In late September 2025, a year after disastrous flooding, one can see high-rise mixed-use buildings going up in a village of North Korea’s Sinuiju, from across the Amnok River, also known as the Yalu, in China’s Dandong. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

Flood recovery work was well underway in the North Korean village of Hadan in August 2024, as seen from Dandong in China. Shock troops were seen clearing flood-ravaged low-level homes at the time. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

Autumn has arrived, and the Amnok River is bustling with activity. North Korean villages along its banks are crowded with people busy with the fall harvest. Cement factories in Manpo and Hyesan operate 24 hours a day, spewing thick smoke from their towering chimneys.

A year after being devastated by flooding in late July last year, newly built 10-story mixed-use buildings have sprung up one after the other along the North Korean bank of the river, known as the Yalu River in China. Behind them, greenhouses stretch into the horizon. This is the Sinuiju Combined Greenhouse Farm, touted as the largest of its kind in North Korea, which North Korean leader Kim Jong-un visited three times this year to supervise on-site.

The older single-story dwellings and terraced fields climbing the hillsides, which were once symbols of the devastation of the famine of the 1990s known as the “Arduous March,” are clearly on the decline.

Large cargo trucks bustle back and forth on the border bridge connecting North Korea and China. Cargo volumes have noticeably increased on bridges like the Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge — a combined railway and roadway linking Sinuiju and Dandong, the largest North-China trade hub — and the road bridge connecting the city of Hyesan, North Korea’s largest inland trade hub, with China’s neighboring Changbai County.

When the Hankyoreh visited the Chinese side of the area in late September, riverside roads in the North feature a significant increase in people speeding along on electric bikes and motorcycles, and in passenger cars and SUVs. This is a stark contrast to the past, when people carrying loads on their backs or riding bicycles were the norm.

The Bank of Korea released data in late August analyzing North Korea’s gross domestic product, indicating an upward trend in economic growth rates: 3.1% for 2023 and 3.7% for 2024. The changes observed along the 1,334 km North Korea-China border, stretching along the Amnok and Tuman rivers, are even more pronounced than the Bank of Korea’s analysis suggests.

In late August 2024, flood damage to North Korea’s Ojok Island, on the Amnok River, was readily apparent from the Hushan Great Wall in Dandong, China. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

By late September 2025, the flood damage on Ojok had been replaced with newly constructed buildings ranging from three stories to seven stories high. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

Kim Jong-un’s “retaliatory recovery” projects: The transformation of Wihwa and Ojok islands

Wihwa Island, part of the North Pyongan Province, is well known to Koreans as the site of the “Wihwado Retreat,” in which the Goryeo-era general Yi Seong-gye decided to defy orders to invade Ming territory and instead stage a coup in 1388.

The island’s village (ri) of Hadan was named by North Korea’s Rodong Sinmun in late July last year as an area “severely affected by flood damage.” In late August 2024, the Paektusan Hero Youth Shock Brigade could be observed across the Amnok River, busily demolishing flooded homes and buildings. The dark, monochromatic landscape made clear that the region had been devastated by disaster.

But 13 months since, Hadan’s landscape observed from the Dandong bank of the river demonstrates that a complete transformation has taken place. Towering residential-commercial complexes, seemingly determined not to be outdone by Dandong’s high-rises, stand densely packed, each over 10 stories tall.

Signs for everyday facilities such as a pharmacy, restaurant, general store, library, “information technology promotion room” and “food supply station” all preceded by the neighborhood’s name “Hadan” hang at ground floor level. The “food supply station” is a hub where the North Korean state distributes grain. Alongside the “grain sales office” where the state sells grain at low prices established through monopoly, these are the two major legal channels for grain distribution in North Korea.

For 60 yuan, one can climb the Hushan Great Wall, which boasts a sightseeing spot known as “One Leap Across” lookout because of its proximity to North Korea. From this area, Ojok Island of Uiju County in North Pyongan Province comes into full view. Rural villages on the island, which were also ravaged in last year’s flooding, are now home to newly built residential buildings that are three to seven stories tall. The Hushan Great Wall, built on the site of the ancient Goguryeo-era Bakjak Fortress, is a mountain fortress with a complex history, as China claims it is the eastern starting point of the Great Wall.

