In the early hours of June 22, at the height of the 12-day war between Israel and Iran, the U.S. joined the conflict and dropped 14 30,000-pound bunker-buster bombs targeting Iranian nuclear facilities in Natanz, Fordow, and Isfahan.

In the days that followed, the Trump administration went after Iranian targets of a very different kind: immigrants living in the U.S., the majority of whom had no convictions or pending criminal charges, a Prism investigation has found. The disproportionate surge in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrests of hundreds of Iranians, including international students and permanent residents, continued even after Iran and Israel agreed to a ceasefire.

The findings are even more significant amid a rare agreement between the Islamic Republic of Iran and the U.S. government announced on Sept. 30. As part of the deal, Iran agreed to take in 400 of its nationals whom the Trump administration has sought to deport. On Sept. 29, a U.S. government-chartered flight carrying 120 of these deportees took off from Louisiana and arrived in Tehran. Several of the Iranians targeted by ICE and facing threats of deportation are dissidents or critics of the Islamic Republic, making them especially vulnerable to such an agreement.

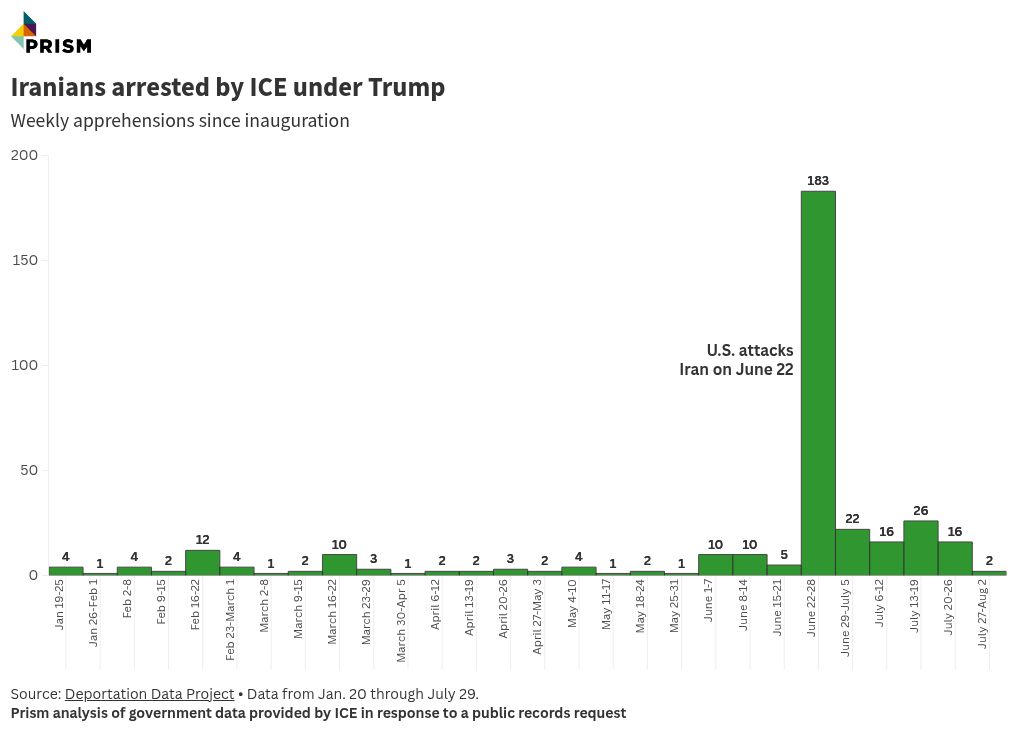

ICE apprehended 351 Iranian citizens from the start of the current Trump administration on Jan. 20 up until July 29, according to the latest official government data provided by the immigration enforcement agency in response to a public records request by the Deportation Data Project. More than half of the arrests, or 183, came in the week following June 22, the day the U.S. bombed Iran during the 12-day war between Israel and Iran, according to Prism’s analysis of the data.

As many as 109 of those arrested, representing 60% of Iranians apprehended that week, were neither convicted of a crime nor had pending criminal charges. The weeklong enforcement overdrive saw Iranian immigrants arrested in 14 states, with the highest number of apprehensions taking place in California and New York, followed by Texas and Florida.

The developments have alarmed advocates, lawyers, and immigration experts, several of whom told Prism that the findings reflect a pattern of the Trump administration deliberately and unfairly targeting individuals of a specific community.

Etan Mabourakh, an organizing director with the National Iranian American Council, told Prism that the Iranian community in the U.S. is experiencing “an urgent crisis of heightened and racially motivated targeting for deportation.”

“These arrests were driven by nationality, not evidence,” Mabourakh said. “Immigration enforcement is absolutely being misused as a political tool and is an example of how war abroad heightens repression at home.”

These arrests were driven by nationality, not evidence. Immigration enforcement is absolutely being misused as a political tool and is an example of how war abroad heightens repression at home.

Etan Mabourakh, National Iranian American Council organizing director

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and ICE did not respond to Prism’s requests for comment. In a post on X on Sept. 25, reacting to media reports about its operations in Washington, D.C., DHS refuted allegations of racial profiling.

“What makes someone a target for immigration enforcement is if they are illegally in the U.S.—NOT their skin color, race, or ethnicity,” the post reads.

