The latest technologies are presenting Arab and North African states with a whole new set of struggles and opportunities. Morocco is a case in point.

Morocco’s Minister of Digital Transition, Amal El Fallah Seghrouchni, attends the second day of the Web Summit in Lisbon, Portugal, on Nov. 13, 2024. © Getty Images

Morocco’s Minister of Digital Transition, Amal El Fallah Seghrouchni, attends the second day of the Web Summit in Lisbon, Portugal, on Nov. 13, 2024. © Getty Images

In the Middle East and North Africa, AI is becoming a strategic priority

Morocco is promoting digital sovereignty through new initiatives

Heavy reliance on foreign technology remains a structural vulnerability

Artificial intelligence was once viewed in Morocco as a peripheral concern, the by-product of Western techno-industrial agendas dominated by global digital platforms. Initially dismissed as a domain confined to entertainment technologies, video games and smartphones, AI has progressively asserted itself as a critical technology. For Moroccan authorities, the imperative is clear: Either the country assumes sovereign control over the digital instruments shaping the new global order, or it risks marginalization.

This strategic shift began with the launch of the “Morocco Digital 2020” agenda, later revised through successive digital transition frameworks. From the outset, Rabat signaled its intention to reduce dependence on global tech conglomerates, predominantly based in North America and Asia.

The authorities’ ambition has been to foster a digital political culture aligned with local identity and traditions. The Moroccan government has taken this approach before with major global policy trends such as environmental commitments, but has struggled to translate top-down strategies into concrete economic outcomes.

Morocco’s digital sovereignty agenda has three key pillars: the development of a national cloud infrastructure, the expansion of data centers and the design of targeted support mechanisms for tech start-ups. The hope is that this will trigger a nationwide shift that will eventually lead to digital self-reliance.

However, a systemic vulnerability persists. As with several other states in the region, the Moroccan digital ecosystem remains heavily reliant on foreign technological components, including servers, software, security protocols, certifications and cloud infrastructure. These elements are largely imported, operated or manufactured by entities subject to foreign jurisdictions. The handling of sensitive data, whether administrative, economic or personal, involves external systems that offer limited guarantees in terms of confidentiality or institutional control.

A similar challenge applies to the adoption of AI algorithms developed abroad. These systems, often engineered by multinational tech firms, function as opaque black boxes. User countries exert no control over their design and cannot ensure that processed data remains under national oversight – a crucial concern for regional governments. Furthermore, these algorithms are typically trained on datasets that reflect social, legal and cultural contexts different from those of Morocco, potentially leading to misinterpretations, operational bias or discriminatory outcomes.

Balancing governance and innovation

To achieve its goals, Morocco will have to advance digital transformation and strengthen institutional governance at the same time, making sure that one does not come at the expense of the other. If technological progress outpaces institutional frameworks, authorities worry the loss of control over key digital infrastructures and tools could destabilize society. Conversely, an overly cautious or rigid governance model could hinder innovation and delay the deployment of digital solutions essential to national development.

Morocco has undertaken several initiatives to build out those institutional frameworks, including the establishment of a dedicated Ministry of Digital Transition and a draft law creating a National Agency for AI Governance.

The most ambitious step came this summer, when the country’s central bank launched the e-Dirham, a sovereign digital currency designed to modernize payment systems and reduce cash usage. The system operates on a private blockchain, and all transaction data is controlled by national authorities.

The launch came as authorities in Rabat move to regulate the country’s rapidly growing crypto economy. Despite a 2017 ban on crypto assets, clandestine transactions continue to grow, mirroring similar dynamics in Algeria and Tunisia. Across the Maghreb, a form of unregulated digital liberalization has emerged, fueling speculative behavior.