In late September 2025, construction of dikes could be seen along the bank of the Amnok on North Korea’s Ojok Island. The dikes were double the height of the ones that preceded them. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

Paradoxes of Kim Jong-un’s rapid-fire approach to flood recovery

The flood recovery efforts spearheaded by Kim Jong-un are taking place on a massive scale, roughly equivalent to the construction of several new cities. These projects aim to complete restorations within a single year, relying primarily on the manpower of youth shock brigades and Korean People’s Army construction units.

On Ojok Island, an embankment is being raised to twice the standard height using dirt dug up from nearby fields.

Such actions are reminiscent of the “speed battles” frequently organized by the North Korea regime since Kim Jong-il became the heir apparent. Many North Korean researchers have argued that these speed battles distort resource distribution and ultimately undermine North Korea’s economic foundation.’

Could Kim Jong-un’s speed battles have a different outcome than his father’s? We shouldn’t jump to any conclusions.

Perhaps as a result of the flood reconstruction, fewer changes are apparent in border areas that were spared the ravages of last year’s flooding.

For example, two buildings being erected between a trio of round apartment towers on the banks of the Amnok River in Sinuiju look the same as when the Hankyoreh visited the border in late August 2024.

Nor have there been major changes in riverside farming communities in the village of Chungsang, Chunggang County, in Chagang Province, an area that border researchers regard as epitomizing how the Amnok River basin in North Korea is changing at present and what its future may hold.

Progress in the area amounts to repaired embankments around villages washed away in the floods. There are also several half-built three- or four-story apartments whose construction is paused at its condition 13 months ago.

Repairs are also continuing on riverside embankments designed to contain future flooding on the Amnok.

The Chinese have been raising their embankments even higher and running chain-link fences festooned with concertina wire on top. North Korea has also installed new security cameras on its chain-link fences on the riverside. The homey villages on the national border are being divided by even more mechanisms of control.

A freight train seen passing through Kim Hyong-jik County in North Korea’s Ryanggang Province in September 2025. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

From bicycles to e-bikes and motorcycles

There has been a marked increase in traffic on the North Korean side of the border, a testament to increasing economic activity there.

On a pleasure boat on Supung Lake moving upstream from a park in China, one can see electric bicycles, motorcycles, cars, vans and trucks on the North Korean side.

Train engines pulling as many as 17 freight cars loaded with coal are easily spotted at major stations along the border, such as Namyang Station, in the Namyang Workers’ District in Onsong County, North Hamgyong Province, and Wiyon Station, on the outskirts of the city of Hyesan, Ryanggang Province.

Passenger trains with cars about the length of a couple of South Korean subway cars are also a frequent sight along the Manpo-Hyesan Youth Line. These trains appear about three or four times as often as just 13 months ago.

There has been a noticeable increase in traffic in Hyesan, which is regarded as a center of both legitimate trade and smuggling between the border region and the North Korean interior.

When this reporter counted vehicles passing between Binjiang Park, in China’s Changbai County, and the Yonghung and Songhu neighborhoods of Hyesan at five-minute intervals, there were 11-15 vehicles after 10 pm on Saturday and 34-38 vehicles around 11 am on Sunday.

The make of the passenger cars was either GWM or BYD, while many of the freight trucks were made by FAW. Most were gasoline-powered vehicles from China.

The traffic there is comparable to South Korean traffic in Bonghwa, North Gyeongsang Province; Inje, Gangwon Province; and Jinan, North Jeolla Province. That is to say, traffic in Hyesan is on a level with South Korean traffic on a national highway on the outskirts of a small town or on a provincial highway near a county seat.

A researcher covering the North Korean economy for a South Korean government-funded institute noted that “the increase in traffic is remarkable, suggesting the extent to which North Korea’s economic activity is picking up.”

The Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge (rear) and the “Broken Bridge” over the Amnok (Yalu) River on the North Korea-China border, as seen from a pleasure boat dock in Dandong, China, in late September 2025. A large freight truck was headed into Dandong from Sinuiju, North Korea, while the lights in the distance belonged to newly constructed high-rises in North Korea’s village of Hadan. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

Bustling border bridges

There is also a noted increase in cargo volumes at border crossings along the rivers that form the Sino-Korean border. The Sino-Korean Friendship Bridge, which connects the cities of Sinuiju and Dandong, bustles with activity even after sunset, with large trucks going back and forth.

