This research demonstrated that the application of different methods to measure social vulnerability can lead to different social vulnerability rankings, even when using identical underlying data. By comparing the INFORM and SoVI methods in Burkina Faso, a country facing multiple natural and man-made disasters, we revealed significant inconsistencies in vulnerability assessments that have direct implications for humanitarian assistance allocation.

This finding raises concerns about the reliability and validity of current assessment methods. The INFORM index is promoted by UNDP and the EU’s Joint Research Center as a tool to “help make decisions at different stages of the disaster management cycle, specifically climate adaptation and disaster prevention, preparedness and response”35. Similarly, the SoVI approach has become influential in academic research and increasingly in policy applications.

When these popular methods produce different rankings of vulnerable communities, the underlying methodological choices or potential biases may influence decisions, and therefore the provision of assistance to the most vulnerable communities. Given the increasing reliance on data-driven or even automated decision-making in humanitarian contexts36, the stark differences make it crucial to increase transparency regarding the underlying methodological choices, and to analyse how it comes that different methods result in different outcomes (such as different rankings) even when using the same input data.

Both indexes are compensatory in nature, assuming that poor performance in one indicator can be offset by good performance in another. As Figs. 2 and 4 show, however, the underlying assumptions are questionable. For instance, does access to television and more information enable a commune to cope with an influx of IDPs? Does access to more water points help cope with conflict? Especially additive vulnerability frameworks that have their root in multi-attribute utility functions have been shown to generate composite indicators with higher compensability of attribute components. Multiplicative forms can be used to ensure that a low score in one component reduces the composite indicator drastically37. These methodological choices have significant implications that are rarely made explicit to end-users. Yet, our findings show that it is advisable to reflect on the underlying aggregation mechanism, and explore alternative aggregation methods, or develop methods to capture the non-compensurability of certain indicators, e.g., via taboo trade-offs, (situations where comparing sacred values like human life with secular values like economic costs is considered morally problematic, see e.g.,38.

For humanitarian and development actors guided by principles of neutrality and impartiality, it is essential that vulnerability assessment methods identify those most in need without introducing biases. Contextualised transparency39 in decision-making (whether automated or not) is important for accountability both towards donours and populations affected. As a starting point towards accountability and methodological transparency, we discuss the methodological benefits and drawbacks encountered during the analysis of our case study and in the literature. We will discuss the 1. indicator selection 2. dynamic behaviour both spatially and 3. temporally suitability for humanitarian decision-making of the two methods. We summarise and synthesise our findings on all categories in Table 1.

The statement “garbage in, garbage out” often used in modeling, also holds true in the development of social vulnerability indices. It emphasises the importance of including accurate and relevant indicators that truly reflect the factors shaping social vulnerability. In the case of the inductive approach, a larger pool of indicators is typically used by an automated method (PCA) to select the indicators that explain the most variance. While this approach accounts for the double counting of correlated indicators, it provides limited opportunity to reflect upon the meaning of indicators or PCs within their context. Normative choices are hidden and are therefore more difficult, especially for the less data and model-literate users, to be challenged or adjusted. For instance, in Cutter’s initial work on SoVI, migrants were considered as negative for resilience16. However, there is increasing evidence to suggest that migrants may possess significant resilience due to the challenging journeys they have undertaken40. Moreover, it is crucial to consider broader perspectives and incorporate distributional impacts and inequality within social vulnerability assessments41.

Localisation and the need to be sensitive to different contexts are at the heart of the humanitarian agenda since the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit42. The SoVI approach automatically accounts for the different situations in different countries (or different years): depending on the data (and the explained variance) different sets of PCs and underlying indicators may be chosen to calculate social vulnerability. However, this purely data-driven approach does not integrate the view of local decision-makers or communities and does not allow them to raise their views on how to interpret or weigh the indicators. The globally standardised INFORM-index claims to support a ’global comparison’ of different countries as the same indicators are used for each country. However, the underlying mechanisms that drive vulnerability may be very different; or different indicators may have different meanings and interpretations. To address these limitations, it is important to involve local authorities, communities, and stakeholders in the design, and interpretation of social vulnerability analyses, and to discuss potential trade-offs and choices.