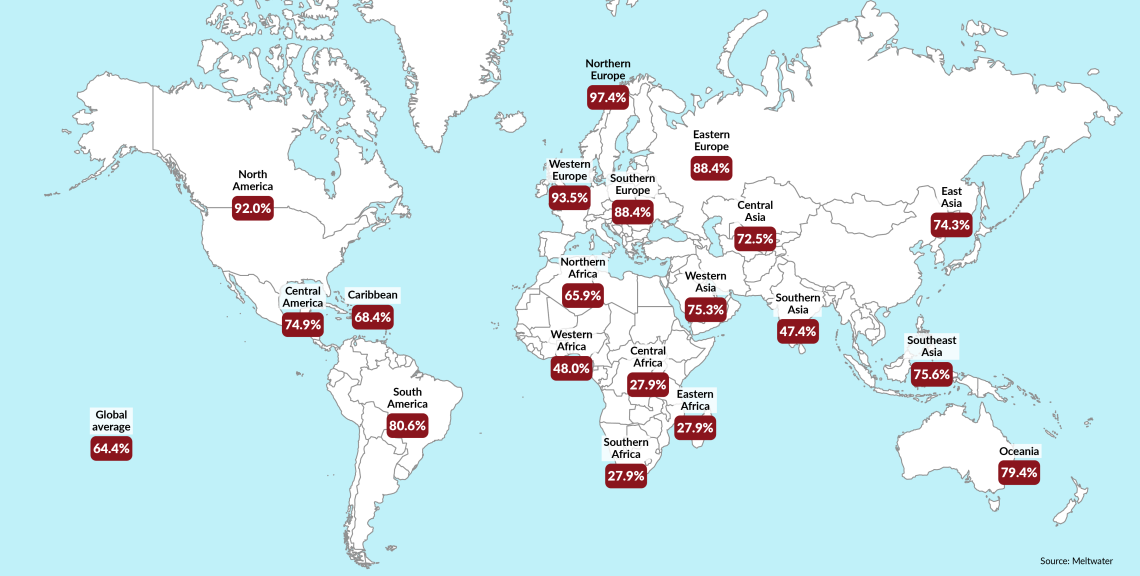

Internet users as a percentage of total population

Unequal internet access across the African continent will make implementation of digital reforms more challenging for governments in the region. © GIS

Unequal internet access across the African continent will make implementation of digital reforms more challenging for governments in the region. © GIS

Morocco is estimated to have nearly 6 million cryptocurrency users. The e-Dirham initiative seeks to reassert state oversight of an expanding informal market and shield citizens from fraudulent schemes.

On the one hand, Morocco wants to modernize its economy, digitize payments and promote tech entrepreneurship. On the other, Rabat governs a population in which 35 to 46 percent remain unbanked, and where rural families are increasingly affected by a new barrier: digital illiteracy. Approximately 40 percent of the rural population are unable to use tools such as smartphones, the internet or mobile applications.

In search of a new business model

One of the biggest technological challenges facing the Arab world is the rise of AI. The region is entering this new era in a fragmented fashion. While developments in North Africa remain limited, Libya has surprised observers by announcing the upcoming launch of LibiGPT, a national AI system presented as a symbol of digital revival. Morocco, anxious not to miss this technological leap, is still searching for its footing.

In the Arabian Peninsula, AI has become a strategic priority backed by massive financial resources. Saudi Arabia, for example, has launched a national readiness index, designed to evaluate how prepared its public institutions are to integrate AI. Across the region, the message is clear: Institutional adoption of artificial intelligence is no longer a matter of debate. The global race is underway, and no country can afford to remain behind.

The digital asymmetry between Arab states reflects profound structural disparities in development. In Morocco, as in most countries across the region, e-commerce contributes less than 1 percent of gross domestic product, while rural populations continue to face unresolved challenges such as access to clean water, healthcare and quality education.

Rabat wants to harness the transformative potential of AI. Yet the reality is that young Moroccan tech entrepreneurs are still under-supported. Moroccan banks remain hesitant to back their ventures, often requiring guarantees that these entrepreneurs simply cannot provide.

More by North Africa expert Pierre Boussel

Underneath this caution lies a persistent belief that traditional economic sectors such as food or consumer goods are safer than intangible, innovation-driven projects. But artificial intelligence is disrupting these long-held assumptions. Relying on imported AI solutions risks creating dependency and ignoring local needs.

Another issue is whether Morocco can build an AI ecosystem that benefits the whole country, not only hubs like Casablanca, Tangier and Marrakesh. AI could potentially drive regional development by tapping talent in the underprivileged interior.

The Jazari Institute, based in the economically disadvantaged Guelmim-Oued Noun region, wants to use artificial intelligence as a driver of development. It focuses on key sectors, like smart farming, digital health, renewable energy and sustainable tourism, as well as ocean and coastal resources.

These initiatives cannot change Morocco’s technological path on their own, but they send an important signal. They show a move from passive observation to active participation in the global digital shift, including in regions that were long left behind. They also reveal the challenges ahead: AI integration will likely be slow, uneven and difficult.

Scenarios

Least likely: Morocco fails to capitalize on the AI revolution

In the absence of a coherent industrial policy, Morocco becomes structurally dependent on imported AI solutions. Its businesses remain confined to a narrow, uncompetitive domestic market. The country turns into a consumer of innovation, lacking both interoperability and influence. This results in a youth searching for alternative income streams, where crypto speculation becomes less a sign of modernity than an admission of failure.

Despite a promising start, Morocco fails to capitalize on its momentum. A small minority benefits from the tech revolution, while the majority is left behind. The lack of opportunities in innovative sectors pushes Moroccan talent to migrate to Europe, Canada or the Gulf states. The few locally trained professionals are quickly recruited abroad through global talent acquisition platforms targeting North Africa.

Most likely: Morocco successfully implements digital reforms

Faced with the urgency of digital transformation, Morocco eventually acknowledges the need for a deep reform of its development model. This awareness emerges gradually, driven by a combination of public initiatives and warning signals from the ground: declining competitiveness, brain drain and growing technological dependence.

Training programs in data science and AI engineering expand across several regions; innovation incentives are introduced to support local start-ups; and public administrations begin their digital transition. In parallel, the state seeks to establish coherent digital and AI governance, capable of aligning local and national efforts.

The country also uses its geostrategic position to attract high-value-added tech projects. The population, initially cautious, progressively engages in this effort. Access to digital education, the widespread use of mobile tools and economic pressures lead many young people to acquire technological skills.

Contact us today for tailored geopolitical insights and industry-specific advisory services.