On September 6, after months of litigation against the Trump administration, a federal judge ruled that Venezuelan immigrants could renew their Temporary Protected Status (TPS) in the United States. However, after the ruling was handed down, only about 20 people gathered to celebrate outside the Arepazo restaurant in Doral, Florida — a focal point of the largest Venezuelan enclave in the country.

“Under normal circumstances, you would have seen 2,000 people here at Arepazo. When [former Venezuela president Hugo] Chávez died [in 2013], 2,500 came and blocked the streets. This shows that people — despite the judge’s decision — aren’t so sure. They say, ‘I’d rather stay home; I’m not going to risk being caught by the police and thrown out of the country.’ There’s fear,” says José Antonio Colina, president of Venezuelans Persecuted in Political Exile (VEPPEX). He speaks with EL PAÍS while sipping coffee at the restaurant, the only one in the area with a statue of Simón Bolívar.

In recent months, the Venezuelan diaspora has seen how the government they once supported appears to have abandoned them. The Trump administration has tried to strip them of Temporary Protected Status and has canceled humanitarian immigration programs that allowed hundreds of thousands to live and work legally in the country. U.S. authorities are detaining asylum seekers in immigration courts, while the official narrative associating Venezuelans with the Tren de Aragua criminal organization is stigmatizing them.

At the same time, President Trump has gone on a war footing against the Nicolás Maduro regime: he has sent warships to the edge of Venezuelan territorial waters and has raised tensions with Caracas to their highest point in years. In the current context, Venezuelans in the United States are presented simultaneously as victims of Chavismo — the political movement that has governed Venezuela since Chávez’s rise to the presidency in 1999 — and as criminals on American soil.

In Doral — a city that’s about 25 miles northwest of Miami — one in three people is of Venezuelan origin. And Trump’s immigration policy has been a tough pill to swallow. The majority of voters in the young city are affiliated with the Republican Party, according to figures from the Miami-Dade County Supervisor of Elections Office.

Many residents sponsored relatives under the Biden administration’s programs. Some beneficiaries have had to leave the country, or are hiding for fear of arrest. Others have been in the U.S. for decades and have been politically active against Maduro’s regime, which would expose them to a serious risk of persecution or retaliation if deported. And all watch in bewilderment as the Trump administration deploys destroyers to combat drug trafficking off the coast of Venezuela — a country that it deems as being safe to return to.

José Antonio Colina in Miami, Florida.Eva Marie UZCATEGUI

José Antonio Colina in Miami, Florida.Eva Marie UZCATEGUI

“It’s completely traumatic. It’s one thing to search for undocumented immigrants and another thing to place people in a situation in which they’re not in the country legally,” Colina says. “They’re not seeing us as a community affected by political problems, but as a number of migrants who could be deported to fulfill an electoral promise. The Venezuelan community that voted for Trump voted to remove Maduro from power, not to remove Venezuelans from the United States.”

TPS allows people from countries facing exceptional circumstances — such as natural disasters or humanitarian crises — to live and work legally in the United States. It must be renewed every 18 months. Some 250,000 Venezuelans received TPS in 2021 — including Colina — after years of advocacy to protect those who had fled the Maduro regime and were unable to return, while their asylum cases trickled through immigration courts.

Another 350,000 Venezuelans were granted protection in 2023, when the United States concluded that “extraordinary conditions” persisted in Venezuela and redesignated the country’s citizens as being eligible for TPS. Before leaving office, former president Joe Biden extended TPS until 2026, but in January of 2025, the Trump administration reversed this measure. Immigrant rights groups sued, sparking a legal battle against the government.

Federal Judge Edward Chen blocked the measure this past March. Subsequently, in May, the government asked the Supreme Court to intervene. The court said the government had the authority to terminate TPS, but didn’t suspend the litigation or Chen’s case. In early September, Chen ruled that the government’s move to eliminate TPS was unlawful.

DHS Deputy Secretary Tricia McLaughlin argued in an email to EL PAÍS that TPS “was never intended as a de-facto amnesty program” and that “the Biden administration exploited TPS programs to allow poorly-vetted migrants to gain entry into the country, from MS-13 gang members to known terrorists and murderers.” Paradoxically, however, the State Department warns its citizens against traveling to Venezuela due to the “high risk” of insecurity, such as arbitrary detentions, terrorism, and kidnappings, as well as civil unrest and crime.

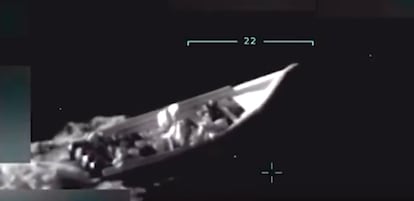

The moment the United States Armed Forces attacked a Venezuelan boat.

The moment the United States Armed Forces attacked a Venezuelan boat.

Johanna is a Venezuelan citizen who came to the U.S. in 2021. She asks that EL PAÍS not reveal her identity, for fear of retaliation from immigration authorities. She tells this newspaper that she has experienced the unrest surrounding TPS in court with anguish. And, even though she applied for the extension, she has lost faith in the system. “We’ll have to see if the government will respect the judge’s decision,” she sighs. She says that, in Doral — where she works as a waitress in a restaurant — there’s a lot of fear. When she drives with her eight-year-old son, the boy looks out the window looking for police officers to warn her, for fear of being stopped.

