The huge amount of fake news and disinformation online can make sorting fact from fiction a challenge for everyone.

In Estonia and neighboring Latvia, those who get their news from Russian-language media increasingly find themselves exposed to misleading narratives and all the dangers associated with them.

Now, an EU-funded project called “Fake Detective” is helping Russian-speaking youngsters in the two Baltic countries to better identify fake news, understand propaganda and think critically about information they encounter online.

But “Fake Detective” is not just about lecturing Russian-speaking teenagers on the evils of the internet. Instead, it encourages participants to play an active role in debunking myths they’re exposed to.

Young Russian-speakers from Estonia take part in a “Fake Detective” workshop in Narva. Source: Press materials

Young Russian-speakers from Estonia take part in a “Fake Detective” workshop in Narva. Source: Press materials

“By using creative formats — such as games, art and workshops — we can strengthen their ability to recognize manipulative content, increase their resilience to harmful narratives and help them feel more confident in navigating both local and global information spaces,” Dmitri Fedotkin, one of the leaders of the “Fake Detective” project in Narva, Estonia told ERR News.

Personal stories

From sharing personal stories about falling for online hoaxes to holding discussions on why some forms of propaganda are so convincing, “Fake Detective” aims to provide young people with the tools they need to build resilience against disinformation.

Participants then use the insights gained to create short animated films showing how easily fake news can spread, as well as ways to avoid being caught out by it.

One video made during the project by Svyatoslav Lavrov, a young Russian-speaker from Estonia, draws attention to the prevalence of misleading images on the internet. In Lavrov’s video, which is set in Narva, a girl receives a photo showing children riding an elephant in a playground. She invites her friend to join her but when they arrive, no one is there. The boy then realizes the photo was fake.

The idea came from Lavrov himself, who after encountering numerous examples of fake images online, wanted to highlight how easy it is to be tricked into believing everything you see.

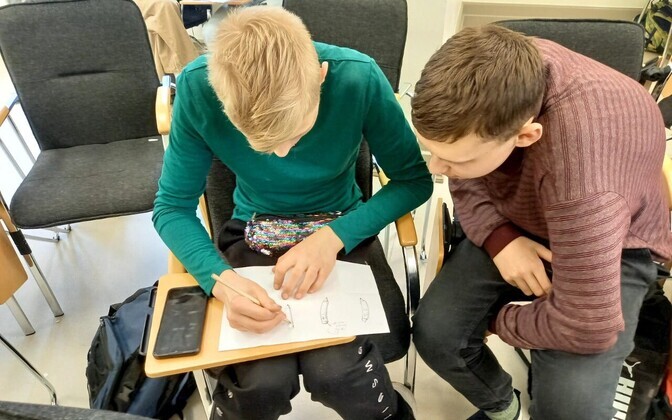

Participants in the “Fake Detective” program in Narva, Estonia. Source: Press materials

Participants in the “Fake Detective” program in Narva, Estonia. Source: Press materials

“Young people need to be engaged in order to really take part in the process and creative methods work best for this,” Fedotkin explains. “Animation, discussions and game elements make the topic approachable and relatable, while also creating a safe space where participants can share their own experiences.”

In the beginning, however, one of the biggest challenges for the project was making fake news an appealing topic for young people to explore. “Many see disinformation as something distant or ‘for adults,'” Fedotkin says, “so we had to find creative ways to capture their attention.”

Fedotkin points out that by doing so, they are able to show “that checking information can be interactive and even enjoyable — not just a ‘boring school task.’ This approach also encourages teamwork, creativity and critical thinking — all of which are essential skills for recognizing manipulation and resisting harmful narratives,” he says.

Media habits

In the Estonian border town Narva, where workshops in the “Fake Detective” program have been held, 95 percent of the population speak Russian as a first language.

As a result, many who live in there, including teenagers, consume large amounts of Russian-language media. This can mean they are “more exposed to Russian propaganda,” Fedotkin tells me, adding that “they often rely on those sources for information.”