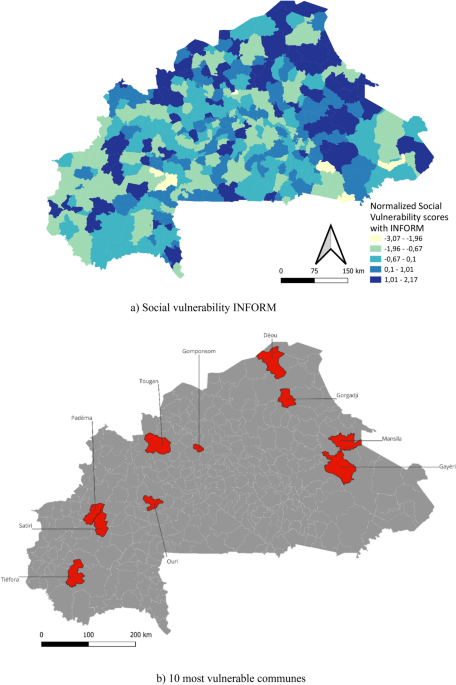

There is a broadly recognised need to understand the dynamics of social vulnerability, both in terms of spatial differentiation and temporal dynamics43. Our spatial analysis reveals that the hierarchical INFORM approach provides greater differentiation among highly vulnerable communes as compared to the SoVI approach (Supplementary Figure S5). This enhanced differentiation is particularly important for communities with higher vulnerability scores, allowing for more nuanced prioritization among the most vulnerable populations.

Our temporal analysis clearly show that social vulnerability changes over time, driven by the dynamic situation on the ground, see Fig. 5. However, the methods differ markedly in their ability to capture these temporal changes. While the INFORM method successfully tracked temporal variations, the SoVI approach could not produce meaningful temporal results in our case study due to data limitations. This highlights a fundamental challenge: despite advances in data collection through satellite imagery and other technologies, data gaps remain prevalent in many vulnerable countries. The SoVI method, being more data-intensive, requires substantial information to achieve statistically significant results-a requirement often difficult to meet in rapidly evolving crises, as in our case study on Burkina Faso.

Although increased investment in data collection and technology may eventually address some of these limitations, for both types of social vulnerability assessment, it will remain difficult in very dynamically evolving situations to rapidly recalculate social vulnerability, as these situations require data with high spatial and temporal resolution. This could include scenarios involving fast-onset natural hazards, the outbreak of violent conflict, or mass migration, where timely and accurate assessment of social vulnerability is crucial.

Throughout the paper, we investigated different ways of assessing social vulnerability. Social vulnerability assessments form an important input for decision-making. We can distinguish different decision-making processes along the disaster risk management cycle. Usually, social vulnerability assessments are used to plan and budget for prevention or preparedness (DRR) type of interventions. This can be both at the global, national or local level (across or within administrative units). In some cases, social vulnerability assessments might be used in anticipatory action and humanitarian response, especially if, for example, damage and needs assessments are not yet available. All these applications require that social vulnerability assessments are contextualised and situation-specific43, which depend heavily on the spatial and temporal resolution of available indicator data.

Drawing from concepts in explainable AI44,45, we can evaluate both methods based on their intrinsic functioning (model transparency) and post-hoc behavior (outcome analysis). In terms of intrinsic functioning, the inductive SoVI approach requires more computational time than the hierarchical INFORM approach. This might be acceptable for preparedness and mitigation when social vulnerability assessments are not used in real-time. For anticipatory action or humanitarian response, computational effort might be more important; however, the most important bottleneck at this stage is data availability. In terms of transparency, the inductive SoVI approach, though potentially more statistically robust, creates a “black box” effect where composite principal components may increase mathematical explanatory power but reduce human interpretability. This has been shown to be particularly problematic for decision-makers operating under crisis conditions with cognitive constraints46. Humanitarian organisations are, by their very mandate, committed to the principles of humanity, neutrality, impartiality, and independence. However, neither method explicitly incorporates these principles into their methodological frameworks. The statistical automation of weights and indicators in SoVI potentially obscures normative choices, while INFORM’s standardised approach may overlook crucial contextual factors. This is particularly important in situations where vulnerable populations are relying on humanitarian assistance and support. Given the differences between both approaches that we found, we suggest undertaking broad sensitivity analyses and methodological comparisons before sparse resources are allocated to ensure the robustness of the chosen approach.

