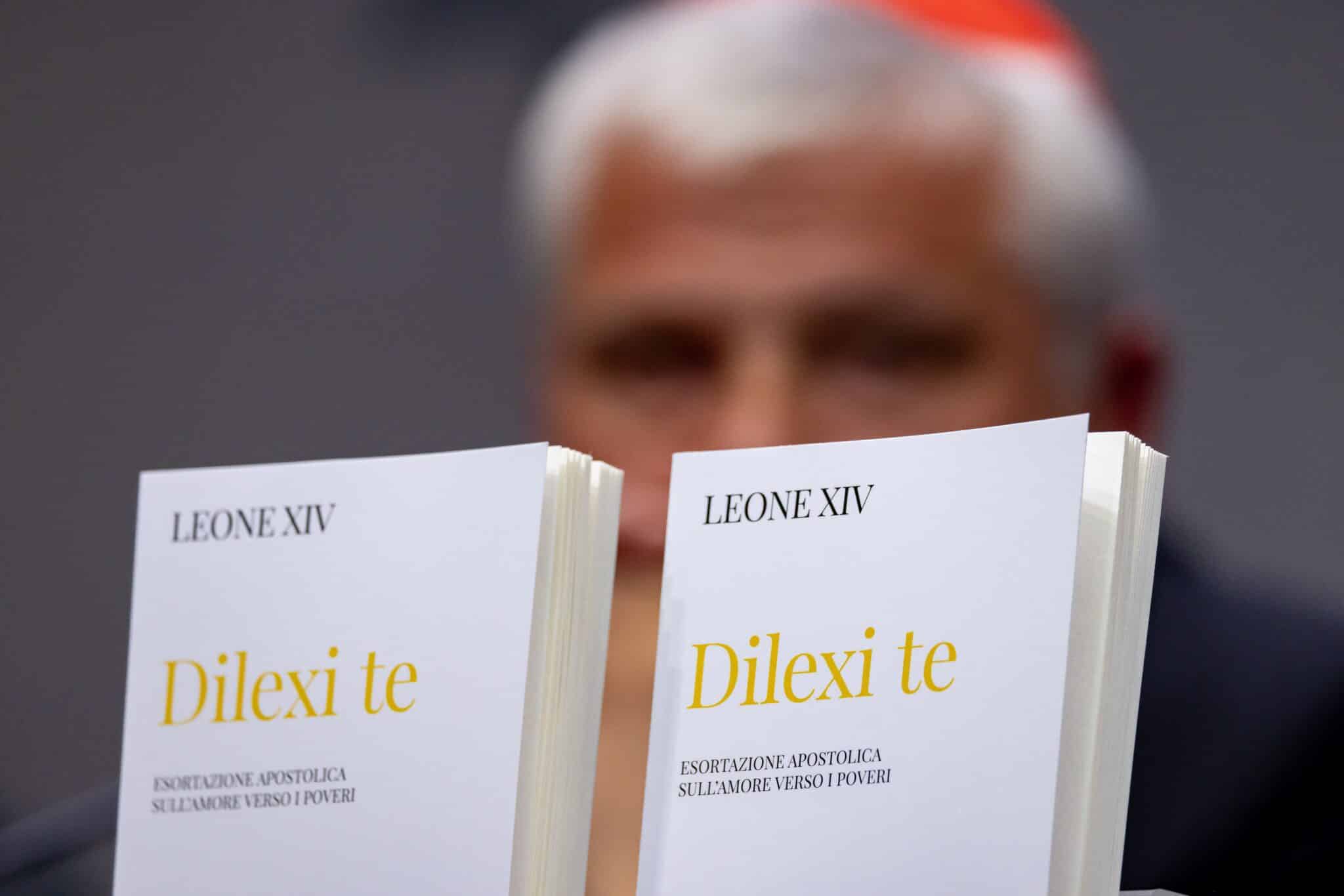

Copies of the Italian translation of “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), Pope Leo XIV’s apostolic exhortation, are seen in front of Cardinal Konrad Krajewski, prefect of the Dicastery for the Service of Charity, at a Vatican news conference Oct. 9, 2025. (CNS photo/Pablo Esparza)

Copies of the Italian translation of “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), Pope Leo XIV’s apostolic exhortation, are seen in front of Cardinal Konrad Krajewski, prefect of the Dicastery for the Service of Charity, at a Vatican news conference Oct. 9, 2025. (CNS photo/Pablo Esparza)

Leo XIV’s debut papal document about love for the poor, Dilexi te (I have loved you), is a collaboration with his predecessor.

