Strolling past the golden domes of St Michael’s monastery on a September Saturday evening, the casually dressed, bearded and bespectacled character in his mid-30s blends effortlessly into the Kyiv crowd.

But Taras Semeniuk is no ordinary weekend visitor, even by wartime standards, when many thousands of Ukrainian citizens have volunteered to defend their country against Russian attacks.

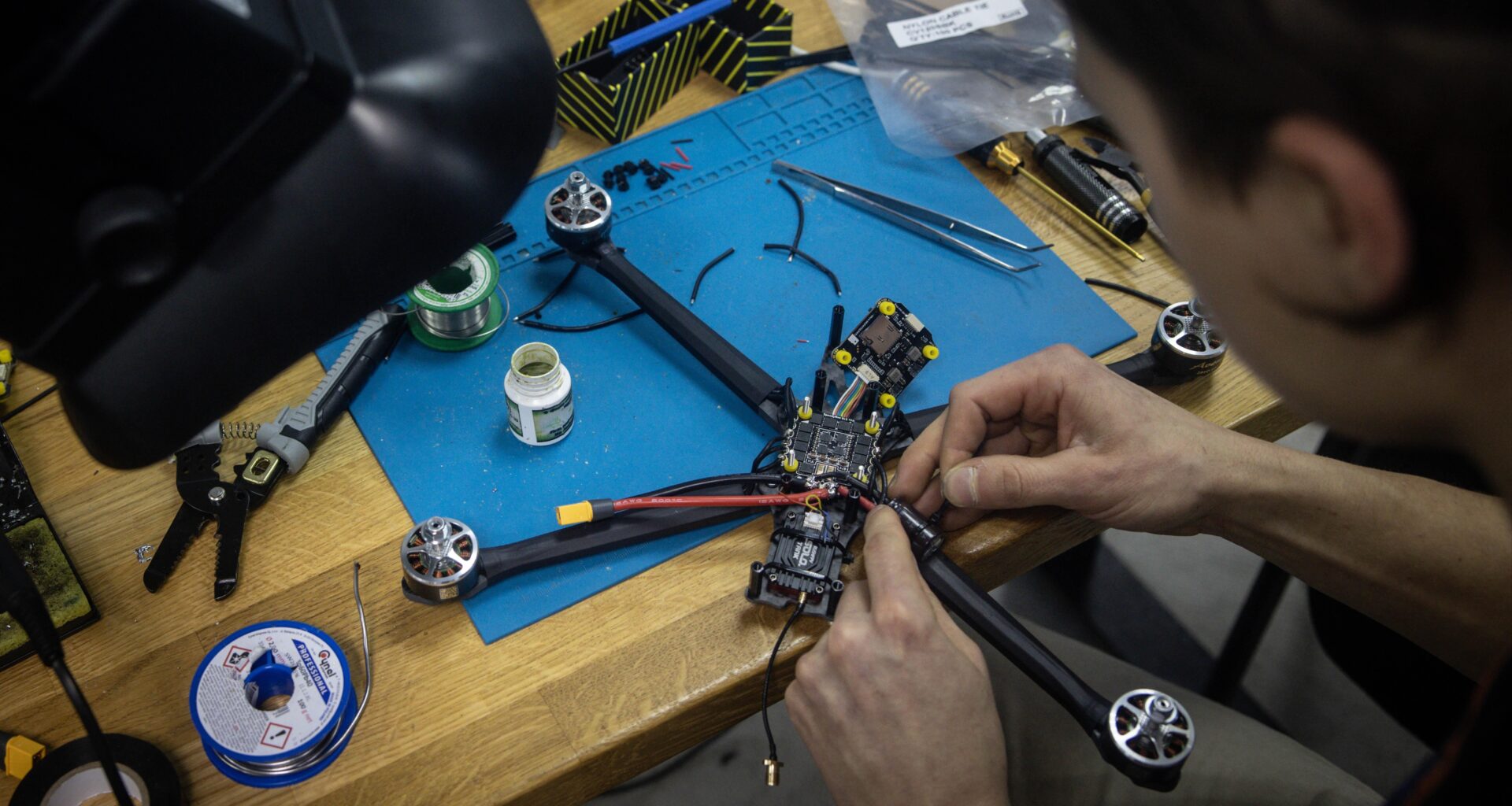

The dentist turned drone designer, fresh from flying his latest prototypes on the city’s outskirts, is embarking on a regional tour, to meet like-minded technicians, assemblers and investors.

From 2017, Mr Semeniuk was moulding clear plastic mouthguards to re-align crooked teeth and by 2021 had opened private clinics, treating more than 800 patients across the Ukrainian cities of Lviv, Kyiv, Khmelnitsky and Dnipro. His “huge laboratory” was stacked with 3D printers and scanning machines.