However, he also highlights that younger generations — many of whom have lived their entire lives in Estonia — are developing new media consumption habits.

A workshop during the “Fake Detective” program in Narva. Source: Press materials

A workshop during the “Fake Detective” program in Narva. Source: Press materials

“A lot of Russian-speaking teenagers and students in Estonia and Latvia actively use global platforms like YouTube, TikTok and Instagram, where the content is much more diverse,” Fedotkin says.

Nevertheless, “the influence of Russian media still remains strong, especially in families where Russian television is the main source of news,” Fedotkin points out, adding that even though young people often say they don’t follow political news closely, “when narratives from Russian television are constantly present at home, they can shape their subconscious view of the world.”

Family connection

Fedotkin tells me about one teenager involved in the project, who came to realize that for a long time, the main source of disinformation in his life came from within his own family.

“As a child, he believed his father’s stories about WWII and the USSR as a liberator, without realizing how selective and misleading they were.”

According to Fedotkin, the turning point came at school when a teacher presented the class with the broader context surrounding those historical events, “including uncomfortable facts that were never mentioned at home.”

Dmitri Fedotkin (second from right) with other participants of the “Fake Detective” program in Narva, Estonia. Source: Press materials

Dmitri Fedotkin (second from right) with other participants of the “Fake Detective” program in Narva, Estonia. Source: Press materials

For the young participant, “this discovery was shocking,” Fedotkin says, “but it also motivated him to start exploring educational content on YouTube and gradually develop critical thinking skills. Over time, he learned to compare information from different sources and to recognize manipulation more easily.”

New technology

Debunking narratives spread through traditional media forms is one thing. But in a world increasingly dominated by new technology, including AI, it’s vital to focus on the potential pitfalls of the information sources young people have actually come to trust.

“During the workshops we noticed that most of the participants — ninth graders — rely heavily on ChatGPT or similar tools to search for information and very few are familiar with local news portals,” Fedotkin explains. While this shows their curiosity, he says, it also highlights their vulnerability to being provided with disinformation.

“On the one hand, they are open to new technologies but on the other, they often lack the habit of checking reliable journalistic sources,” Fedotkin points out.

During the “Fake Detective” workshops, “there were, of course, some students who were more attentive and tried to analyze information more carefully,” Fedotkin explains, adding that “these observations became part of their creative process.”

A “Fake Detective” workshop in Narva. Source: Fake Detective

A “Fake Detective” workshop in Narva. Source: Fake Detective

The animations they went on to produce thus “highlighted the risks of trusting a single source and showed how important it is to pause, question and verify before drawing conclusions.”

Crucial stage

Arming Estonia and Latvia’s young Russian-speakers with the knowledge needed to fight back against disinformation is no easy task.

It’s also fair to say that there are plenty of misleading narratives out there about what remains an easily misunderstood section of Estonian society. This makes it even more important to foster engagement through projects that acknowledge the challenges faced while also encouraging creative solutions to emerge from those who those issues impact most.

As Fedotkin points out, the young people participating in the “Fake Detective” project are at a crucial point in their development “where they are still developing their critical thinking and media literacy skills.”

The “Fake Detective” project’s biggest success so far, he says, is the creation of ready-made lesson plans and materials that not only help young people build these essential skills, but also support the teachers guiding them.

“Fake Detective” also includes workshops for Russian-speaking youth in Latvia. Source: Fake Detective

“Fake Detective” also includes workshops for Russian-speaking youth in Latvia. Source: Fake Detective

“The next steps are to share these materials with others and look back at what we have achieved,” Fedotkin says. “This will help us decide if we should try to do a new project in the future with a different focus.”

Projects like “Fake Detective” won’t make disinformation — or the problems it causes — disappear overnight. But they do provide young Russian-speakers in Estonia and Latvia with valuable tools to question the world around them and foster the creativity that will help them push back.

***

All the videos and learning materials created during the “Fake Detective” project are now freely available online in English, Latvian, Estonian and Russian here.

—