In last week’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) meeting, rate-setters sent some strong wait-and-see signals: the base rate was kept on hold at 4 per cent and the language was cautious. The committee stressed that “monetary easing is not on a preset path”, implying that the Bank of England (BoE) won’t necessarily keep up its pattern of one cut per quarter.

But the MPC did make one conclusive move: voting to slow the pace of quantitative tightening (QT) from £100bn to £70bn next year. This means that by next September, the stock of government bonds held by the BoE will have fallen from £558bn to £488bn – down from a peak of almost £900bn in 2021.

Back then, markets were nervous about QT. Naturally so – quantitative easing (QE) had buoyed markets, and it seemed reasonable to worry that reversing it might disrupt them. More recently, it has been difficult to reconcile QT (which tightens monetary policy) with interest rate cuts (which loosen it). But the MPC thinks that QT has only had a modest impact and was unlikely to have made a “material difference to the appropriate path for Bank rate over the past year”. This begs an interesting question: if things are going so smoothly, why the change of pace?

Last week, rate-setters noted that term premia on long-term government bonds had risen, both in the UK and elsewhere. In times of high uncertainty, investors demand extra compensation for holding a long-term bond, rather than a series of shorter-dated securities. The BoE also flagged more UK-specific bond market problems, including structural changes to demand. The MPC concluded that “although the UK gilt market had continued to function in an orderly manner, these factors could pose a risk that QT would have a greater impact on market functioning than previously”.

What does this mean for bond markets?

QT comes in two forms: active (where bonds are sold by the central bank) and passive (where bonds mature and the BoE doesn’t replace them). Last year, passive QT did most of the legwork, with active sales making up just £13bn of the total £100bn reduction. But over the next 12 months, fewer bonds are due to mature. Analysts calculated that maintaining the same pace would have resulted in £50bn of ‘active’ tightening: a huge amount for sensitive bond markets to absorb.

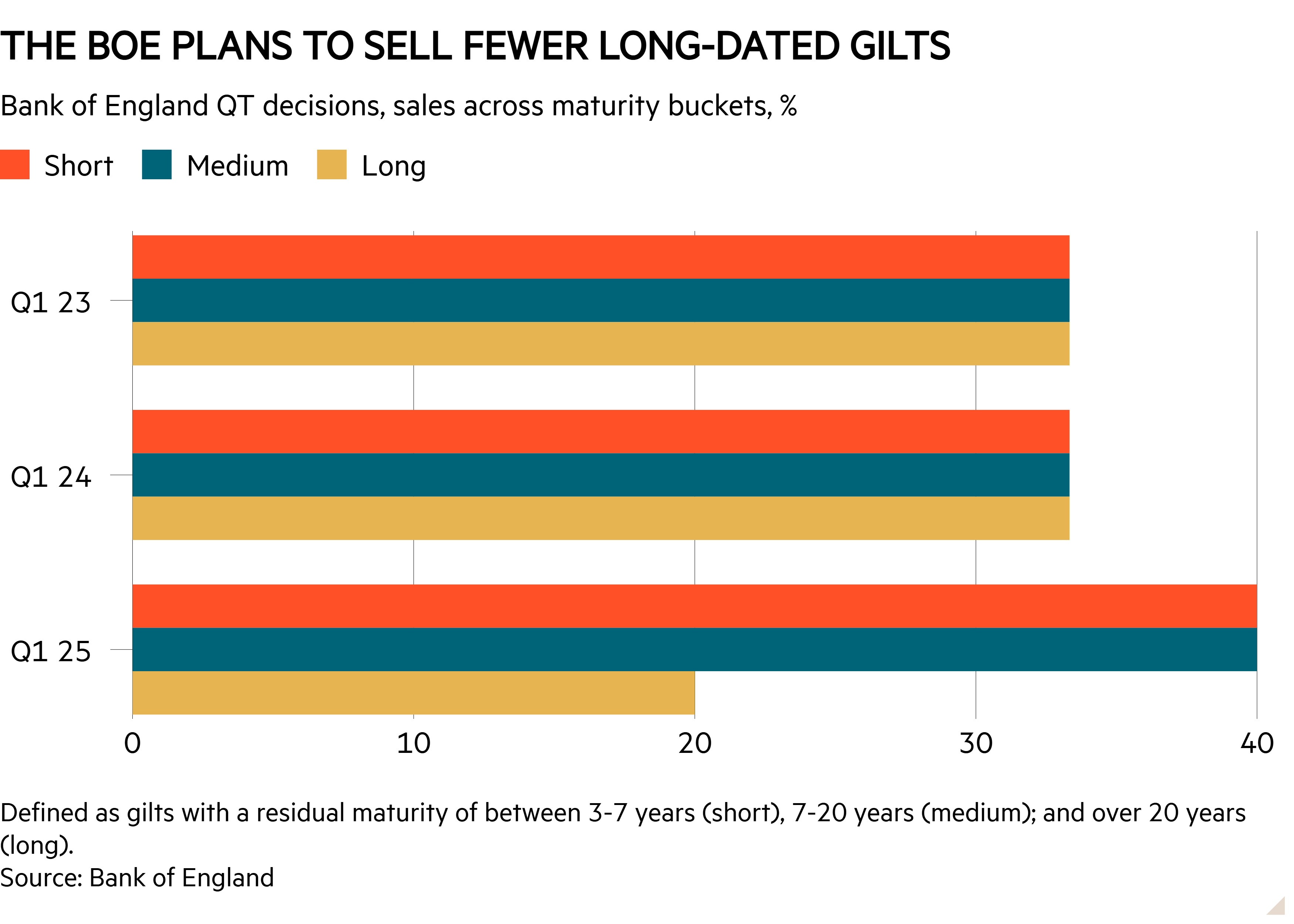

Thanks to the new slower pace, active sales will ‘only’ total £21bn over the next 12 months, although this is still £8bn more than last year. To mitigate disturbance to the bond market, the BoE is planning to sell a larger proportion of bonds with short remaining maturities, instead of equally weighting across maturities as it has done in previous years, as the chart below shows.

But analysts are sceptical. Economists at BNP Paribas still expect £4bn of active sales of long-dated bonds over the next 12 months – about the same as last year. It is also worth noting the two dissenters on the MPC. Chief economist Huw Pill favoured keeping the pace of QT at £100bn a year in the name of consistency. Catherine Mann (traditionally a hawk on the committee) favoured slowing the pace to £62bn, which would have kept active sales unchanged at £13bn.

What does this mean for the Budget?

The BoE’s decision will also impact the chancellor, since gains and losses from QE or QT are passed on to the Treasury. The BoE bought the bonds in its portfolio when interest rates were much lower, and is forced to sell them at a loss today. By slowing the pace of active QT, the BoE can limit these losses, which should boost the chancellor’s headroom by a few billion pounds.

It might sound like an easy win, but the move delays pain, rather than eliminating it completely. Holding these bonds means that the BoE pays banks more interest on reserves than it makes in coupon payments over the next few years. Analysts at Berenberg think that this could add up to £4bn in extra interest rate costs in 2029-30. This timing matters when it comes to meeting fiscal rules. The government is not judged on whether it is hitting its targets today, but on its performance at the end of a ‘forecast period’ – which is exactly when these higher costs will hit.

Either way, the near-term impact of this change will probably be overshadowed by bigger problems. Economists also expect the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) to downgrade its productivity growth assumptions for the UK economy this autumn. This could raise the deficit by £20bn in 2029-30, essentially eroding almost all of the savings from last year’s employer national insurance increase. The impact of QT tweaks looks rather marginal in comparison.