldi’s Winter – Allegro non molto.

The next piece, with its shifting melodies and interplay between the two pianists, demands focus and skill from both Tareq Daud and his partner Marina Bogaichuk; Danse Macabre requires them to convey a rich, complex history using sound alone.

The artists have been meticulously refining their repertoire for months, eager to finally share it with the audience at the Syrian National Opera.

But each time the concert seemed within reach, it was postponed.

Sometimes it was bureaucratic: the Ministry of Culture hadn’t given the final green light. More recently, in June, just three days before the planned performance, an Israeli rocket struck the neighbouring Defence Ministry, shaking the Opera itself.

That day, Daud arrived at the Opera just minutes before.

“It was the most terrifying experience in my life. The blast, the sound,” he recalls talking to The New Arab in Damascus.

Shattered windows and broken doors still scar the building, unsafe for guests. More than a month and a half later, yellow caution tape is the only warning of the damage, and the artistic duo remain in limbo, uncertain when — or if — they will ever be able to play.

Pianist Marina Bogaichuk [Collin Mayfield]

Pianist Tareq Daud [Collin Mayfield]

Overcoming challenges

These questions continue to haunt many Syrian musicians today, including Missak Baghboudarian, conductor and director of the Opera.

Speaking with The New Arab in his office, he pauses to take a deep breath, collecting his thoughts before sharing his perspective on the state of classical music in Syria today.

“It’s about a political vision of the role of the culture in the life of the society and the life of the country,” he explains.

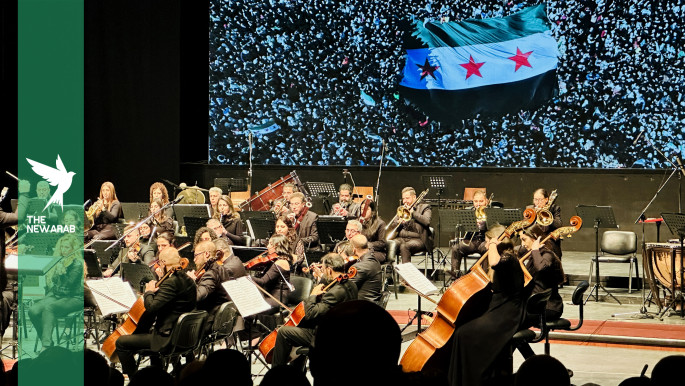

The Syria- and Italy-educated principal conductor of the Syrian National Symphony Orchestra took the helm of the Opera during a turbulent period of transition: December 2024, when HTS-led rebels seized power and overthrew the decades-long Assad family regime.

In the first days after coming to power, some HTS members visited the Opera House, with Baghboudarian guiding them through the building.

“For them, it was like discovering a new concept,” he recalls.

“I showed them around the Opera House and explained that there are people here who make a living from music — and that it’s respectful music performed at a high level,” he told The New Arab.

“The audience comes to listen, not for entertainment like in a nightclub. I’m sure that once they attend a concert, they’ll understand exactly what I mean. But so far, we’ve never had the chance to have them at a performance.”

Maestro Missak Baghboudarian [Collin Mayfield]

But the challenges facing Syria’s musicians stretch much further back.

“Even in the best of times, in the 1990s, when things were stable, the audience for European classical music was relatively small,” says Jonathan Shannon, anthropologist and a musician teaching at Hunter College in New York City.

“There was already a disjunction between what the state was promoting and what the actual people wanted to hear.”

The Higher Institute of Music, he added, focused “almost entirely on European classical music, to almost what I would call benign neglect of Arab music.”

That tension left its mark.

“Soheil Luadi, who was a very excellent musician and conductor, himself had very little regard for Arab music. And so, when he directed the institute, the focus was almost entirely on European music,” explains Shannon.

Most teachers came from the former Soviet Union — “second or third tier, but outstanding,” he recalls. Many Syrian musicians also studied in Moscow, creating what one called “strong connections with Moscow.”

Creativity under fire

Syrian artists and musicians face growing fear for their future as violent attacks and moral policing threaten creative expression.

Despite efforts to reclaim “free spaces of creation” after Assad’s fall, incidents like the armed raid on a Damascus nightclub targeting women, a club shooting, and a concert hall attack in Idlib have stoked anxiety.

