Levent Kenez/Stockholm

A research paper published by a journal linked to Turkey’s military has reignited debate over Ankara’s role in NATO, warning that the country carries heavy frontline responsibilities while enjoying limited influence in alliance decision-making.

The article, appearing in the Journal of Defence and Security Research and authored by Mehmet Kılıç of Başkent University, points to a paradox at the heart of NATO’s evolving defense posture. Turkey is described as an indispensable southern flank state with assets ranging from drone fleets to Black Sea control, yet remains structurally sidelined when strategy is set.

The journal is overseen by Turkey’s National Defense University, created in 2016 after a coup attempt that led to a sweeping purge of pro-NATO officers and the closure of traditional military academies. Built as part of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s overhaul of the armed forces, the university has since become the sole gatekeeper of officer training, giving its publications unusual weight as a reflection of how the restructured military establishment views the alliance.

The 29-page analysis surveys NATO’s 2023–2025 regional defense plans including the “East Shield” deployments along Poland, Romania and Turkey, Black Sea forward basing and the Europe-wide Sky Shield air and missile defense initiative. In each Ankara is cast as a crucial player, providing bases, logistics and enforcement of the Montreux Convention, which regulates naval access to the straits linking the Mediterranean and the Black Sea.

Turkey’s domestic defense industry, particularly its armed drone programs, is singled out as a pillar of NATO’s southern flank operations. Turkish airfields and ports are described as strategic depth for alliance missions stretching from Eastern Europe to the Middle East.

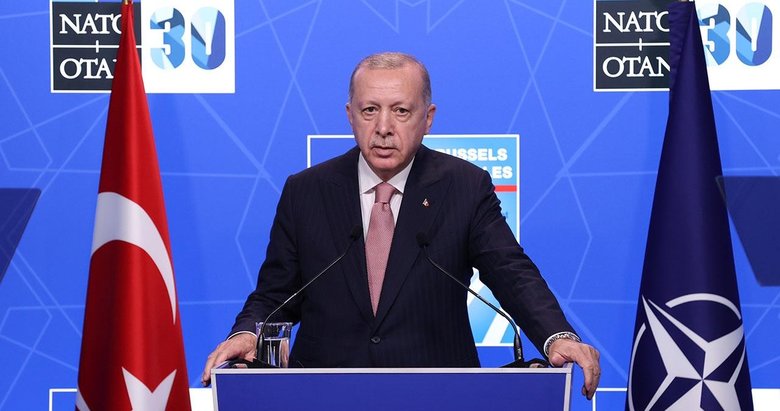

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan

But despite these contributions, the report criticizes what it calls a “high responsibility, low influence” imbalance. Decision-making power, it argues, is concentrated among core NATO states — the United States, Britain, Germany and France — while front-line allies like Turkey, Poland and the Baltic states carry disproportionate risks without an equivalent say.

That imbalance, the study warns, could deepen the alliance’s internal divides at a time when NATO is repositioning itself as not just a defense pact but a regional order-shaping actor.

The article frames Turkey as a “semi-peripheral” member: militarily indispensable but normatively and institutionally marginalized. In plain terms Ankara bears the burdens of geography and military contribution, but its voice in shaping alliance doctrine remains muted.

The critique comes as NATO pursues costly modernization efforts. Leaders at the 2025 Hague summit pledged to raise defense spending to 5 percent of gross domestic product, a target likely to strain countries already carrying heavy operational loads. For Turkey, with its volatile economy, the pressure could be particularly acute.

Since its reorganization, Turkey’s military has taken on a different profile inside NATO. Once known for its large conscript army, it has invested heavily in drones, asymmetric capabilities and rapid deployment forces. Its interventions in Syria, Libya and the South Caucasus showcased both new capacities and a willingness to act independently of allies.

That independent streak has at times rattled NATO partners. Ankara’s purchase of Russia’s S-400 missile defense system in 2019 led to US sanctions and Turkey’s removal from the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter program. Disagreements over Syria and the eastern Mediterranean have added to frictions. Yet the alliance has also leaned on Turkey’s assets, particularly in securing the Black Sea after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

The publication of the article coincided with President Erdogan’s September 25 visit to the White House. Turkish media reported that Erdogan and US President Donald Trump discussed lifting sanctions on Turkey, reinstating Ankara in the F-35 program and approving new F-16 sales. The meeting was described as positive, though no concrete decisions on the defense industry were announced. Speaking to reporters afterward, Trump said there was something President Erdogan needs to do for Turkey to rejoin the F-35 program but did not provide details. According to Turkish media, experts say that Trump’s demand could involve Ankara having to get rid of the S-400s or, as previously appeared in the media, storing them at Incirlik Air Base in Adana, as well as refraining from purchasing oil from Russia. Any move on sanctions relief or fighter jet sales would also require approval from the US Congress.

The journal article echoes long-running Turkish complaints about burden-sharing and recognition. It argues that NATO’s technological transformation, with core members driving initiatives on artificial intelligence, cyber warfare and autonomous systems, risks leaving peripheral allies as implementers rather than shapers of doctrine.

It also highlights a geographic paradox: While NATO’s new defense lines in the Baltics and Eastern Europe receive strong political backing, Turkey’s southern and Black Sea roles are treated more as operational necessities than strategic priorities.

Text of a research paper on NATO’s evolving role, published in the Journal of Defence and Security Research on September 18, 2025:

-5074855″]

The article does not suggest that Turkey should break with NATO. Instead it stresses Ankara’s indispensable role and presents the imbalance as a problem to be addressed rather than a reason to walk away. Still, by casting the issue in terms of “center and periphery,” it highlights a hierarchy within the alliance that Ankara finds increasingly uncomfortable.

Turkey, which joined NATO in 1952, fields the alliance’s second-largest military after the United States with roughly 445,000 active personnel and more than 200,000 in reserve. It hosts Incirlik Air Base, used for US and NATO operations, and the Kurecik radar station in Malatya, a key part of NATO’s ballistic missile defense shield. Turkey also provides logistics hubs and command facilities that support missions in the Balkans, the Middle East and the Black Sea, and has contributed troops to operations in Kosovo, Afghanistan and the Mediterranean. The alliance’s Land Command (LANDCOM) is based in Izmir, while Istanbul hosts the NATO Rapid Deployable Corps headquarters (NRDC-TUR). Ankara is home to NATO’s Centre of Excellence for Defence Against Terrorism (CoE-DAT) and the Partnership for Peace Training Centre, while Istanbul houses the Maritime Security Centre of Excellence (MARSEC CoE).

The 36th annual NATO summit is set to take place in Ankara on July 7-8, 2026, where heads of state and government from member countries are expected to make official decisions on security matters.

Meanwhile, Devlet Bahceli, leader of the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), a coalition partner of the government, last week said Turkey should shift its axis by forming economic and military alliances with Russia and China. However, Erdogan did not respond to this demand during his US trip, telling journalists who asked about the proposal that he was unable to follow Bahceli’s statements.