A long procession of large trucks loaded with cargo could be seen entering Manpo via a Jian customs station on the bridge connecting the two cities, where no truck movements had been observed in September 2023 or August 2024. The bridge between Jian and Manpo is the only bridge built by North Korea on the border following its liberation from Japanese colonial rule.

Strings of trucks, loaded with cargo, also filled the bridge between Changbai and Hyesan. However, all the cargo is going in one direction. All of the trucks going from China to North Korea are completely stuffed with cargo, but the trucks going from North Korea to China have virtually empty hauls. This is a prime example of North Korea’s trade deficit with China.

The riverside neighborhood of North Korea’s Hyesan, as seen from China’s Changbai County in late September 2025. Various vehicle models and heavy machinery could be seen parked in the area. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

Hyesan: A hub for imported vehicles?

After paying the 99 yuan entrance fee for the Changbai Millennium Cliff City, a theme park made to encourage more tourists to Changbai, and walking up its famous glass-floor bridge, one can take in the entirety of Wiyon Station, which is located at the outskirts of Hyesan, and its surroundings.

In the vacant spaces scattered throughout the area stretching from the railway station to the banks of the Yalu River, one can easily spot various vehicles and heavy machinery packed tightly into lots. A casual estimation of a dozen such areas suggests that at least several hundred vehicles were parked there. Most lack license plates, implying that the vehicles are not currently in use, but are awaiting relocation.

Article 7 of UN Security Council Resolution 2397, adopted on Dec. 22, 2017, prohibits the “direct or indirect supply, sale or transfer” of “all industrial machinery and transportation vehicles” to North Korea. Who would have bought all this machinery, and how? What are they going to use it for? Why is all this equipment in Hyesan? These are difficult questions to answer. It is worth thinking about the long-standing adage among those involved in North Korea-China trade: “The higher-ups may have their policies, but those below have their ways of getting around them.”

North Korean snacks on display at a “trade center” in China’s Jilin, near the Namyang Pavilion in China’s Jilin Province. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

Have sanctions been rendered ineffective?

Is Hyesan, which from afar gives the impression of a thriving hub for imported cars, proof that sanctions are ineffective? Is the Chinese government indifferent to implementing sanctions against North Korea? Not exactly.

A middle-aged merchant that I met at a “trade center” in Tumen, Jilin, near the Namyang Pavilion, an observatory that offers a panoramic view of Namyang Workers’ District in Onsong, North Hamgyong, offered a clue.

“Our shop probably stocks the most North Korean goods of anyone. All of the North Korean products we sell have passed customs inspections. It’s part of an official trade deal. We pay for all North Korean goods in advance, but North Korean sanctions make it difficult to transfer money. As such, we go into North Korea and pay in cash with either US dollars or yuan,” the merchant said.

This means that China is implementing UN Security Council Resolution 2270, adopted on March 2, 2016, which prohibits monetary transfers to North Korea.

The large trucks crossing the bridges between North Korea and China all have Chinese license plates and are driven by Chinese nationals. Of course, North Korea needs to pay a hefty sum for distribution costs. The fact that only Chinese cars driven by Chinese nationals are crossing these bridges reflects the Chinese government’s resolve to prevent smuggling; it is, one could say, a safety measure of sorts.

The most accurate way to describe what’s happening along the North Korea-China border is that sanctions against North Korea seem to be neither fully implemented nor fully disregarded, but rather somewhere in between.

The customs office in Dandong was bustling with people just after opening when the Hankyoreh visited in late September 2025. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

North Korea-China trade restored, imbalance strengthened

As evinced by the activities at the border, North Korea-China trade is on the rise. Statistics provided by China’s customs authority indicate that North Korea’s imports from China totalled approximately US$1.22 billion in January to July of 2025, jumping 33.6% year-on-year from US$914.08 million. Exports to China were US$245.07 million, showing a year-on-year increase of 24.3% from US$197.16 million.

North Korea’s imports from China are quintuple its exports to its neighbor. While trade between the two countries is rapidly returning to levels seen before sanctions were placed on North Korea, the imbalance in trade is worsening. This is why Kim relayed his hopes that the two countries would advance mutually beneficial economic and trade cooperation during his summit with Chinese President Xi Jinping on Sept. 4.

