Read: 3 min

When President Trump announced recently that the U.S. would charge companies US$100,000 to bring in workers under the H-1B visa, many Canadians spotted an opportunity.

The following weekend, Prime Minister Carney told international audiences that Canada was looking at having “a clear offering” for people in the tech sector who would have otherwise been eligible for the H-1B.

Other politicians and business leaders have voiced enthusiasm for this idea.

While formerly U.S.-destined talent may seem like too good a deal to pass on, we need to exert more discipline than shoppers circling a sale bin.

Canadians should be asking ourselves two questions: Why is the Trump administration making it costlier to bring in H-1B workers? And how does Canada solve its own more foundational problem of retaining homegrown talent?

Trump’s Sept 19 proclamation lays out the administration’s case for increasing the cost of the H-1B visa, which is used primarily by major tech and IT firms to bring in up to 85,000 new workers a year.

Drawing on data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the proclamation notes that U.S. computer science and computer engineering college graduates now face some of the highest unemployment rates in the country. The H-1B visa program may be making it even more challenging for these graduates to find jobs, the proclamation says.

It also notes that U.S. firms are hiring foreign tech workers at a discount. It points to a study by the progressive Economic Policy Institute think tank which showed a 36 per cent discount for H-1B “entry-level” positions as compared to full-time, traditional workers. The proclamation claims the program is thus detrimental to American jobs and wages and is failing to fulfill its intended purpose.

Canadian Affairs recently argued in these pages that Canada should end its Temporary Foreign Worker Program for low-skilled workers for similar reasons to those outlined in this proclamation. Does the same logic apply to high-skilled workers?

Specifically, what are the employment prospects of university graduates in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) fields? And how would the admission of more foreign talent affect wages?

We don’t have the answers to these questions. But our reporting shows that the Canadian government’s own analysis suggests we do not need foreign talent in many of the STEM fields.

In February 2025, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada updated the STEM category of its Express Entry visa program to remove 19 occupations and add six.

The 19 removed occupations included data scientists, computer engineers, software developers, mathematicians and computer systems developers. Added occupations included mechanical and geological engineers, technologists and insurance agents.

In a Sept. 22 email, an IRCC spokesperson explained the changes to Canadian Affairs as follows:

“Express Entry categories are based on labour market projections from the Canadian Occupational Projection System … In 2024, COPS was updated to reflect occupations identified as expected to face shortages over the period of 2024 to 2033, and the 2025 Express Entry categories were updated to reflect those projections.”

To say the least, this information is hard to reconcile with Carney’s rhetoric — unless he thinks Canada has a bright opportunity to scoop up the world’s best insurance agents.

Second, Canada needs longsighted, steady policymaking that responds to the challenges we know and can control.

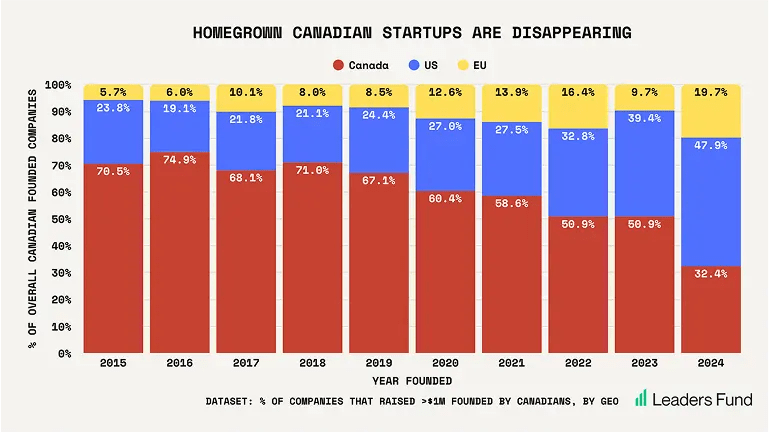

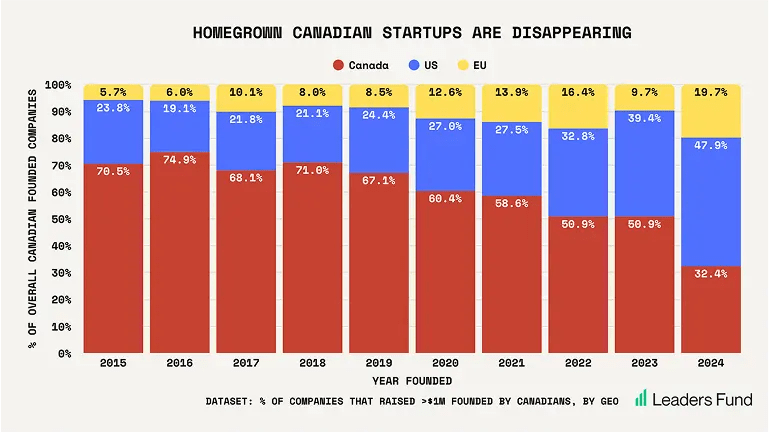

One of those challenges is the exodus of homegrown talent. Business leaders have been raising this concern for years. A new report by the Toronto venture capital firm Leaders Fund puts a point on the problem.

The report, which is based on an analysis of some 3,000 Canadian startups, shows founders are increasingly starting their companies abroad, especially in the U.S., and especially since the pandemic.

Leaders Fund chart.

Leaders Fund chart.

The report identifies several explanations for this trend. These include the ease and pace of raising large amounts of capital in the U.S., as well as different work cultures and tax incentives.

“National pride is not enough to keep founders here,” it concludes. “The only real solution is to make Canada a place where ambitious entrepreneurs believe staying is the best choice for their company and their future.”

We agree. It seems misplaced to be focusing our energies on bringing in new talent, when we haven’t solved the more fundamental problem of getting existing talent to stay.

As Carney and others make the media rounds, that is the message they should be looking to communicate — rather than rhetorically opposing a U.S. administration that has so far been no friend to Canada.

But if we learned anything from the Trudeau government, it is that we not only need a good message, we need a good plan.

Related Posts