Whether framed as coincidence or careful arrangement, October 2025 offered a moment of surprising symbolism in Indonesia-North Korea relations. Pyongyang marked its 80th Workers’ Party anniversary just as Jakarta celebrated the 80th year of its armed forces, and against this setting that Indonesian Foreign Minister Sugiono set out on the first visit to North Korea by an Indonesian top diplomat since over a decade. Whereas official statements spoke only of a friendship nature, the strategic timing and Indonesia’s recent defence buildup, suggest deeper strategic interests and have led to speculation that low-profile security ties might be considered.

Jakarta’s Longstanding but Unassuming Relations with Pyongyang

Indonesia’s links to North Korea run deep from the Cold War era but have historically been political rather than military. Diplomatic relations were established in 1964 as an extension of Indonesia’s non-aligned foreign policy, and in later year, Indonesia’s founding father Sukarno hosted North Korea’s Kim Il-sung in Indonesia. After a brief interruption in the late 1960s, Indonesia under Suharto re-aligned toward the West but never officially cut relations with Pyongyang. Megawati Sukarnoputri, Sukarno’s daughter and later Indonesian president, revived personal channels with the Kim family, meeting Kim Jong-il in 2002 and affirming the symbolism of dynastic respect between Jakarta and Pyongyang.

For decades, The two nations have maintained cordial yet understated relations. North Korea maintains its embassy in Jakarta, and after a COVID shutdown, Indonesia reopened its Pyongyang embassy in July 2025. Prabowo also met Kim Jong Un during the Victory Day Parade hosted by Xi Jinping in Beijing. Despite that, Trade ties remain minimal, with official figures indicating a decline from USD 2.3 million in the first eight months in 2024 to USD 2.1 million in the same period in the year after.

Indonesia, North Korea, and ASEAN Reactions

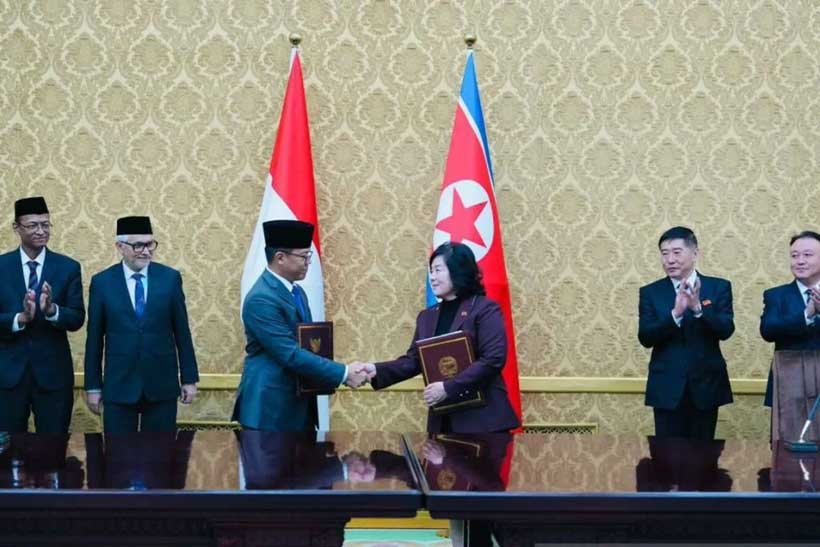

The recent visit saw the two foreign ministers signed a Memorandum of Understanding to establish a formal bilateral consultation mechanism, which would explore cooperation in political, socio-cultural, technical, and even sports sectors. Expectedly, it did not mention military affairs. But any consultation channel, even framed as civilian or political, can carry security implications. And that Indonesia’s renewed engagement with Pyongyang aligns with its enduring commitment to free and active foreign policy doctrine, which maintains balanced involvement with all major powers.

Indonesia, interestingly, has ramped up its defense ambitions since Prabowo took office. The recent Indonesian military anniversary parade displayed new domestically-built and imported systems, specifically the debut of Indonesia’s first autonomous unmanned submarine KSOT-008 that symbolises an intent to close capability gaps in undersea and maritime domains. The country, at its core, has further diversified its arms procurement to include a broader array of partners, acquiring equipment and technology from Turkey, France, Russia, India, the United Kingdom, Italy, China, and even South Korea, which is a gesture of strategic hedging.

In light of this, engagement with North Korea, would be seen as a calculated extension of that approach, even if limited to consultation or technical dialogue. Discreet engagement with Pyongyang could potentially provide Indonesia the opportunity to access North Korean know-how and thereby advances Jakarta’s strategic military modernisation. But still, technical focused interactions carry considerable diplomatic risk that very likely draws scrutiny from Western partners and ASEAN neighbours, given North Korea’s UN-sanctioned status. This is a situation Indonesia must navigate deliberately to pursue its defence interests without jeopardising its credibility.

