It is happening right now, right on Broadway, every weekday. Undocumented immigrants line up to enter 26 Federal Plaza. They walk to the elevators, pass the death-stare portrait of President Donald Trump, and hit the button for the federal immigration courtrooms located on the 12th and 14th floors. When the doors open, they enter harshly lit hallways where ICE agents mill around in black balaclavas waiting to take people away. The agents have a list. No one knows how you end up on it. Around the country, Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents are carrying out Trump’s promised roundups, staging armed raids designed to create muscular social-media spectacles and rattle cities like New York, where nearly 40 percent of the population is foreign born. Since late spring, though, the strategy in New York has shifted to easier pickings. ICE agents are focusing on the willing and unwitting people who present themselves at three immigration courts, the largest of which is located inside the Federal Plaza building, a 41-story slab of an office tower.

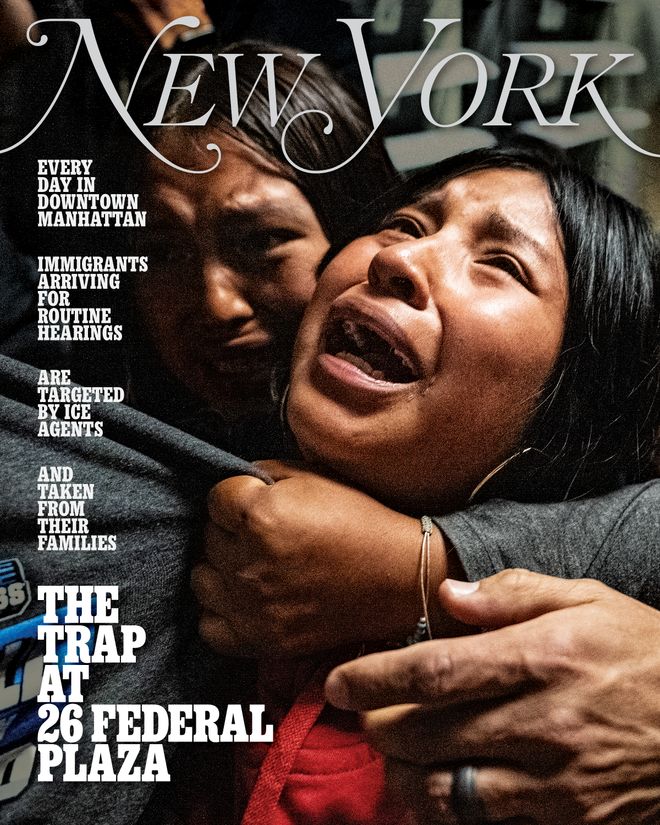

The Trap at 26 Federal Plaza

The agents who haunt the hallways seem to follow their own secret rule book, staying out of the way of the immigration judges, who go about their legalistic business in drab little courtrooms as if nothing were amiss. (The judges are Justice Department employees, not members of the judicial branch, so they can be fired and, under Trump, sometimes are.) The rulings the judges make seem to have little bearing on who is arrested, anyway. ICE is invoking a sweeping — and legally shaky — interpretation of its right to detain people as their cases work their way through the system. These immigrants in no way resemble the “worst of the worst,” the criminals Trump promised to deport first. They are the asylum seekers, the rule followers. They go into the federal building holding papers — bureaucratic immigration forms and court summonses — hoping for a measure of due process. Some leave the courthouse with a hearing date set months or years from now. Others disappear into ICE’s prison system.

Even in the best of times, the process of deciding who gets to stay in the U.S. and who has to leave is dysfunctional. Now, it’s been injected with cruelty. When the courthouse arrests first began, they were met with outrage and street protests in Manhattan, but the scenes both inside and outside the building have since become routine. A group of regulars still shows up: immigration lawyers; courtroom observers who sit in on hearings; spiritual counselors, including an Argentine pastor, Father Fabián Arias, who assists family members of the detained. There is also a crowd of mostly freelance photographers and videographers who have secured permission to roam the hallways, deemed public space by an act of inscrutable government transparency. (At most federal district courthouses, press access is much more constrained.) The photojournalists watch the agents carefully, waiting for them to move with sudden force.

