Ana Esther Ceceña is a Mexican economist and geopolitical analyst known for her expertise in Latin American affairs. She serves as the director of the Latin American Observatory of Geopolitics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). Her scholarly work explores the dynamics of power, sovereignty, and resistance, with a focus on strategic resources and the global capitalist system.

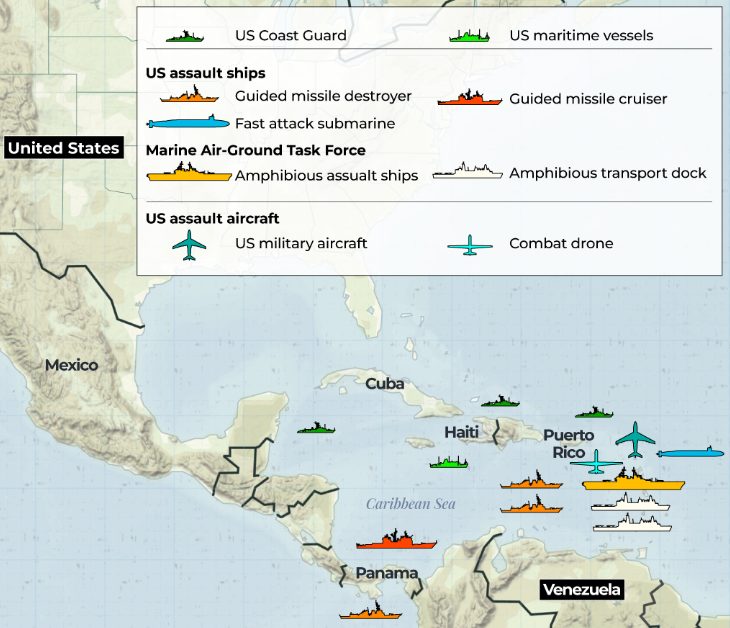

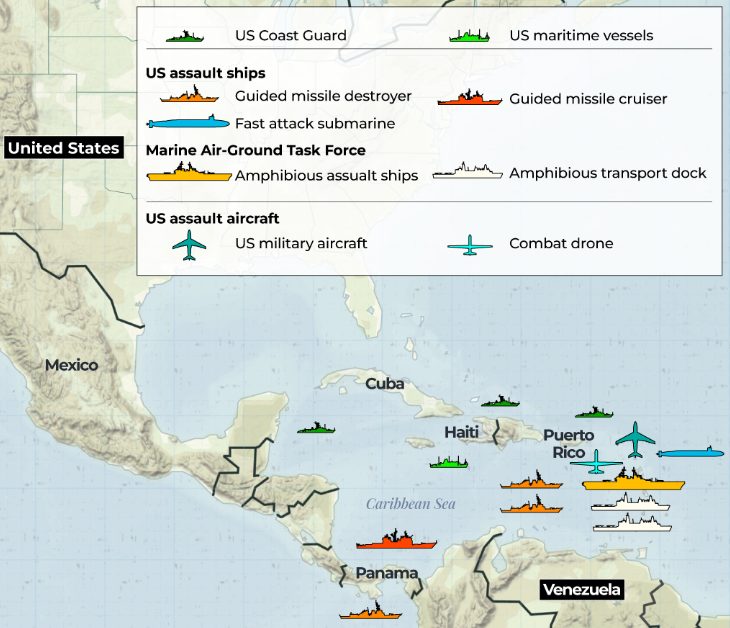

In this interview, carried out in Caracas during the recent “Colonialism, Neocolonialism, and the Territorial Dispossession by Western Imperialism” (October 2-4), Ceceña offers an incisive analysis of Venezuela’s role in contemporary global geopolitics. She discusses the implications of the recent US military escalation in the Caribbean, the strategic significance of Venezuela’s resources, and the broader geopolitical conflicts involving major global powers. Ceceña also reflects on the resilience of the Venezuelan people and their struggle for sovereignty amidst external pressures.

A Pentagon leak published recently by Politico suggests that Washington could be pivoting away from China toward “protecting the homeland and the Western Hemisphere,” effectively reviving the old Monroe Doctrine under new terms. How do you read this apparent strategic turn?