While some cultural activities continue, artists worry that fragile freedoms could be swiftly undone by violence or strict ideological control.

Certain difficulties are anything but new or unfamiliar to musicians and other artists in Syria. During the Assad era, political restrictions heavily affected artistic expression, and artists were never entirely free. However, as Baghboudarian notes, the situation tended to be somewhat more relaxed for classical musicians like them.

“In music, you don’t have words. You are an interpreter, performing what the composer asks or intends you to convey,” he explains.

Musicians in Syria often faced severe repercussions if they engaged in political activism or opposed the regime. Loyalty to Assad frequently outweighed talent, and those who showed dissent — or were linked to dissenters — were sidelined, expelled from orchestras, or otherwise punished.

For example, after the 2011 revolution, music professor Muhammed Azzawi was expelled from the Syrian National Symphony Orchestra following his ex-wife Fadwa Souleimane’s activism, highlighting the personal and professional risks artists faced.

For Baghboudarian himself, during the difficult and divisive years of the civil war, music became a way to hold a fractured and traumatised society together, offering people a soothing refuge from the daily horrors.

“This is what we discovered during the war. In 2011, when it started, for two or three months, all of us musicians were asking ourselves: ‘Should we continue our concerts or not? Should we play? What should our position be in all that is happening in Syria?’

“Then we started to get messages from the audience, from the people who used to come to our concerts, asking: ‘Why are you not performing? Where are the concerts?’ That’s when we began to understand that music isn’t a luxury for society — it’s a necessity. We realised we have a duty: to perform, to bring people together, to give them hope. At that moment, I felt that we were like hospitals — not for physical illness, but for moral illness. People needed us,” he says.

Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff and Dvořák were among the favourite composers of the Syrian public. “Our audience is very emotional,” Baghboudarian explains with a smile.

Holding on to hope

In 2014, the Opera itself became the target of a mortar attack where two students from the adjacent Higher Institute of Dramatic Arts were killed, and several others were seriously wounded.

But Baghbourian confesses that now, in these seemingly peaceful times, he struggles more than ever. Since December, the Opera has managed to stage only two concerts, both funded by private organisations.

The Damascus Opera House is the national opera house of Syria [Getty]

Just two days before our meeting, the Culture Ministry issued a new order for students graduating from the Art Faculty. For the first time, their yearly projects cannot include any nude scenes, putting students who had planned to incorporate them at risk of failing and potentially being unable to graduate with a diploma.

“This is not a good signal for us as artists,” sighs Baghbourian.

Looking back, Shannon reflects that the whole Opera project was always part of a state “modernising project” – a desire to show the country becoming Western.

“As we find in many nations, Syria, founded as an independent nation in 1946, had this idea that to become modern, you have to become kind of more Western. You have to have a Western-sounding national anthem. If you hear the Syrian national anthem, it’s as boring as any other national anthem. It doesn’t have microtonality. It’s played with trumpets.”

Today, however, Baghboudarian worries less about Westernisation and more about survival – both of institutions and of talent.

“Another major challenge is encouraging young musicians to remain in the country and pursue their craft despite the hostile environment,” he warns.

Syria’s economic crisis is pushing them abroad, and he fears another wave of emigration would be devastating.

During the civil war, many were invited by wealthy Gulf countries to live and perform there. The conductor now fears that the current situation could trigger yet another wave of young talents leaving, which would be a profound loss for Syria and its people.

Yet he clings to a core belief: “Music carries an important message: it cares for people. It has no words, no slogans – only feelings, vibrations that bring people together.

Especially now, when hatred and divisions are rising, music can unite people, allowing them to share human emotions for one or two hours in the theatre. That night, they feel that this is important.”

Shannon, while acknowledging that the future of music in Syria is “uncertain,” remains cautiously optimistic.

“The Syrians I’ve known for the past 30 years want peace and stability like anyone else. They are proud of their culture. They don’t want to repeat it over and over — they want to preserve it while also building on it.”

As of September 4, pianists Tareq Daud and Marina Bogaichuk are still awaiting final approval from the Ministry of Culture for their concert.

After months of delays and uncertainty, the two musicians remain hopeful that this time, the stage will finally be theirs.

Jagoda Grondecka is an award-winning independent journalist focusing on Afghanistan and the Middle East. She is currently reporting from Lebanon

Follow her on X: @jagodagrondecka and Instagram: @grondecka