However, on June 24, the day a ceasefire came into effect between Israel and Iran, DHS published a press release announcing the detention of 11 Iranian immigrants. The statement was unusual in that it pointed a finger at a specific nationality and grouped arrests across different states—their only connection being that the individuals were all Iranian.

A relative of one of the Iranians arrested, who did not want to be named due to safety concerns, told Prism that an immigration enforcement agent remarked after the arrest that they had been instructed to go after Iranian immigrants following the Israel-Iran war.

Vulnerable dissidents

The majority of Iranians in the U.S. are critical of the Iranian government, and a large number of them had left Iran as dissidents. For many of them, the looming fear of deportation places them in a precarious situation. For instance, Mabourakh said one of the people detained by ICE was an Iranian immigrant who had sustained injuries during the anti-government “Woman, Life, Freedom” protests in Iran in 2022.

Many of the detainees also belong to vulnerable minority groups who have faced persecution in Iran. A Baha’i father arrested by ICE in Phoenix, a Christian convert apprehended in Colorado Springs, and a Christian asylum-seeker detained in Los Angeles are some examples of the Iranians whose religious beliefs left them especially at risk in the event of deportation. Members of religious minority groups or political dissidents deported in the past have faced retaliation in Iran.

Historically, the government of Iran has not cooperated with U.S. immigration authorities in accepting its deported citizens, and this was cited as one of the reasons in President Donald Trump’s proclamation for instituting a travel ban on Iran in June. This dynamic appears to be changing with the unprecedented Tehran-Washington agreement on deportations, which took effect at the end of September.

The Trump administration has also shown a proclivity to deport immigrants to countries they are not from. That’s concerning to Parastoo Zahedi, an Iranian-American immigration attorney based in Virginia who is representing an Iranian ICE detainee. A judge has ruled that her client should not be deported to Iran.

“If he’s deported to a third country as designated for my client, which is Pakistan or Turkey or Qatar, those countries have policies and relations in place with Iran—they’re going to refoul him straight back to Iran,” she told Prism.

The Iranians who have been swept up in the ongoing crackdown include some who have described themselves as supporters of Trump’s MAGA movement, and even those who had been proponents of heightened immigration restrictions.

Arpineh Masihi, a 39-year-old mother of four who has lived in the U.S. since she was 3 and is in removal proceedings, told the BBC from the Adelanto ICE Processing Center north of LA that she is confident that “good people” will be released and only “the ones that are bad” will be sent back.

“I will support him until the day I die. He’s making America great again,” she said of Trump. Masihi, a Christian, doesn’t have the option of going back to Iran due to fears she could face persecution as a member of a religious minority.

Even before the Israel-Iran war, the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement authorities had acted against certain Iranians on questionable grounds.

Alireza Doroudi, a former doctoral student at the University of Alabama, was arrested by ICE in March after being charged with posing a national security threat. At a final court hearing, DHS said it was ready to drop the charges because of a lack of evidence. But Doroudi, drained by 68 days of detention, chose to leave the U.S. and return to Iran on June 1.

In August, the State Department’s Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs issued a strong warning to Iranian Americans, discouraging them from traveling to Iran due to a high risk of “wrongful detention.” However, the same administration has sought to deport Iranian immigrants, including to their home country.

Fear in the community

Mahsa Khanbabai, a prominent immigration attorney and an elected director of the board of governors of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, told Prism that the impact of Iranians being targeted was being felt in the community far beyond those who have been arrested.

“I think the government is basically achieving their goal, spreading chaos and fear in the community,” Khanbabai said. “Grab a hundred Iranians, and it’s going to cause a ripple effect. People will leave on their own, they won’t apply for visas, they won’t try to come here.”

Zahedi said she has seen Iranian immigrants choose to leave on their own amid the climate of intimidation.

“One of my own clients said, ‘I don’t want to get up every day and worry if I walk out that I’m going to be kidnapped. I don’t want that worry; I escaped from Iran to escape from being arrested at any time.’ He’s in Turkey now,” Zahedi said. “A lot of people are just leaving. They’re just done with it.”

The impact is worsened by the travel ban on Iranians entering the U.S. or applying for new visas. In the previous iteration of the so-called Muslim ban that went into effect in 2017 during Trump’s first presidency, Iranian students were exempt from the restrictions as they were believed to be beneficial to U.S. education. This time around, that exemption has not been offered.

“Alas, a wholesale travel ban disproportionately hurts Iranians who are not fond of their own government and deprives America of the talent that smart students and entrepreneurial migrants can contribute,” Mehrzad Boroujerdi, an Iranian American academic and dean of the College of Arts, Sciences, and Education at Missouri University of Science and Technology, said in a text message.

Despite his current policy, Trump has acknowledged the contributions of Iranian immigrants on several occasions in the past.

“For many years, I have greatly enjoyed wonderful friendships with Iranian Americans, one of the most successful immigrant groups in our country’s contemporary history,” Trump wrote in his message on the eve of the Persian New Year in 2017. The drastic surge in arrests of Iranian immigrants in recent months points to a new political reality.

Mabourakh of the National Iranian American Council said the hostilities abroad had resulted in an erosion of civil liberties at home for Iranians living in the United States. “This is about punishing an entire community for theater rather than addressing genuine security concerns,” he said.

Related