Central Europe Stirring Special Report

Many geopolitical commentators expect a peace deal to be signed to end the Ukraine war in 2025, leading to a $1tn infrastructure rebuilding programme and investment opportunities. There are also several countries in the region which have matured from frontier bets to core portfolio positions, including Poland and Romania. Our special report takes a look

After selling his firm to a Spanish investor, but remaining as CEO, he oversaw the launch of new clinics in the UK, France, Germany and US, emphasising a business switch to treating a mass market of clients outside Ukraine.

But once the Russian army invaded in February 2022, Mr Semeniuk became concerned about a different patient — the Ukrainian nation, and how to protect it against Russia’s aerial and ground attacks.

Starting with designing remote-controlled jeeps, he hit on the idea of using tethered drones suspended on a high antenna, in place of more expensive and technically complex GPS systems.

Using his collection of Hewlett Packard 3D printers, Mr Semeniuk, and his team at Huless, began duplicating the drones soon after the invasion, creating an industrial manufacturing process. Their 30km range soon attracted contract purchases from the Ukrainian army, following initial investments from friends and family. Now he has started looking for foreign funds, particularly from the UK and Switzerland.

“We understand that our investments from Ukraine can help us build high level technologies,” says Mr Semeniuk. “But to make things move faster, we need much more.”

Combination nation

The main skill of Ukrainians, he believes, is not developing new technology, but combining existing technologies to create innovative products.

“FPV drones are not high-quality, high-tech devices,” he admits, describing the incorporation of his remote-controlled ariel vehicles into “Ukraine’s doctrine of usage” of military technologies.

“But when we produce four million of them, teach our soldiers how to use them and make them more efficient with AI, then you can see why we have become so interesting for investors in the UK and other countries. They can see that we know how to use these technologies.”

While test-flying his drones around Kyiv and locations in western and eastern Ukraine, he often phones his team of engineers to make modifications, which are ready within days.

“This shows our investors it’s not just about manufacturing the drones, but how we improve them after manufacture that makes the difference,” reveals Mr Semeniuk.

When speaking with entrepreneurial families and other investors about his projects, he prefers to deal with those already familiar with investing in defence and military technology. “The best investor is always a company from within the industry, because they will understand what we do, and we like to be partners with these people,” he says.

Western investors are typically interested in the “dual-use” aspect of Ukrainian technology — applicable to both peace and wartime. But for many of Ukraine’s military tech developers, it is battlefield use which is currently most pertinent.

“The philosophy of our company is to save lives, not end them,” says Yaroslav Filimonov, CEO of Kvertus, a Ukrainian developer and manufacturer of anti-drone systems for military use. Mr Filimonov was on a business trip to Dubai when Russia attacked Kyiv in February 2022 but quickly returned to help defend critical infrastructure.

Living off the wall

Together with the firm’s founder, Andrii Znaichenko, he launched the Atlas project, creating an advanced anti-drone “wall” to span the frontline, using electronic warfare technologies “to protect soldiers, civilians and critical infrastructure from the escalating threat of Russia’s unmanned aerial vehicles”.

So far they have received $16m in funding from Ukrainian Olympic fencing champion Olga Kharlan, Ukrainian bank PUMB, private hospital chain Dobrobut and agricultural firm MHP. They are seeking $135m in total investments.

“Everything is dual use these days,” says Mr Filimonov, a military psychologist by training. “Before the war, drones were about entertainment, filming landscapes, weddings and birthday parties,” he recalls. “But from 2022, they became a weapon which started to kill people. I came back to Ukraine because it’s my homeland. Me and my team earned some money, and then in 2023, we started to re-invest in defence technology.”

Ukrainian Olympic fencing champion Olga Kharlan has provided funding to the Atlas anti-drone project© Getty Images

The Atlas project is able to monitor every enemy drone within Kyiv’s city limits and they plan to expand it to four more Ukrainian cities.

“We’re talking about Star Wars style technology,” says Mr Filimonov, having just returned from one of his three visits each month to the front line in the country’s eastern Donbas region.

“But currently, only 10 per cent of Ukraine’s electronic warfare needs are covered by our government. Imagine that — just 10 per cent of your soldiers are wearing helmets.”

When marketing the Kvertus franchise to funds, Mr Filimonov likes to quote the success metrics associated with his technologies. “We have calculated that we have saved more than 100,000 lives so far, and we can save more,” he says, planning to adapt the technology to provide security for industrial premises, airports and sports stadiums after the end of the conflict.