Following the judge’s ruling, many rushed to renew their TPS before the deadline expired on Wednesday, September 10. However, the website wasn’t allowing the process, causing confusion and panic. On Friday, September 12, the same federal judge ruled that the renewal service must be reestablished.

Judge Chen’s recent decisions have taken many by surprise. “Lots of people have already left the country,” Isamar Torres points out, because they were disappointed or pessimistic. A 35-year-old Venezuelan who arrived in the United States in 2016, she owns a form-preparation business in Doral. She believes the government is trying to “clean up” what the previous administration did.

“They want to find every person — regardless of nationality — and remove them. Their problem is that Venezuelans have TPS, meaning that they cannot be deported,” Torres adds. Many of those who entered through the land border “weren’t given due process, because so many people were transiting.” Thus, she affirms, “many criminals entered. Because it’s no secret that Nicolás Maduro’s regime opened all the prisons.” She repeats an argument that Trump has made numerous times, without evidence.

Torres indicates that most of the TPS renewals that her business has put together recently are “from 2021, from people who have been here for many years.” Some have multiple ongoing immigration processes, including asylum applications, so they “waited until the last minute” to renew their TPS. However, some have chosen to leave the U.S.

On Wednesday, September 10, she met a client who had a ticket to return to Venezuela that Friday. “He says he’s afraid and prefers to leave before being deported. He’s a decent person; he paid his taxes on time every year he’s been here. He’s never even had a fine,” Torres says.

Isamar Torres pictured in Florida on September 10, 2025.Eva Marie UZCATEGUI

Isamar Torres pictured in Florida on September 10, 2025.Eva Marie UZCATEGUI

That’s what 22-year-old Bárbara Reyes did, returning to Venezuela on April 7, 2025, the same day her TPS expired. Her aunt — a resident of Doral — had sponsored her under the humanitarian parole program. The young woman had spent two years in the United States, during which she spent a lot of time working. But she wasn’t able to study.

“I was trying to process the paperwork to study, but it seemed more and more difficult without permanent residency,” she tells EL PAÍS by phone from Caracas. She wanted to enroll at Miami Dade College, but because of her status, she couldn’t receive the in-state discount, which Florida discontinued in March of this year. “With the pressure of Trump coming and starting with the ‘I’m going to kick everyone out’ speech, I said, ‘I don’t want to give all I’ve got to one place just so they can kick me out.’”

Colina says that “criminals came in through the border, but so did good people,” including activists he knows who were imprisoned in Venezuela, as well as former officials “who refused to repress [the population].”

“But unfortunately,” he adds, “this administration doesn’t differentiate between the two. It seems that, in some ways, [for them], Venezuela is politically unstable, but in others, it isn’t.”

The Department of Homeland Security argues that it’s not in the national interest to keep these people in the country, claiming that conditions in Venezuela have improved enough for them to return. But in recent weeks, U.S. ships, warplanes and a nuclear submarine have positioned themselves near the coast of the Caribbean nation, generating tensions. This has led Nicolás Maduro’s regime to mobilize its troops in response.

Colina says that there’s hope among the public that “if they’re removing TPS and are in this operational deployment in the Caribbean, it’s because [the U.S. government] is going to remove Nicolás Maduro from power.” However, while it seems like a “somewhat excessive” deployment to combat drug trafficking, it doesn’t seem sufficient “for an invasion.” Reports indicate that there are currently about 4,500 U.S. troops in the Caribbean.

He finds it contradictory that the government wants to remove TPS under these conditions. “Maduro is still there,” he notes. He also doesn’t believe there’s a plan in place, nor a political opposition that’s ready for a transition of power. “It’s not just about removing TPS and removing Maduro. What about the transition?” he wonders.

Mariana Torrellas, pictured in Doral, Florida, on September 10, 2025.Eva Marie UZCATEGUI

Mariana Torrellas, pictured in Doral, Florida, on September 10, 2025.Eva Marie UZCATEGUI

Mariana Torrellas — the owner of a jewelry business in Doral — sponsored two relatives under the Humanitarian Parole program. She and her husband arrived in the US 10 years ago with their two children. They’re very grateful for the stability they enjoy. She’s Catholic and joined a foundation called Virgen de Coromoto to help the community.

After the social unrest that began in Venezuela in 2014 — which left dozens dead and thousands injured and detained — she saw her fellow Venezuelans arrive, fleeing with nothing but the clothes on their backs. “We helped them with food, furniture and temporary accommodation while they settled in, because there were people sleeping in the Walmart parking lot,” she recalls. She says that her country has always been supportive and welcoming of immigrants, regardless of where they come from. An estimated seven million Venezuelans have left their country as a result of the crisis.

DHS said in an email that those “whose TPS or parole status has expired — or who are otherwise in the country illegally — should take advantage of the CBP Home self-deportation process,” which supposedly gives migrants a free ticket and $1,000.

Torrellas says it’s not that simple. She knows some folks who have returned to Venezuela — especially young people, including the relatives she sponsored — but there are others who don’t have that option. “Especially families with children,” she emphasizes.

Helene Villalonga — president of the Multicultural Association of Activists, Voice and Expression (AMAVEX) — says that the recent court ruling has been “a respite” for thousands of families who “have lived in uncertainty for years.” However, she vows that they will “continue fighting for a permanent solution.”

“TPS is a relief,” she acknowledges, “but it’s not the final goal: we need a path to residency.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition