In this study, we evaluated the resilience of the Swedish health system by analysing changes in essential health services utilisation before, during and after the COVID-19 pandemic and by examining sociodemographic differences in utilisation by education and sex. All sectors that were assessed experienced initial disruptions. The analysis of service utilisation over time revealed a mixed picture: Primary care, as indicated by new prescriptions for type 2 diabetes, initially declined but recovered rapidly. Inpatient care for IBD experienced a reduction in admissions, although the duration of hospital stays remained stable. Emergency care, reflected by number of appendicitis diagnoses, showed a surprising increase in cases during the pandemic. Cancer diagnostics were significantly affected, with cervical cancer diagnoses declining markedly throughout the pandemic, while oesophageal cancer diagnoses rebounded swiftly after an initial drop. When examining sociodemographic differences, disruptions varied by education and sex but were generally not large.

The results of this study are, to some extent, supported by previous research. One study covering ten different countries assessed changes in outpatient visits, emergency room visits, inpatient admissions, surgeries and trauma admissions during the pandemic finding significant disruptions across a wide range of health services [24]. Two more in depth studies from Mexico showed that care for patients with diabetes and hypertension was severely impacted, which in turn led to a decrease in patients with these conditions under control [22].

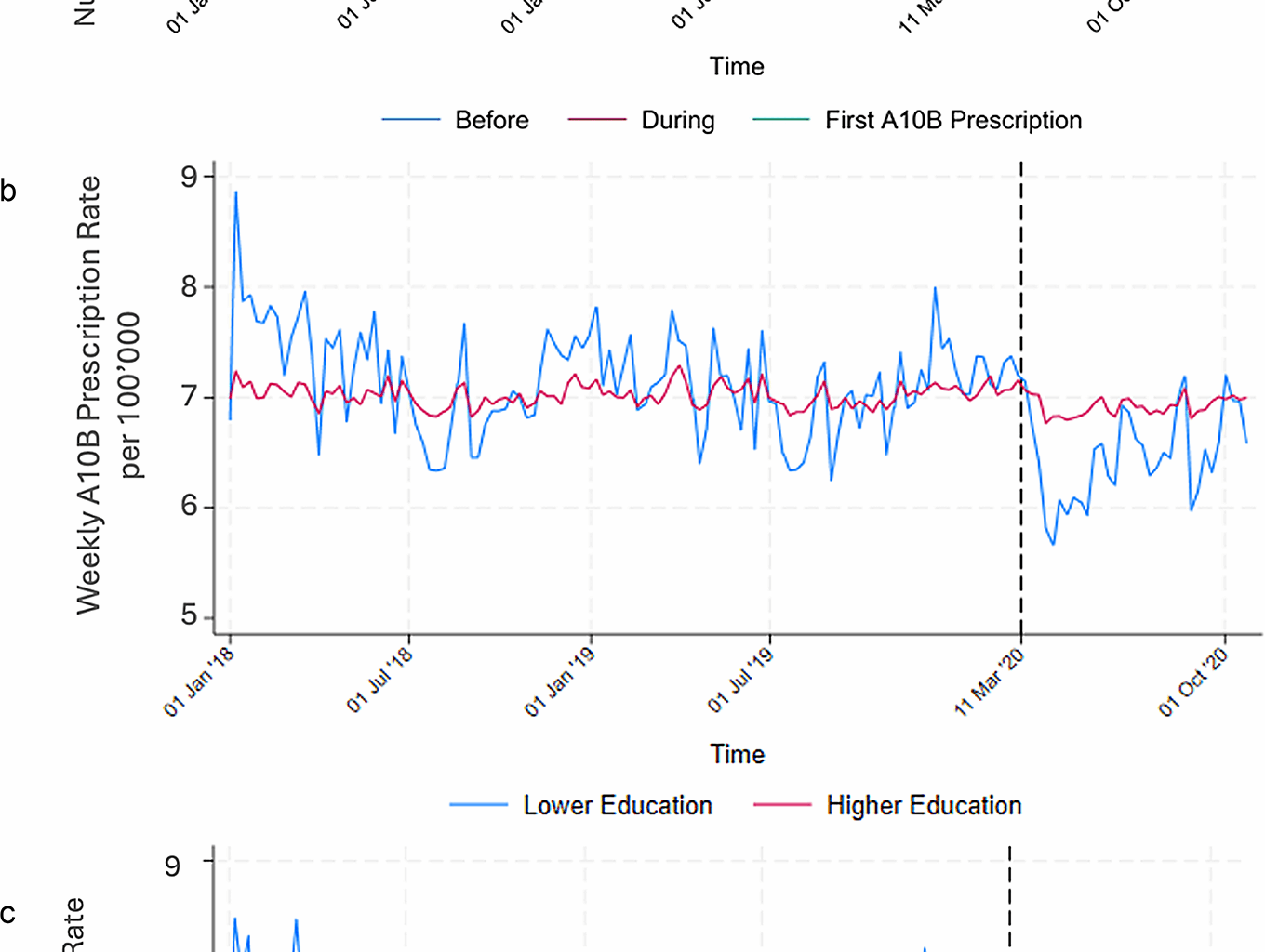

A decrease in primary care utilisation during the pandemic has been seen in several other contexts [7, 22, 24]. In terms of service utilisation over time, new prescriptions for type 2 diabetes decreased sharply at the beginning of the pandemic, but with a rapid recovery to near pre-pandemic levels. This pattern indicates that Sweden’s primary care system held up against the pandemic’s challenges. The initial drop does not necessarily indicate a failure of the health system but can rather be interpreted as its ability to adapt and adjust in times of crises and postpone non-emergency care, which is itself a form of resilience. An additional factor to consider is the role of competing risks. Excess mortality during the pandemic, particularly among older adults, may have reduced the pool of individuals at risk of developing conditions such as type 2 diabetes and might potentially partly explain the decline in new prescriptions we observed.

An analysis of sociodemographic differences revealed a more nuanced picture. When stratified by education, a more pronounced drop in primary care utilisation was observed among individuals with lower education. This could be explained by barriers such as limited access to healthcare services, lower health literacy, or financial constraints, which may in turn reduce awareness of available services, decrease the frequency of healthcare, or complicate navigation the healthcare system. By contrast, differences between men and women were small, suggesting that sex did not play a major role in primary care utilisation during the pandemic.