Southeast Asia, of particular interest, may take a positive view given North Korea’s deliberate efforts to re-establish contact with the region in recent years. The ASEAN bloc remains committed to diplomacy and adherence to UN rules, as demonstrated at the November 2024 ASEAN Summit, in which member states expressed “grave concern” regarding North Korean missile testing and repeated demands for compliance to UN resolutions. Pyongyang’s immediate objective, presently, is clear in its pursuit of normalising defence-related diplomacy across Asia and securing new partnerships to offset its growing international isolation. With Jakarta, widely perceived as a de facto leader within ASEAN, signaling openness to North Korea-ASEAN engagement through the ASEAN Regional Forum, the region is likely to welcome cautious initiatives that facilitate constructive dialogue and uphold regional stability.

What Scenarios Could Define Jakarta-Pyongyang Ties?

Be that as it may, critics might argue that Indonesia simply will not move into substantive security ties with North Korea. Indonesia is a UN member state bound by Security Council resolutions banning arms trade and military assistance to Pyongyang. Domestic politics, moreover, could complicate such a move, with Indonesian citizens still being sensitive to human rights and non-proliferation, and any assumed to be visible closeness to an isolated regime politically risky. ASEAN’s norms of gradualism and unanimity, in the same way, mean that Indonesia could face regional pushback if its outreach to Pyongyang is regarded as undermining shared principles.

Although these concerns are valid, but they overlook certain key considerations. Indonesia’s foreign policy tradition of autonomy, reinforced by Prabowo’s willingness to engage all sides, makes similar outreach consistent with Jakarta’s broader strategy. Southeast Asia’s renewal diplomatic ties with North Korea, furthermore, demonstrate a pragmatic blend of political symbolism and strategic hedging. Vietnam and Laos are already deepening cooperation especially party-to-party, given their ideological alignment and historical reliability, with Vietnam now enhancing to defence partnership, while others still maintain cautious engagement. And by inviting North Korea deeper into ASEAN frameworks, as Indonesia extended, Jakarta can claim it is containing Pyongyang through dialogue rather than breaking away.

What might possibly happen next for Indonesia and North Korea can be assessed by probability and impact, with any security cooperation likely to be subtle and measured. First, the high-impact but low-probability scenario would involve Indonesia engaging in arms or advanced technology transfers from North Korea, which would constitute a clear breach of UN sanctions and almost certainly trigger international backlash, but such a course is improbable without a significant radical change in government doctrine. Second, a more plausible medium-probability path lies in what might be called “grey-zone” cooperation, where Indonesia sustains patterns of consultation and non-traditional cooperation with Pyongyang that fall short of explicit arms transactions. In this way, quiet exchanges on cybersecurity or maritime domain awareness could develop, producing gradual mutual understanding and potential skills transfer over time, much as Vietnam’s experience suggests. Third, the low-probability but symbolically significant option is that Indonesia’s outreach remains largely rhetorical, serving primarily to signal Jakarta’s independent stance. In this scenario, gestures of longstanding friendship continue but without translating into substantive cooperation, which represents the baseline outcome if both sides decide to play safe.

Indonesia’s Cautious Approach to Regional Stability

Realpolitik dictates that opportunities will be pursued, but legal and normative constraints must be central to Jakarta’s calculations. For Indonesia, if the goal is true strategic autonomy and national interest, the country must stay away from unclear back-channels that could raise suspicion. The government should be transparent on the scope of any North Korea engagement, for example, through public statements that consultation mechanisms are confined to non-dual-use boundaries and by submitting clear reports to the UN sanctions committee.

Indonesia’s Western partners and regional neighbours, at the same time, must approach their engagement with pragmatism. They should continuously remind Jakarta of its obligations under UN sanctions, making clear that even symbolic interactions with North Korea are bounded by diplomatic limits, and any indications of arms procurement would carry serious consequences. Nevertheless, such pressure has to be carefully calibrated because overreaction might prompt Indonesian leaders to quietly adjust their approach, seeking alternatives that avoid direct confrontation while still advancing their strategic interests.

Either way, what appears likely is that Indonesia and North Korea are rebuilding a measured, modest rapport. Regardless of the two nations’ engagement becomes remains minor or emerges as a significant factor in regional security will depend on Jakarta’s intent and the strict boundaries it establishes. History shows that Indonesia’s foreign policy often surprises, and under Prabowo’s hands-on, assertive, and more active foreign policy posture this middle power will almost certainly to assert itself more decisively in influencing regional strategic dynamics. And if properly managed, this rapprochement could allow ASEAN to draw Pyongyang into regional frameworks and strengthen stability.