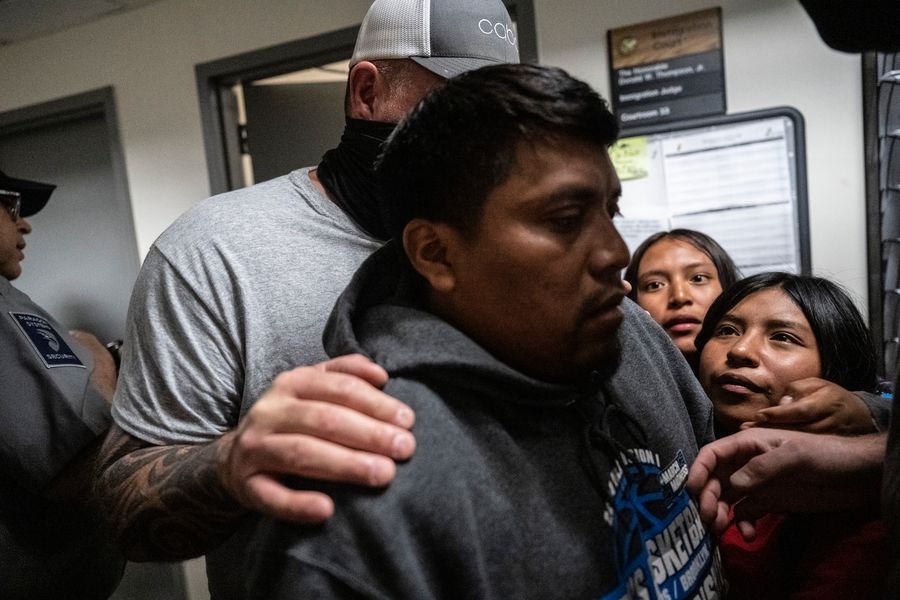

August 12: Funneling a detainee to detention at 26 Federal Plaza.

The building’s hallways — the danger zone — are laid out in an H-shaped pattern with an elevator lobby in the middle. Courtrooms and waiting rooms are spaced along the corridors, which are lined with bulletin boards splashed with faded announcements and menacing flyers that read MESSAGE TO ILLEGAL ALIENS: A WARNING TO SELF-DEPORT. The masked agents cluster along the walls and at the terminal points of the corridors. In their dress, they go for varying degrees of intimidation: Some are relaxed, wearing casual clothes, neck gaiters, and official badges on chains; others, in tactical vests, cover even their eyes with sunglasses, adopting the look of faceless enforcers. Many appear not to work for ICE but are detailed from other federal law-enforcement organizations. Nearly a quarter of the nation’s FBI agents, for instance, are now on immigration duty. Groups of agents rotate in and out. For a while, there was a contingent of officers from the State Department’s Diplomatic Security Service whom observers found to be suitably courteous. Some agents are ostentatiously callous. A few have notorious reputations among the outside observers. A woman they call “Icicle,” who seems to be a supervisor, stands out because she is one of the few who declines to cover her face. She sometimes berates the photographers, telling them to “get a life.” There’s a rough man they have nicknamed “King” because he behaves with even more impunity than the others.

The observers say there is often a crushing rhythm to how detentions go down. Migrants appear before a judge and are given a date for another hearing, leaving them hopeful and thinking they are free to go. Then, the moment they step outside the courtroom, they are arrested and hustled away. Detainees are usually taken down a stairwell to cells on the building’s tenth floor, a holding area so miserable and overcrowded that a federal district court judge recently called its conditions potentially “unconstitutional and inhumane.” (In a statement, an ICE spokesperson said, “ICE operates these hold rooms and holding facilities in strict accordance with its National Detention Standards [NDS] to ensure the safety, security, and humane treatment of individuals in custody.”) From there, detainees are conveyed by bus or van to ICE detention facilities in Brooklyn; Newark, New Jersey; or other nearby locations, then often flown to privately contracted prisons in Republican-dominated states such as Florida, Louisiana, and Texas, where their cases are transferred to fast-working and unsympathetic local immigration judges.

There are currently over 60,000 immigrants being held in detention nationwide, an increase of close to 50 percent since Trump took office. (The ICE spokesperson said the “volume of apprehensions and subsequent detentions is a direct result of individuals choosing to break the law,” adding that “all ICE arrests are made in compliance” with legal processes.) About half of the at least 2,300 people detained in New York between January and June were taken after routine check-ins and court hearings, according to federal data. In the past, for reasons both statutory and practical, only a small minority of people without permanent status were subject to detention and the rest were paroled or classified in a way that gave them some legal protection to work, drive, and otherwise go about their lives as they tried to get a green card. “What this administration has done,” says Benjamin Remy, an immigration attorney with the New York Legal Assistance Group, “is it has broadened the scope to encompass all of these categories so anyone here without lawful status can be detained without a hearing and without a bond.” The ACLU and other civil-rights groups have been fighting these assertions of detention power, and federal judges and other authorities in various jurisdictions have issued contradictory preliminary rulings on the issue, leaving a muddle. While the lawyers argue, the arrests go on, day after day.