Inpatient care results are consistent with prior studies in the US, UK, and Germany reporting significant disruptions in inpatient care [40,41,42]. An analysis of service utilisation over time in our study showed a decrease in the number of hospital admissions for IBD during the pandemic, while the average length of hospital stays remained stable [43]. Similar disruptions were observed in Germany, where children’s hospital admissions decreased by 20% in both 2020 and 2021, In comparison, our data show smaller declines in IBD admissions. The sustained decrease in IBD admissions even after the end of the pandemic could indicate that the system failed to recover from the initial shock, or it could simply be reflecting that the system was able to adapt. One explanation might be that health care staff learned to shift some inpatient care to outpatient care during the pandemic and that this shift was appreciated by staff and / or patients and therefore sustained. Another possibility is the increased use of telemedicine, which may have enabled some IBD patients to manage their conditions without hospital admission. Improved medical therapies introduced during the pandemic might have reduced the need for surgical interventions, thereby decreasing inpatient admissions. Stricter adherence to medications or lifestyle changes by patients to avoid flare-ups, possibly motivated by a fear of contracting a COVID-19 infection in the hospital, could also have played a role. Similarly, some patients, particularly those on immunosuppressive therapies, may have avoided hospitals altogether due to concerns about COVID-19 exposure. Additionally, limited access to diagnostic services during the pandemic might have delayed the identification of IBD flare-ups or complications, contributing to fewer hospitalisations. There was no change in the length of hospitalisation for IBD patients and thus no sign of more prevalent early discharges due to pandemic pressure on health care. A few studies have shown a possible link between IBD and either COVID-19 infection itself or COVID-19 vaccinations [44,45,46], but our results do not show any indication of such a link affecting inpatient care. Another possible explanation for the drop in hospitalisations is again the role of competing risks. Some studies suggest that patients with IBD have an increased risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes and higher mortality [47]. As a result, some patients may have died earlier in the pandemic, thereby reducing the number of individuals at risk of subsequent IBD-related hospitalisations. However, this effect is likely to be smaller than the changes attributable to care adaptations and patient behaviour.

