Many Canadians experienced decidedly un-fall-like weather last weekend, with temperatures soaring into the mid to high 20s across many parts of the country, well above seasonal averages.

People flocked to beaches in Toronto and Ottawa, an unlikely sight for the beginning of October, as the nation’s capital broke a heat record, reaching 29.9 C on Sunday. Montreal also reached 29.9 C on Sunday, also breaking a record.

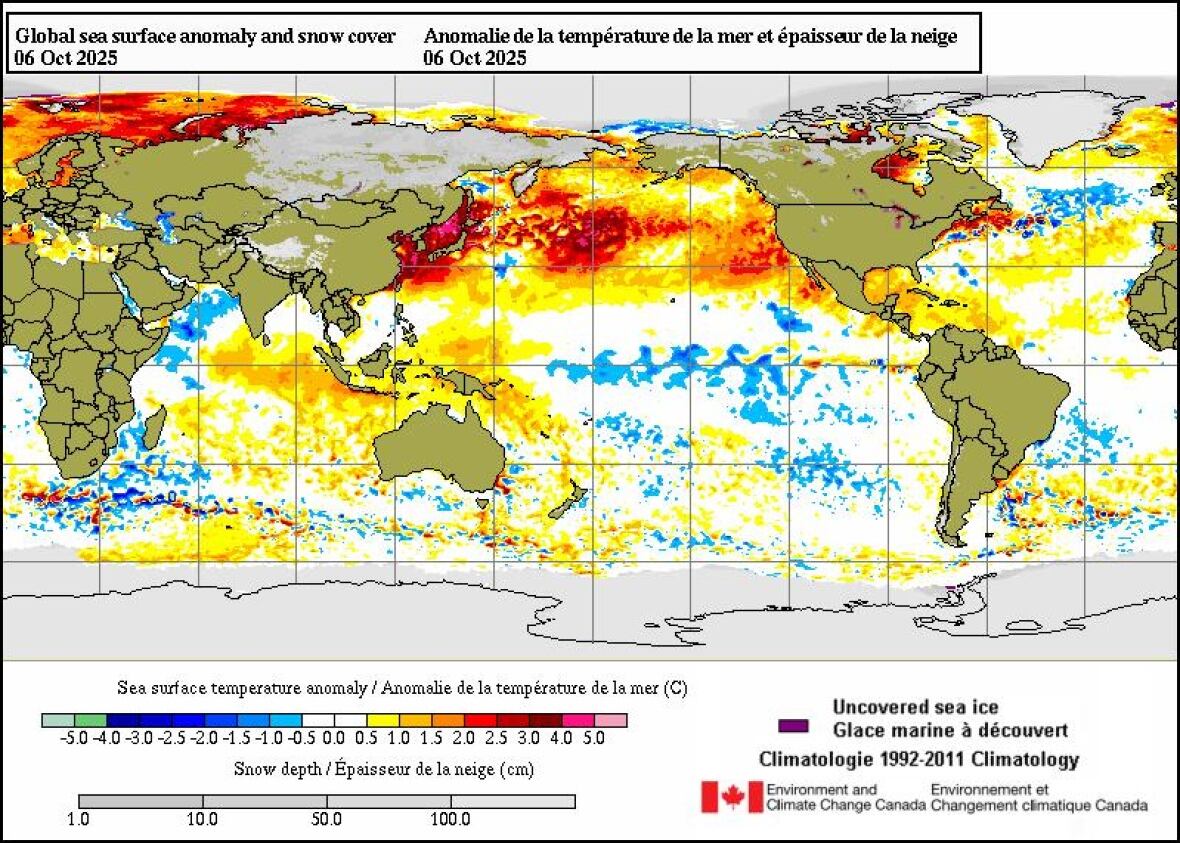

Why is it so warm? Experts point to a massive heatwave in the northern Pacific Ocean as one of the likely culprits.

The unusually warm ocean temperatures are pushing the jet stream north, says Lualawi Mareshet Admasu, an atmospheric scientist at the University of British Columbia.

The jet stream is a narrow band air that flows quickly, west-east, over the Northern Hemisphere, acting as a boundary between colder air in the north and warm air in the south. Scientists are still figuring out the complex link between ocean heatwaves and the jet stream, but as it shifts north, parts of Canada have felt “very warm air from southern or Equatorial regions,” he said.

A large and unusually warm area of water in the northern Pacific Ocean on Monday is shown in this graphic from Environment and Climate Change Canada. (Environment and Climate Change Canda)

“Some temperature records were broken by over five degrees,” said Geoff Coulson, a warning preparedness meteorologist at Environment and Climate Change Canada.

“That is a very rare occurrence,” he said, as records are typically broken by “a fraction of a degree, or maybe a degree or two at most.”

With a temperature record for this time of year broken, many took advantage of what feels like an extended summer — although not everyone was so warm on the weather.

The current marine heatwave is similar to the so-called “blob,” a multi-year band of warm water that, from 2013, significantly affected marine life and fisheries off the U.S. and Canadian west coasts.

Studies have shown that marine heatwaves are being made worse and more frequent by global warming, says William Cheung, director of the Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries at the University of British Columbia. Since the “blob” there have been marine heatwaves every year since 2019.

That means “we would be seeing more frequent and more intense heatwaves happening as we move forward, if we don’t do a good job of mitigating climate change,” he said.

The ocean absorbs about 90 per cent of the atmosphere’s excess heat, which continues to warm because of greenhouse gas emissions from the burning of fossil fuels. Temperatures in the northern Pacific this year are nearly 2.5 degrees warmer than the pre-industrial average, which is likely not a short-term fluctuation, according to an analysis from the scientific group Berkeley Earth.

A dog wears tinted goggles while being walked along Dow’s Lake in Ottawa on July 28, when temperatures hit 33 C. (Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press)

Previous marine heatwaves had devastating impacts on local fisheries. The Pacific cod fishery off the coast of Alaska had to be closed in 2020 due to low numbers. The entire Bering snow crab fishery — worth over $200 million US per year — collapsed abruptly in 2018-19 after its numbers fell 90 per cent.

“Many people are dependent on the ocean directly for food, for culture, for livelihood,” Cheung said.

“At the same time, through the changes in weather systems [the marine heat] affects, it also affects people in a more indirect way.”

Meanwhile, on land, the forecast shows temperatures returning closer to seasonal normals this week as a cold front moves through Ontario and Quebec. But Admasu says researchers like him will be watching the Pacific heatwave, which is not letting up.

“The ocean changes at slower time scales than the atmosphere itself. So generally when you have these these impacts, they tend to stay or persist for some time,” he said, adding that he expects a warmer than usual fall in North America overall.