When he died, Pope Francis was drafting a companion document to the encyclical he published last October, Dilexit nos (he has loved us), on “the human and divine love of the Heart of Jesus Christ.” Dilexi te is much shorter but is similar in structure and tone.

This is not the first time that a new pope has made his own an unfinished text from his predecessor. Francis’s first encyclical, Lumen Fidei, reworked a text prepared by Benedict XVI. Francis is cited numerous times in key passages, confirming how closely aligned the two popes are.

“I am happy to make this document my own – adding some reflections – and to issue it at the beginning of my own pontificate, since I share the desire of my beloved predecessor that all Christians come to appreciate the close connection between Christ’s love and his summons to care for the poor,” Leo writes. “I too consider it essential to insist on this path to holiness, for ‘in this call to recognise him in the poor and the suffering, we see revealed the very heart of Christ, his deepest feelings and choices, which every saint seeks to imitate.’” [

It’s hardly surprising that a pope should insist on care for the poor – 2000 years of Catholic tradition confirm this, as Dilexi te documents.

What is surprising is the prominence and passion that Leo brings to this theme. He may be the first American pope, but he is also the first Peruvian pope, and he has first-hand knowledge of the wretched of the earth.

After a Vatican news conference to present Pope Leo XIV’s apostolic exhortation “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), Oct. 9, 2025, the speakers pose for a photo. From the left they are: Father Frédéric-Marie Le Méhauté, provincial of the Franciscan friars in France and Belgium; Cardinal Konrad Krajewski, prefect of the Dicastery for the Service of Charity; Cardinal Michael Czerny, prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development; and Sister Clémence, a member of the Little Sisters of Jesus. (CNS photo/Pablo Esparza)

After a Vatican news conference to present Pope Leo XIV’s apostolic exhortation “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), Oct. 9, 2025, the speakers pose for a photo. From the left they are: Father Frédéric-Marie Le Méhauté, provincial of the Franciscan friars in France and Belgium; Cardinal Konrad Krajewski, prefect of the Dicastery for the Service of Charity; Cardinal Michael Czerny, prefect of the Dicastery for Promoting Integral Human Development; and Sister Clémence, a member of the Little Sisters of Jesus. (CNS photo/Pablo Esparza)

The document, an apostolic exhortation, one rung down from an encyclical in terms of its authority, is not difficult to follow. It will only take a persevering reader about an hour and a half to complete. It’s best to read it for yourself, but here are five takeaways if you’re short on time.

Leo renews the church’s commitment to a “preferential option to the poor”

In a striking turn of phrase, Leo says “when the church bends down to care for the poor, she assumes her highest posture.” A “preferential option for the poor” does not exclude other groups. It stems from the fact that the Redeemer of mankind was born in poverty and lived in poverty.

Perhaps anticipating criticism from conservatives who might detect a “left-wing” bias, Leo doubles down. “A preferential option on the part of God for the poor [is] an expression that arose in the context of the Latin American continent and in particular in the Puebla Assembly, but which has been well integrated into subsequent teachings of the church.”

“Wanting to inaugurate a kingdom of justice, fraternity and solidarity, God has a special place in his heart for those who are discriminated against and oppressed, and he asks us, his church, to make a decisive and radical choice in favour of the weakest,” Leo writes.

People living in poverty are subjects, not objects

One of the most striking affirmations of Dilexi te is that the poor can teach the rich.

“All of us must let ourselves be evangelised by the poor,” Leo writes, citing Pope Francis’s first major document, Evangelii Gaudium.

A journalist looks through the Italian translation of “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), Pope Leo XIV’s apostolic exhortation, during a news conference at the Vatican to present the document Oct. 9, 2025. (CNS photo/Pablo Esparza)

A journalist looks through the Italian translation of “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), Pope Leo XIV’s apostolic exhortation, during a news conference at the Vatican to present the document Oct. 9, 2025. (CNS photo/Pablo Esparza)

“Those of us who have not had similar experiences of living this way certainly have much to gain from the source of wisdom that is the experience of the poor. Only by relating our complaints to their sufferings and privations can we experience a reproof that can challenge us to simplify our lives.”