In terms of post-hoc evaluations of how the model behaves, we have clearly shown the considerable differences between INFORM and SoVI. The difficulty with the post-hoc evaluation of social vulnerability is that we have no means to validate the outcome of the model behavior with actual ground-truth data and to determine whether INFORM is better representing the ground truth than SoVI or the other way around. Medina et al.47 propose combining hierarchical and PCA approaches, using PCA to screen variables before applying them in a hierarchical framework, a promising direction for more robust assessments that merits further exploration.

This exploratory study on Burkina Faso compares two prominent methods for assessing social vulnerability, Cutter’s Social Vulnerability Index as an inductive method and the JRC’s INFORM as a hierarchical method. While our findings clearly demonstrate significant variations in vulnerability rankings between these two methods, we acknowledge that the generalisability of these results is constrained by our single-case design and the specific context of Burkina Faso. Burkina Faso represents a particularly dynamic context subject to large fluctuations in vulnerability factors due to overlapping crises of conflict, displacement, and natural hazards. Different countries with varying hazard profiles, data availability, and socioeconomic conditions might exhibit different patterns of methodological divergence, and the ranking differences we observed might not be as extreme in more stable contexts. Further, while we chose Cutter’s SoVI and the INFORM index as two prominent assessment methods, we acknowledge that there is a variety of different approaches to assessing and quantifying social vulnerability. We therefore encourage further comparative studies that encompass diverse contexts and include a broader range of assessment methods.

Rather than providing conclusions about the universal superiority of any method, our research thus aims to initiate a critical discussion about the implications of methodological choices in vulnerability assessment. We encourage similar comparative analyses across diverse geographical and socioeconomic contexts to build a more comprehensive understanding of when and how methodological differences manifest. This broader investigation would help determine whether the discrepancies we observed are unique to Burkina Faso or represent a systematic issue in vulnerability assessment. By highlighting methodological sensitivities in Burkina Faso, we hope to stimulate more extensive cross-contextual research and methodological refinement to strengthen vulnerability assessment practices globally.

Further, the duration and scope of the study may also limit our findings, especially in terms of data availability. When we conducted the study, in 2022, the data available for Burkina Faso was still limited. As data collection efforts continue and improve, it is possible that more comprehensive data will become available, enabling broader comparison and temporal analyses using the inductive PCA-based method.

In addition, we acknowledge that while quantitative measures provide valuable insights into social vulnerability, they often lack the nuanced understanding of local contexts and the perspectives of those directly involved in the decision-making processes. We have clearly shown that the different approaches lead to different results and rankings. However, there remains the issue of a lacking ’ground truth’ that makes it possible to decide why and how to prioritise certain indicators, or how to avoid that potential critical factors being overlooked. While the study’s comparison provides valuable insights into the comparative performance of these methods in Burkina Faso, by engaging decision-makers in interviews, insights can be gained into priorities and considerations involved in addressing social vulnerability assessments, particularly for indicator selection, debiasing, and explainability.

In sum, our findings speak directly to the needs of both researchers and practitioners. For researchers, we contribute to the methodological discourse on social vulnerability. For practitioners who use vulnerability assessments to guide resource allocation and program design, our results stress the importance of critically examining the methodological foundations of the tools they employ. When different methods result in substantially different vulnerability rankings despite relying on identical data – as we have demonstrated in Burkina Faso – decision-makers must carefully consider how their methodological choices might inadvertently influence which communities receive assistance.

This observation calls for a collaborative approach that brings together researchers, practitioners, and – crucially – local communities who have vital contextual knowledge. This collaboration could take different forms such as co-design workshops where vulnerability frameworks are collectively developed, participatory validation processes where communities evaluate and interpret assessment results, and knowledge exchange platforms where methodological innovations are tested against local realities. By integrating local expertise and lived experience, vulnerability assessments can become more scientifically rigorous and more contextually relevant. In addition, this approach may also enhance the legitimacy, acceptability, and access to vulnerability assessments among the populations they aim to serve.