When examining sociodemographic differences, distinct patterns emerged. When stratified by education, the higher education group had a lower rate of hospitalisation, which may reflect better disease management or lower incidence of the disease in this group in general. Individuals with higher education levels may be more proactive in managing their health, leading to earlier detection of complications. The drop in cases in line with the start of the pandemic was more pronounced in the higher education group indicating that this group may have been more worried about being exposed to the virus during a hospitalisation and therefore taking further precautions to avoid hospitalisation. Despite these differences in hospitalisation rates, the length of hospitalisation for IBD remained unchanged for both groups, indicating that the severity of cases, once admitted, did not differ significantly between the education groups. Although women generally had higher admission rates for IBD than men, the pattern of decline during the pandemic was similar for both groups. This suggests that the pandemic’s effect on inpatient care utilisation was not strongly sex-dependent, but rather influenced by other factors such as education and system adaptations.

The pattern of service utilisation over time in emergency care contrasts with reports from other countries. Although there were some early indications from both Sweden and Greece that COVID-19 infection may have increased the risk of appendicitis [48, 49], other countries reported a decrease in appendicitis during the pandemic [50, 51]. In Denmark for example a nationwide study noted a decrease in the total number of appendicitis cases but a shift towards more severe cases seeking treatment [51]. Tentatively, Sweden’s non-lockdown approach, combined with a potential increased risk due to COVID-19, might have contributed to the observed increase in appendicitis diagnoses at the start of the pandemic, followed by a significant decrease at its end. Furthermore, pandemic-related stress and lifestyle changes, such as altered diets or reduced physical activity, could have contributed to a slight increase in appendicitis incidence. In countries with stricter restrictions, the pandemic may have appeared more serious, with the strict measures making the threat of the virus a more immediate reality. This likely heightened public awareness of the potential to overwhelm the healthcare system, and people might have been more cautious about seeking care for non-COVID-19 related conditions, such as appendicitis. The temporary increase in cases may be related to the rollout of COVID-19 vaccinations, which could have encouraged people to resume normal care-seeking behaviour despite the ongoing pandemic. If there is a biological mechanism at play between COVID-19 and the risk of developing appendicitis, then this means that the Swedish health system was able to adapt to the increased influx in patients, therefore, indicating that emergency care in Sweden managed to uphold utilisation of health services during the pandemic. An analysis of sociodemographic differences was limited to sex, as education was not included for this indicator due to the high proportion of minor patients. For the available data, the higher incidence of appendicitis among men compared to women was consistent throughout the study period, which is in line with the current literature on the topic [52], indicating that the pandemic did not alter underlying sex-related differences in disease occurrence or care-seeking for acute conditions. However, it was beyond this study to evaluate if the quality of care was upheld.

The service utilisation over time for cervical cancer diagnostics was severely disrupted. The sharp decline in cervical cancer diagnoses due to disrupted screening services aligns with global findings of disrupted cancer care during the pandemic [22,23,24, 37, 53]. For instance, studies in Mexico reported a decrease in the number of diagnoses of cervical and breast cancer diagnoses [22, 23], a trend similarly observed in research from Romania and the Nordic countries [37, 53]. At the start of the pandemic, 13 regions in Sweden completely paused screening services and reduced them in 5 other regions [54]. However, some regions, such as Stockholm for example [55], adopted at-home screening methods in July 2020 when the National Board of Health and Welfare issued new guidelines [54]. Among the healthcare sectors analysed in this study, cervical cancer screening appears to have been most heavily affected. Planning for alternative screening methods during health crises is part of upholding the resilience of the health system [34]. Although there is a slight observable recovery in number of weekly cervical cancer diagnoses after the end of the pandemic it does not reach pre-pandemic levels. An analysis of sociodemographic differences was limited to education, as this indicator exclusively affects women. Cervical cancer diagnosis rates decreased similarly in both higher and lower education groups after the start of the pandemic, indicating that the disruptions to screening services impacted all sociodemographic groups equally.

In contrast, the service utilisation over time for oesophageal cancer diagnostics was largely stable. Diagnostics seem to not have been affected as much as cervical cancer by the pandemic. A possible explanation for this is the severe symptoms that patients with this disease usually present with, facilitating its detection even during the pandemic. An analysis of sociodemographic differences revealed subtle patterns. For oesophageal cancer, men showed a more rapid recovery in diagnoses after the initial decline compared to women, who experienced a temporary increase during mid-pandemic. These findings suggest sex-specific dynamics in diagnostic pathways. When stratified by education, a decrease in diagnoses was observed in both higher and lower education groups, with the higher education group having an overall lower incidence of cases.