Concern for the poor is a perennial theme of the great teachers

“How I would like a church which is poor and for the poor!” Pope Francis remarked at the beginning of his pontificate. Leo is of the same mind. In a long chapter of Dilexi te, he underscores how passionate the early Fathers of the Church were about caring for the poor.

He cites St Paul the Apostle, St Justin Martyr, St Lawrence, St Ambrose, St Ignatius of Antioch, St Polycarp, and naturally St Augustine, for whom “the poor are not just people to be helped, but the sacramental presence of the Lord.”

But the “most ardent” advocate of the poor, Leo recalls, was St John Chrysostom, the Archbishop of Constantinople in the late 300s to the early 400s. He spoke with a ferocious vigour: “Do you wish to honour the body of Christ? Do not allow it to be despised in its members, that is, in the poor, who have no clothes to cover themselves. Do not honour Christ’s body here in church with silk fabrics, while outside you neglect it when it suffers from cold and nakedness…”

Closer to our own times, since Leo XIII the popes have been prophetic voices urging Catholics to have a social conscience. “The Church’s Magisterium in the past 150 years is a veritable treasury of significant teachings concerning the poor,” he reminds readers.

A journalist takes notes during a Vatican news conference to present “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), Pope Leo XIV’s apostolic exhortation, Oct. 9, 2025. (CNS photo/Pablo Esparza)

A journalist takes notes during a Vatican news conference to present “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), Pope Leo XIV’s apostolic exhortation, Oct. 9, 2025. (CNS photo/Pablo Esparza)

The church pioneered modern welfare institutions

The historical amnesia which afflicts our universities and media means that most people are ignorant of the foundations of modern welfare institutions. It started early. The first Christians survived the plagues which swept through the Roman Empire because they cared tenderly for each other, as St Cyprian of Carthage testified.

Modern hospitals and nursing care were not invented by Florence Nightingale in the 19th century. Great figures like St John of God and St Camillus de Lellis developed hospitals. “The Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, the Hospital Sisters, the Little Sisters of Divine Providence, and many other women’s congregations have become a maternal and discreet presence in hospitals, nursing homes and retirement homes,” Leo reminds us.

And long before governments became responsible for educating children, great Catholic figures were founding schools – St Joseph Calasanz in Rome in the 16th century, the Ursuline sisters, St Marcellin Champagnat in France in the 19th century – and many more. “Each child was considered a unique gift from God, and the act of teaching was a service to the Kingdom of God,” Leo observes about St John Baptist de La Salle, who worked in France in the 17th century.

The invisible hand of the market will not solve poverty.

The first American pope is not a fan of laissez-faire capitalism. In his first sit-down interview he commented on entrepreneur Elon Musk’s compensation package. “Yesterday [there was] the news that Elon Musk is going to be the first trillionaire in the world,” he said. “What does that mean and what’s that about? If that is the only thing that has value anymore, then we’re in big trouble.”

Pope Leo XIV signs his first apostolic exhortation, “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), in the library of the Apostolic Palace at the Vatican Oct. 4, 2025, the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, as Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra, the substitute secretary for general affairs at the Vatican Secretariat of State, looks on. The exhortation will be released Oct. 9. (OSV News photo/Vatican Media/CPP)

Pope Leo XIV signs his first apostolic exhortation, “Dilexi Te” (“I Have Loved You”), in the library of the Apostolic Palace at the Vatican Oct. 4, 2025, the feast of St. Francis of Assisi, as Archbishop Edgar Peña Parra, the substitute secretary for general affairs at the Vatican Secretariat of State, looks on. The exhortation will be released Oct. 9. (OSV News photo/Vatican Media/CPP)

In a section of Dilexi te headed “Ideological prejudices” he writes “The poor are not there by chance or by blind and cruel fate. Nor, for most of them, is poverty a choice. Yet, there are those who still presume to make this claim, thus revealing their own blindness and cruelty.”

The church must be “committed to resolving the structural causes of poverty.” The current standard for progress, which privileges success and self-reliance, is inadequate.

Leo writes passionately: “Does this mean that the less gifted are not human beings? Or that the weak do not have the same dignity as ourselves? Are those born with fewer opportunities of lesser value as human beings? Should they limit themselves merely to surviving? The worth of our societies, and our own future, depends on the answers we give to these questions. Either we regain our moral and spiritual dignity or we fall into a cesspool.”