But Kim faces an uphill battle to make these hopes a reality. Sanctions are a fundamental constraint on North Korea’s economy, but its lack of competitiveness when it comes to products is also a problem to be reckoned with.

“North Koreans barely manage to meet their delivery deadlines. I’d say that they manage to fulfill their promises one in ten times. Young tourists these days are more partial to goods in smaller packages, so we request that they make products in that size, but they’ve remained completely oblivious,” a middle-aged merchant working at the trade center told me.

High logistics costs and a stunted approach when it comes to consumer preferences reveal that North Korean goods are treated more like souvenirs than commodities.

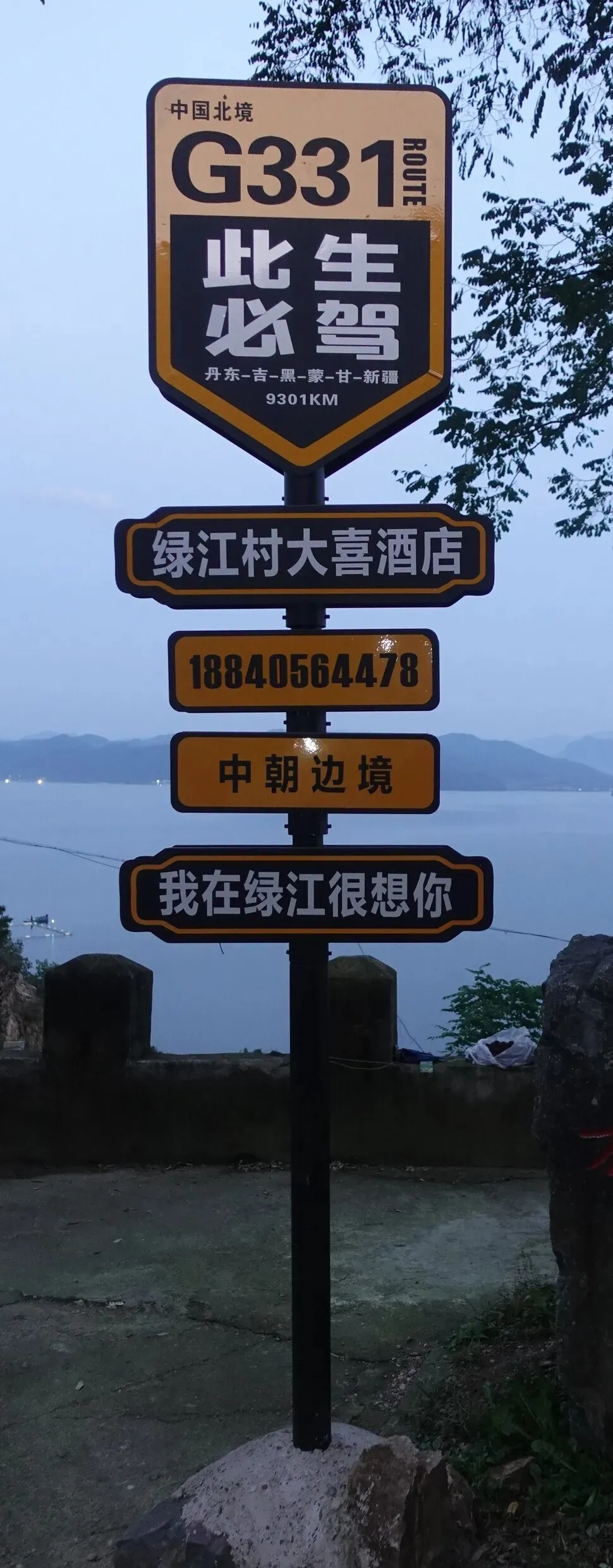

A hill on the Chinese side of Supung Lake bears a sign reading “G331 ROUTE 此生必駕, Must go in your life.” (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

A young Chinese couple snaps photos from Namyang Pavilion in China’s Jilin Province, which overlooks North Korea’s Namyang Workers’ District in North Hamgyong Province. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

Cruising down G331: The ideal trip of China’s Gen Z

To travel the 1,334 km of the Sino-Korean border while keeping North Korea in view requires a trip down China National Highway G331. China’s local and central governments appear to be trying to convert the highway into a tourist attraction in order to boost the tourism income of the three provinces of Northeast China (Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang), which are relatively underdeveloped.