The United States has long identified four countries—Russia, China, North Korea, and Iran—and a non-state entity—Al-Qaeda and its derivatives—as its main enemies. These remain the strategic adversaries for the US.

The US has been following this program closely, primarily confronting China but also engaging via proxy conflicts with the others: a war against Iran through Israel (which recently escalated to direct attack) and a war against Russia through Ukraine.

However, to confront these strategic enemies, Washington needs to control the American continent. That is why we now see the hemisphere becoming its main priority. Latin America, with its natural resources and geographic advantages, including its relative insularity, has always been central to US military strategy. However, a period of intensification is opening up. Their idea is that as long as the US controls the Americas, it effectively cannot be attacked on its territory. It’s as if the US were surrounded by a moat.

However, the correlation of forces in the continent has been changing: China, Russia, and even Iran—three of their five so-called enemies—are already in the region. China is making large-scale commercial agreements and infrastructure investments with most countries in the hemisphere, building ports and establishing trade routes. China is already here, competing in the US’s own “backyard.”

Meanwhile, Russia provides military support to Venezuela and maintains a strong presence in Cuba. This is a huge problem for the United States, particularly because Russia now has more advanced military technology than the US in many respects. Its missile production is faster, cheaper, and more efficient, while the US military industry is lagging behind.

The presence of these powers in the Americas weighs heavily on Washington.

Another key reason for the US focus on the continent is economic: without the oil, minerals, and even the labor force of Latin America, it simply cannot sustain itself. It needs territorial footholds and access to extract the region’s resources for its own reproduction.

Alongside the intensified imperialist military buildup against Venezuela, the United States has just issued a license allowing Trinidad and Tobago to exploit offshore gas in Venezuelan boundary waters, while Exxon’s illegal drilling in disputed Essequibo waters continues unabated. How do these moves fit into the broader campaign of resource plunder and military pressure against Venezuela?

It’s not entirely clear what the White House is planning, but it appears to be preparing for multiple scenarios. Positioning military assets around Venezuela is strategic for controlling international transport routes: from there, US forces could intercept vessels and effectively impose a total blockade both inward and outward, cutting off the country’s ability to export its resources. Such a move would have devastating consequences for Venezuela’s economy.

In the Essequibo case, the US is already deeply involved through ExxonMobil, which continues extracting oil despite the ongoing territorial dispute. Washington will not give up that foothold. Even as litigation drags on, Exxon is pumping and storing as much as possible. At the same time, the US may seek to undermine Venezuela’s own production capacity, potentially by targeting refineries or other strategic facilities.

It’s still not clear how this strategy intersects with Chevron’s operations in Venezuela. However, as one of the United States’ flagship oil corporations, Chevron’s continued presence serves US strategic interests and even supports supply chains linked to the Essequibo extraction. Yet any escalation or attack on Venezuela’s oil infrastructure could jeopardize those same arrangements, exposing contradictions within the US approach.

As for the natural gas exploitation along the maritime border between Trinidad and Venezuela, we’ll have to see how the situation develops. The entire regional oil landscape is extremely tense: frictions are mounting with Brazil, and Mexico is also facing intense pressure from Washington.

Mexico extracts oil but lacks the capacity to refine it, so most of its crude ends up in the United States, both through legal channels and via an extensive black market. In fact, a major scandal has erupted over the illegal siphoning of oil from pipelines, which we call “huachicol” in Mexico. Along transport routes, criminal networks tap into ducts to extract crude that is later sold, often across the border. The scale of this illegal trade now surpasses that of legal flows, revealing a highly organized operation with clear counterparts on the US side.

Going back to Venezuela, however, I want to highlight that it represents a problem for the US that surpasses oil: Venezuela is a sovereign country with a transformative project and a combative people. That’s of huge concern to the US.

A young woman who voluntarily enrolled in the militia receives military training. (Nicole Kolster / BBC News Mundo)

A young woman who voluntarily enrolled in the militia receives military training. (Nicole Kolster / BBC News Mundo)

That was precisely my next question. The imperialist aggression is often reduced to Venezuela’s vast oil reserves, but in reality, what’s at stake goes far beyond natural resources. There’s also a political project that poses a challenge to US hegemony. Could you tell us about that?