Overall, disruptions to healthcare utilisation during the pandemic differed somewhat by education and sex. A more pronounced drop in type 2 diabetes diagnoses was seen in the lower education group, while IBD admissions fell more steeply in those with higher education. Sex differences, on the other hand, were smaller overall but remained visible: for example, IBD admissions were higher among women throughout, appendicitis more frequent in men, and oesophageal cancer showed slightly different recovery patterns by sex. These findings align with earlier studies suggesting social gradients in delayed care may vary depending on diagnosis and healthcare level [56, 57].

Strengths of the present study include the nationwide population-based coverage of the registers included. The data from the Swedish population-based healthcare registries is considered highly reliable and with high coverage [58, 59]. ITS analysis to evaluate changes in health service utilisation across different healthcare sectors during the pandemic was used, offering the advantage of clearly identifying temporal changes and trends influenced by the pandemic. Most of the indicators for the different parts of the health sector are based on previous literature [22, 23, 32, 33, 37, 53], making them useful for comparing with previous studies, and to get an overview of health system resilience in these sectors. While income, occupation, and education are distinct and not interchangeable indicators of SES [60], education is the most stable SES proxy in Sweden during the pandemic, especially when compared to the volatility of income and occupation during that time. Limitations of this study include incomplete data for the first A10B prescription indicator for new diagnoses of diabetes type 2 since guidelines changed, making it an unreliable indicator beyond October 2020. In addition, changes in the registry data may reflect alterations in data collection practices during the pandemic, rather than actual changes in patient care. Moreover, our classification of time periods is simplified. For example, excess mortality remained elevated during what we defined as the post-pandemic period, and the pandemic period itself encompassed both a pre-vaccine and post-vaccine phase. These differences may have influenced healthcare utilisation patterns and should be considered when interpreting the results. It should also be considered that competing risks may have influenced our findings for chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes as it is more common amongst the elderly and IBD, where excess mortality reduced the pool of individuals at risk of new diagnoses. However, this mechanism is less relevant for acute conditions such as appendicitis, which presents suddenly and typically requires immediate medical attention regardless of competing risks, or for cancer incidence, where the key influence during the pandemic was delays in screening and diagnostics rather than removal of individuals from the at-risk population. Further limitations include the selection of indicators from different sectors, as there might be other factors at play affecting the changes seen. Aggregating education into just two categories may overlook nuances between the seven distinct education groups, but this approach was adopted for simplicity in visualisation, with the cut-off point based on previous research [61]. Lastly, while using national-level data in a decentralised health system like Sweden’s may not capture regional differences in pandemic responses and outcomes, the existence of overarching national policies [62] likely contributed to uniformity in pandemic response strategies across regions.

Perhaps the most important lesson learned from the study of these indicators is how to continue cancer screening and plan ahead before the next health crisis hits. Further research is also needed to better understand whether changes in IBD admissions indicate a failure to recover from the initial shock or simply the system adapting and becoming more efficient in the aftermath of the pandemic. Additional research on potential biological mechanisms between COVID-19 and appendicitis would be valuable. If this were indeed the case, it could be relevant especially in countries that saw a decrease in appendicitis cases meaning that they missed even more cases than previously anticipated.

Exploring socioeconomic factors, such as occupation, country of birth, and income, could provide valuable insights into varying health-seeking behaviours and further clarify disparities in healthcare access and utilisation. While this study focuses specifically on Sweden, its findings may also be relevant to other countries that choose to adopt a pandemic response approach similar to Sweden’s in future crises.

Overall, the findings emphasise the importance of maintaining routine care during pandemics by adapting quickly to the initial shock to avoid long lasting effects on patients. The health system managed to a large degree cater for the diagnoses observed, independent of educational level. We highlight areas for improvement in crisis preparedness, emphasising the importance to learn from the COVID-19 pandemic to improve the health system’s resilience to be adaptable and to ensure utilisation of health services during future public health emergencies, and the need for future research.