National Highway G331 stretches from Dandong, on the western border with North Korea, to Yanji, Inner Mongolia, Gansu, and all the way to Xinjiang — a northern route that spans 9,301 km. The highway feels like a mix of South Korea’s National Route 7, which runs along the coast of Gangwon Province, and a DMZ pilgrimage. It’s longer than the Trans-Siberian Railway (9,288 km).

Along the trip, one frequently encounters a yellow sign that reads “G331 ROUTE 此生必駕, Must go in your life.” On a hill near Supung Lake in North Korea’s Usi County, Chagang Province, there is a sign that reads, “I am thinking of you at the Yalu River.” At key points along National Highway G331, construction for sightseeing spots, similar to the size of highway rest stops along highways in South Korea, is underway.

Since Xi Jinping took power in 2012, the Chinese government has devoted considerable resources to its “red tourism” project designed to bolster national socialist pride. The marketing campaign around National Highway G331 appears to be an attempt at adding an element of Gen Z cool.

The flag of China flies on the Chinese side of the summit of Mount Paektu, known as Mount Changbai in China, in late September 2025. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

On Sept. 28, China unveiled its Shenyang-Baihe high-speed railway, which links Shenyang, the largest city in Northeast China, to Mount Paektu, known as Mount Changbai in China. It travels 430.1 km in under two hours, cutting the travel time between the two areas in half. The railway is a part of a strategic initiative to boost tourism around Mount Paektu. Since 2016, Kim Jong-un has worked to convert the Mount Paektu tourism and culture district centered around Samjiyon into a “global mountain resort.”

How will the effort to boost tourism along National Highway G331 and the opening of the Shenyang-Baihe railway affect the economy along the North Korea-China border? Will it result in the Sinicization of tourism to Mount Paektu, or will it synergize and boost North Korean and Chinese tourism around the mountain? Time will tell. However, it’s doubtful whether North Korea will be able to effectively utilize the massive wave of Chinese capital and human resources entirely to its benefit.

Which begs the question: Why hasn’t North Korea aggressively incorporated Chinese tour groups to Mount Paektu?

“Tours to North Korea haven’t happened yet. They accept Russian tour groups, but not Chinese ones. I don’t know why,” an employee at a travel agency in Northeast China grumbled.

The New Amnok/Yalu River Bridge as seen from Dandong, China, in late September 2025. On the right is North Korea’s Sinuiju. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

The torturous hope surrounding the New Amnok/Yalu River Bridge

The New Amnok/Yalu River Bridge is a barometer for Beijing-Pyongyang relations. At 3,016 meters, it is the largest and longest suspension bridge that traverses the border and was completed in 2015. Yet 10 years later, it still has not opened.

“People involved in trade with North Korea say that the bridge will open in 2026, but people have been saying that for 10 years now,” an employee at a travel agency in Dandong said glumly.

Construction on what was supposed to be a customs building at the northern end of the bridge stopped at land-clearing.

The calculations of North Korea and China regarding cross-border economic cooperation run several layers deep. The agreement between the late North Korean leader Kim Jong-il and former Chinese President Hu Jintao in May 2010 to create an “economic cooperation region” on Hwanggumpyong Island and Wihwa Island has essentially been scrapped. Kim Jong-un is currently directing the construction of a massive greenhouse farm on Wihwa that spans the size of 625 soccer fields. The building for the management commission of the economic cooperation region stands on the windy grounds of Hwanggumpyong Island like a ghost.

A train runs along the Korea-Russia Friendship Bridge as seen from China. Behind the bridge, abutments for a road bridge can be seen under construction. (still from video from Baidu)

Access to the road bridge connecting Russia and North Korea denied

In June 2024, during Putin’s visit to Pyongyang, North Korea and Russia agreed to construct a road bridge over the Tuman (Tumen) River. Construction began on April 30 of this year. If you pay 50 yuan to go to the top of the observation tower in the village of Fangchuan in Hunchun, a county-level city in Northeast China that borders both North Korea and Russia, you can look down and see the construction site 400 meters downstream from the Korea-Russia Friendship Bridge, a railway bridge from the Soviet era.

