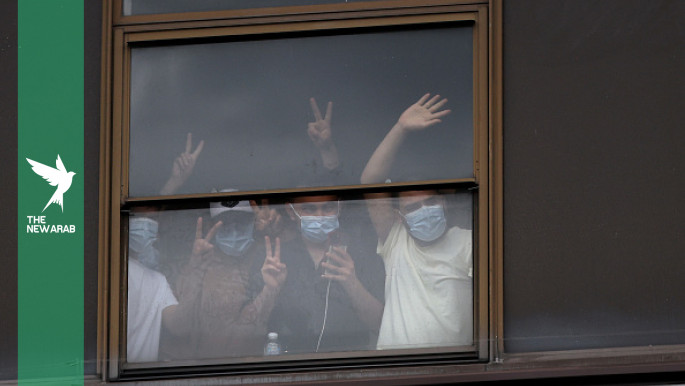

Migrants wave give a peace signs from a window of the Barbican Thistle Hotel as protest from a mix of including anti-immigration, anti-fascist and stand up to racism groups gather outside on 2 August in London [Getty]

Inside Britain’s run-down hotels, refugee families live on cold meals and a weekly allowance of barely £10 (around $13), while profits pour into the accounts of private companies that have turned government asylum contracts into a lucrative business.

The major companies at the heart of this system are Clearsprings Ready Homes, Mears Group, and Serco. Each holds long-term Home Office contracts to provide accommodation for asylum seekers, including the use of hotels.

Since 2019, the three firms have collectively made hundreds of millions of pounds in profits, with Clearsprings alone reportedly earning over £180 million in profits and dividends shared among its directors.

Mears and Serco have also reported substantial gains, despite ongoing criticism of the poor conditions inside the properties they manage.

As of June 2025, a total of 111,084 people had claimed asylum in the UK, marking the highest number on record and a 14 percent rise compared to the previous year, surpassing the previous peak in 2002.

Around 32,000 asylum seekers were being housed in hotels across the country, reflecting a growing dependence on temporary accommodation that has proved highly profitable for private contractors.

Although the Home Office says it has agreements for companies to return profits above certain limits, the sector remains deeply lucrative, fuelled by rising asylum numbers and expanding government spending on emergency housing.

A system that ‘does not work’

“The UK’s current asylum accommodation system does not work,” Tom Martin, director of City of Sanctuary Sheffield, told The New Arab. “Instead of safe and secure temporary accommodation, people seeking asylum are forced to live in unsafe, overcrowded and occasionally dangerous settings for prolonged periods.

“We have seen countless examples of accommodation being used that would not pass a building inspection. Nobody, regardless of where they are from, should be forced to live in accommodation where rainwater pours through electrical sockets, mould covers the walls, or rats and mice share the kitchen with residents.”

Martin said the system had become “a lucrative source of income for a small number of private contractors and landlords, some of whom are among the UK’s wealthiest people”.

“These companies are awarded multi-million-pound contracts, often without proper oversight or competition, to provide accommodation and services. In many cases, the services delivered are substandard, yet costs continue to balloon. This setup rewards private firms for contracts that are completely unfit for purpose,” he said.

He argued that reform “should be led by local authorities and non-profit organisations that are accountable to their communities”.

“Housing provision should be local authority-led and both rooted in and accountable to their communities,” he said. “Local councils, housing associations, and non-profit organisations have a deeper understanding of local needs and are better positioned to coordinate with health services, schools, legal aid providers, and integration support.

“Crucially, under this model, any surplus or savings could be reinvested back into local communities, improving housing stock, social services, and integration programs that benefit both asylum seekers and local residents.”

He added that the current system “has declined due to years of outsourcing and short-term thinking. Restoring a humane and effective accommodation system means investing in long-term, sustainable solutions that see people seeking asylum as human beings deserving of dignity – not as logistical problems or political scapegoats.”

‘Millions in taxpayer-subsidised profit’

Zoe Dexter, Housing and Welfare Manager at the Helen Bamber Foundation, said thousands of people, including survivors of trafficking and torture, were placed in “often squalid hotels” while waiting for their asylum claims to be processed.

“Living in unhygienic and crowded spaces, putting up with substandard food and living on an allowance of £9.95 per person per week is an everyday reality for many, as they are not allowed to work while waiting for a decision,” she told The New Arab. “This is compounded by the sheer length of time they spend in these conditions. Helen Bamber Foundation has had clients whose children have spent most of their lives in a hotel room. Legal action can often be the only effective way of ensuring our clients are moved to somewhere more suitable.”

“For-profit companies earn millions in taxpayer-subsidised profit, while deliberately overseeing and delivering a housing system which dehumanises and frequently further traumatises vulnerable people seeking asylum,” Dexter added.

The foundation’s research found that people forced to live in asylum hotels had experienced “significantly higher levels of distress and depression compared to people living in alternative accommodation”.

“Concerningly, this study also found that hotels often create new mental health difficulties as many participants described developing severe depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation,” Dexter said. “Families with children particularly experience an adverse impact on their mental health as parents are unable to provide adequate care for their children and experience a diminished sense of parental autonomy, and children often struggle with food and having nowhere suitable to play.”

She said the isolation of hotel life is worsened by “the inappropriate treatment they often face from untrained hotel staff”.

“What we need is better quality initial decision-making and proper investment in the justice system,” she said. “Getting it right first time more often should be the starting point, not rushing people through a broken system. Efficient and fair management of the asylum system will reduce and then eliminate the need for hotels and large accommodation sites to be used.”

Spending spirals, accountability fades

Data from the National Audit Office show that the cost of asylum accommodation contracts has risen from £4.5 billion to £15 billion, mainly due to the growing reliance on hotels instead of permanent housing, in a choice that benefits companies but costs the state more.

Layla Hussain, advocacy officer at the Refugee and Migrant Forum of Essex and London (RAMFEL), told The New Arab that what was unfolding was an “asylum economy”, where “the suffering of vulnerable people becomes a profitable investment opportunity”.

“Refugees are paying the price for a system that is meant to be humanitarian but has become a commercial model where revenues grow as suffering worsens,” Hussain said. “Meanwhile, public discourse portrays asylum seekers as a burden, when in reality it’s private firms who benefit most from public spending.”

She noted that transparency in the sector is “almost non-existent”. Since 2019, Clearsprings, Serco, and Mears have monopolised housing contracts worth around £4 billion ($5.3 billion) over ten years.

Government spending has far exceeded forecasts, Hussain added, with £1.7 billion ($2 billion) allocated in the first seven months of 2024 alone – £1.3 billion ($1.7 billion) of which went solely to hotel operations. The three companies collectively earned £380 million in profit between 2019 and 2024, despite repeated criticism of conditions and violations at immigration sites.

“It’s a closed system where failing companies keep getting contracts without genuine accountability,” she said.

Hussain also criticised “misleading” government claims about reducing hotel use. Labour ministers announced a drop from over 400 to 200 hotels, but official data show a smaller decrease, from 213 in July 2024 to 210 a year later.

She said reform was “essential for justice and efficiency”, urging the government to redirect funds toward community housing through local authorities and create “Welcome Hubs” to help refugees integrate.