High tech renaissance

Andriy Kolodyuk, founder of Aventures Capital and chairman of the Ukrainian Venture Capital and Private Equity Association, likens today’s technological renaissance in Ukraine to the rise of Silicon Valley in the US from the turn of the Century.

“I started working in Silicon Valley in 2001, where Californian entrepreneurs were telling me how the valley’s founders had pivoted to adapt their military technologies for civic use,” he recalls, between doing the rounds of family offices and sovereign wealth funds at international investment conferences. “We have been in this cycle since the 1960s and 1970s, when Silicon Valley was established.”

Ukraine is experiencing a similar trend, after “a few decades” of a tough fund-raising environment for Ukrainian innovation.

“Now, out of necessity, Ukrainian entrepreneurs are creating these innovative tools, to protect people and provide food security and energy security,” he says, adding that there are 15,000 dual use entrepreneurs designing drones and other aerial devices in Ukraine.

“This dual use technology is now applicable to the old verticals, from agriculture, to disaster management, to the media and all aspects of our lives.”

AI at next level

The next level of innovation, says Mr Kolodyuk, will deploy AI to predict when wars are about to emerge, how to prevent and manage them. “The majority of defence budgets are deployed to fight the consequences of conflicts, after they break out,” he says. “I am more interested in using AI to invest in intelligence, before the conflict happens.”

Investment from PE and venture capital firms, is “enabling Ukrainian drone manufacturers to expand production and further develop their technologies”, suggests Louise Tumchewics, a visiting fellow at the University of Southern Denmark, specialising in modern warfare and supply chains.

“Combat drones are very much a fast-moving area of technological development, and like all emerging technologies, comes with a certain degree of investment risk. Family offices will want to carefully research individual companies and technologies, and assess their risk tolerance before getting involved.”

It is also important to note, she says, that both Russia and Ukraine rely heavily on China for drones’ component parts and materials, and this dependency creates additional supply chain and geopolitical risks.

The market is ripe re-calibration of environmental social and goverance (ESG) investments, says Ms Tumchewics. During the last 20 years, Europe’s pension and investment funds have been forbidden from investing in defence and defence-related stocks, due to the industry’s social and environmental impact, she says. But this could soon be changing.

“At the time that it was introduced, ESG was a reflection of Europe’s prosperity and security in the post-cold war world, and the relative geopolitical stability of the time,” she says. “However, in 2025, we could say energy, security, and geopolitics are the new ESG, reflecting renewed threats to European security, economic uncertainty and geopolitical volatility.”

In January of this year, recalls Ms Tumchewics, Nato secretary-general Mark Rutte called for a review of European pension and investment fund rules that prohibit investment in defence.

“According to Rutte, ESG rules have inhibited development in defence, putting Europe well behind China and Russia in terms of military readiness,” she believes. “If we see continued Russian hybrid aggression, such as the airspace violations in Poland, Denmark and Estonia last month, there may be increasing willingness by funds to redefine the terms of ESG.”

Garage land

Yet there are voices in Ukraine’s political system that question the viability of an economy driven by innovative tech start-ups for so many years. Critics say Kyiv has failed to build the type of efficient military-industrial complex necessary for a powerful sovereign nation.

“Drone manufactures belong to Ukraine’s garage economy,” says Vadym Karasyov, a former adviser to President Victor Yushchenko, elected after the Orange Revolution of 2004. “These people are earning money, but there is no co-ordination, which the state should be involved in.”

An elite, financed by European funds, is distanced from ordinary citizens and is happy to “pour cold water” over its own entrepreneurs.

“We need a more vibrant defence industry, consisting not just of drones. Who shot down Russian drones in Poland? It was the F35s. You don’t win a war with drones,” says Mr Karasyov.

Outside specialist private equity funds, it may also be difficult to convince leading traditional fund managers to invest in Ukraine’s innovative technologies

“Ukraine, pre-war, was one of the most corrupt countries you could find globally, and if the governance regime changes, then perhaps we would be prepared to look at it,” says Andrew Ness, portfolio manager in the emerging markets equity team at US house Franklin Templeton.

“But I think in a post war scenario, it’s going to be very difficult to assume that it’s not going to be as challenging from that front as it was before the war.”

While many funds and start-ups talk about today’s fashionable theme of dual-use technology, Mr Semeniuk’s beliefs are more fundamental.

“Everything depends on what sort of country Russia will become in one year, 10 years or 20 years,” he says, looking at the long-term view of his business.

“In case of another war, Ukraine needs to be a strong country, as we will remain in a high-risk neighbourhood. For sure, this technology can be scaled for civilian purposes. But I think, that for the next five or 10 years, I will focus on the military.”