However, it’s incredibly difficult for foreigners to visit Fangchuan, and they’re basically forbidden from the observation tower. Reportedly, this de facto ban began at the end of last year, and no official reason has been offered. While it is a point where the borders of North Korea, China and Russia meet, it’s unlikely that national security sensitivity is the only reason for the ban.

In 1860, near the end of the Qing Dynasty, China ceded territory in Manchuria to Russia that is now known as Primorsky Krai. China, therefore, still doesn’t have port access to the East Sea. From Fangchuan, one needs to follow the Tumen 16.93 km along the North Korea-Russia border to reach the East Sea.

But when looking at the Russian construction plans, the height of the bridge pier is around 7 meters from the water level, making it no different from other railroad bridges. That is, even with North Korean and Russian cooperation, Chinese ships cannot access the East Sea.

China’s “long-cherished dream” of access to the East Sea, as former Chinese President Jiang Zemin described it, is still out of reach. The point where North Korea, China and Russia meet is a gauge for determining which way trilateral relations will go, so the shutdown of Fangchuan’s observation tower is a considerable indication of a standstill.

Once construction of the road bridge is complete, connecting North Korea to the Russian locality of Khasan, many people expect North Korea-Russia trade to greatly increase.

Yet Russian experts remain aloof in their appraisal of the project. Anna Bardal, leading researcher at the Economic Research Institute of the Far East Branch of the Russian Academy of Science, whom I met on Sept. 9 in Vladivostok, said harshly, “The Tuman road bridge is, like other railway bridges that came before, merely a symbol of Russia-North Korea relations that is designed to send a signal to the international community. There is absolutely no economic feasibility tied to it.”

Propaganda slogans could be seen in the Hoha Workers’ District of North Korea, which houses the March 5 Youth Mine, in September 2025. (Lee Je-hun/Hankyoreh)

Kim Jong-un’s political centralization along the banks of the Amnok and Tuman

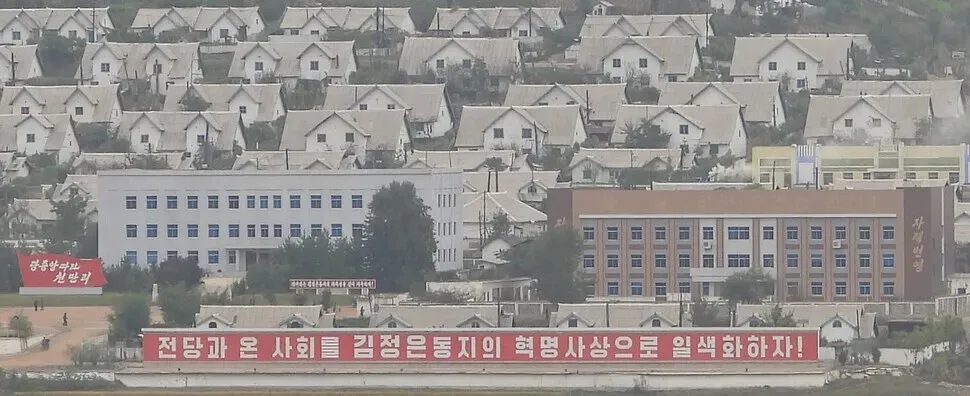

There is another change happening in the North: political slogans. Nearly all national slogans are focused on Kim Jong-un. The slogan “Long Live Juche Choson and General Kim Jong-un, the Sun” can be found at the Sinuiju port near the lower Amnok, in Manpo and Hyesan, and on the outer walls of Namyang Station in Northern Hamgyong Province, on the banks of the Tuman.

The slogan “Let’s unite the entire party and the whole of society under the revolutionary ideology of Comrade Kim Jong-un” was written on a banner hung from the outer wall of a hotel in Hyesan, located in the middle of the Hoha Workers’ District in Chunggang County, Chagang Province, where the March 5 Youth Mine is located.

This could be an indication that North Korea will codify “Comrade Kim Jong-un’s revolutionary ideology” in the party’s official bylaws during the 9th Congress of the Workers’ Party of Korea, which is expected to be held in January 2026. If that happens, Kim Jong-un thought will be placed on the same level as “Kimilsungism-Kimjongilism,” which is officially the party’s sole guiding ideology.

By Lee Je-hun, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]