Venezuela’s resources go far beyond oil. It has gold, access to the Amazon basin, and strategic proximity to the Panama Canal. However, Venezuela’s most extraordinary resource is the consciousness of its people.

Venezuela remains a profoundly Chavista country, marked by geopolitical consciousness and a collective commitment to defending its sovereignty. The role of the military here differs fundamentally from that in countries like Mexico: it is not an invasive force but a people’s army. Many have joined the armed forces as a conscious act of popular defense of national sovereignty. This unity between the people and the military is integral to a broader social and political project that continues to forge its own alternative path.

The experience of the communes, for example, is crucial. There’s nothing like this level of authentic popular democracy anywhere else. Venezuela poses a huge challenge to the United States because it’s not only resilient but also inspiring and it could be contagious.

Venezuela is not isolated. Across the world, new anti-colonial movements such as those in the Sahel are rising. There, people once considered powerless are now standing up. If they can, why not others? Venezuela is part of this broader tide of popular emancipation. At the same time, international initiatives like BRICS are charting new forms of cooperation among nations that challenge the existing global order.

Would you agree with those who argue that US imperialism is facing a crisis of hegemony?

Absolutely! The US is in serious trouble. The loss of terrain in economic terms is most obvious: they aren’t able to bring manufacturing back, and the US dollar is no longer the exclusive global currency. In short, if the United States is acting somewhat erratically, that’s because it is struggling to maintain global political and military dominance.

Is the US also losing ground militarily?

Yes, significantly. As I mentioned before, Russian military technology is now superior in many respects, and China, North Korea, and Iran have also developed powerful capabilities. Each excels in different areas, and together they form a formidable bloc. Also, their armies are much larger than the US. China’s recent military parade revealed a massive, technologically advanced force.

The Bolivarian Government, which broke diplomatic relations with Israel in 2009, has been steadfast in its solidarity with the people of Palestine, and it has not hesitated in calling the genocide by its name. How do you situate the genocide in Gaza within this global geopolitical context?

There’s a global competition underway for control of key trade routes for oil, resources, and goods. A central factor to explain what is going on in Palestine is the US proposal for a commercial corridor linking India to the Mediterranean via West Asia, designed to counter China’s Belt and Road Initiative. This corridor would pass through Israel and necessarily across Gaza, making Gaza strategically important as a potential alternative to the Suez Canal.

Additionally, Gaza’s coastal waters contain significant gas deposits discovered relatively recently. Since then, Israel has sought to reduce Gaza’s maritime boundaries, while British companies, backed by the UK government, have moved in to exploit these resources. That’s one reason for Britain’s complicity in the ongoing conflict.

Palestinians are struggling against a colonialist project, but they are also dealing with direct imperialist interests: natural resources and strategic geography. And once more, we see the same actors: the big corporations and the main powers of the “collective West,” namely the US, Britain, and occasionally France or Germany. Israel serves as the regional platform for their operations, doing the dirty work of territorial cleansing.

Another largely ignored case is Sudan, on the Red Sea. It’s also being torn apart by war and mass displacement. Sudan’s location is crucial geopolitically and for trade routes and, like Venezuela, it’s rich in oil.

When you look at an oil reserves map, you can see a clear belt stretching from Central Asia to West Asia through Africa and reaching Venezuela… and where are most conflicts unfolding? Along that corridor. Venezuela sits at the western end of this chain.

Going back to Venezuela, how far do you think US imperialism’s current military escalation will proceed?

It’s difficult to say. Washington is now threatening not only air and naval operations but also potential ground incursions. A direct invasion, however, would entail full-scale war, which US forces are unlikely to undertake. More feasible are surgical operations such as attacks on oil facilities or key infrastructure.

They have already attempted regime-change operations similar to the Noriega-style “extraction” of Maduro, but these efforts failed. Venezuela’s high level of organization makes such actions extremely difficult. That said, they are likely to continue attempting smaller-scale incursions along the coast.

The situation isn’t easy for Venezuela, as it cannot rely fully on support from the continent, which is fragmented. Nevertheless, the country retains allies and, most importantly, it has the strength of its people, who are organized, actively participate in the militia, and are prepared to defend the nation.

US military deployment near Venezuela. (Aljazeera)

US military deployment near Venezuela. (Aljazeera)