On a brisk October morning, I visited the Manhattan immigration court with Stephanie Keith, a photographer who has been documenting the detentions since they started, and whose work you see here. Outside a courtroom at a far end of the 14th floor, a 2-year-old boy with long curly hair and giant brown eyes was hopping around the water fountain, oblivious to the looming presence of men in black. His father fetched him, and he toddled back into the courtroom, which was situated behind a waiting area with hard maroon plastic seats. I waited there and listened as his mother finished a hearing before Judge Kyle Dandelet, her fourth since 2023. The 34-year-old woman and her husband migrated from Ecuador with her two older sons in 2022, crossing into Texas after taking the perilous journey through the Darién Gap and Mexico. The family — including the child at court, who was born in the U.S. — was living in Newark, where both parents worked in a factory. The mother was asking for asylum, claiming she had fled a gang back home that wanted to murder her and that her family would be in danger if they were deported. The judge set her next hearing date for September 2026.

Out in the hallway, agents were massing, though neither the mother nor I could sense that as she put her boy in a stroller. She smiled at me, looking relieved, as her husband pushed the stroller through the doorway ahead of her. At the threshold, a masked female agent moved forward quickly and placed her body between the husband and wife, and a second agent, a man, maneuvered the woman against the hallway wall. There was a kinetic jolt and the photographers rushed forward. A young unmasked agent dressed like Elon Musk — black hoodie, black baseball cap, wraparound shades — came from a position outside the scrum and blocked my view. Tucked into his jacket was a badge that identified him as a special agent of the Treasury Department: maybe a tax investigator playing a tough guy.

“Ayúdenme” — “Help me” — the mother cried.

The second agent addressed the woman in Spanish, saying they needed to speak in a private room, away from the cameras.

“Por favor,” she pleaded, then she said in Spanish, “They’re going to kill my son.”

“Let her kiss her baby!” shouted one of the volunteer observers, a middle-aged blonde woman. The agents ignored the cries and rushed the mother toward a stairwell a dozen or so steps to the right of the courtroom. From there, the woman was taken to a holding cell. Within days, she would be transferred to the South Louisiana ICE Processing Center, a facility run by the private-prison contractor Geo Group, presumably to await deportation.

The blonde observer ushered the dazed father to the elevators and mashed the DOWN button. The photographers followed in a swarm, shooting as the father fought back tears. He had picked up his son from the stroller and was holding him tight. The little boy looked confused, then he saw the cameras and knew what he was supposed to do for them. He smiled. Then his father took him downstairs, out to the concrete plaza, and the agents suddenly vanished from the hallways, done with their work for the day.

— Andrew Rice

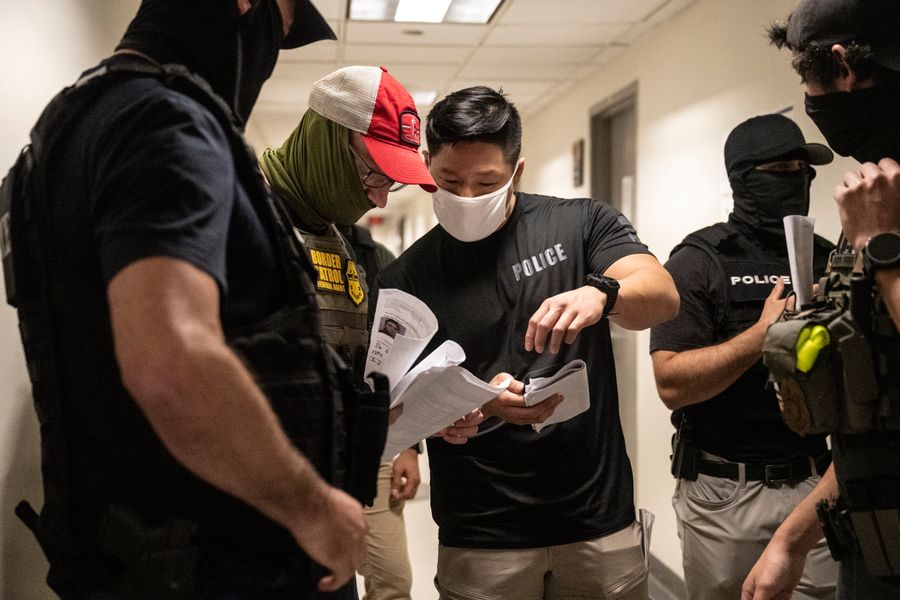

July 14: A federal agent checking a list moments before detaining a woman.

July 16: Federal agents consulting dossiers of people subject to arrest.

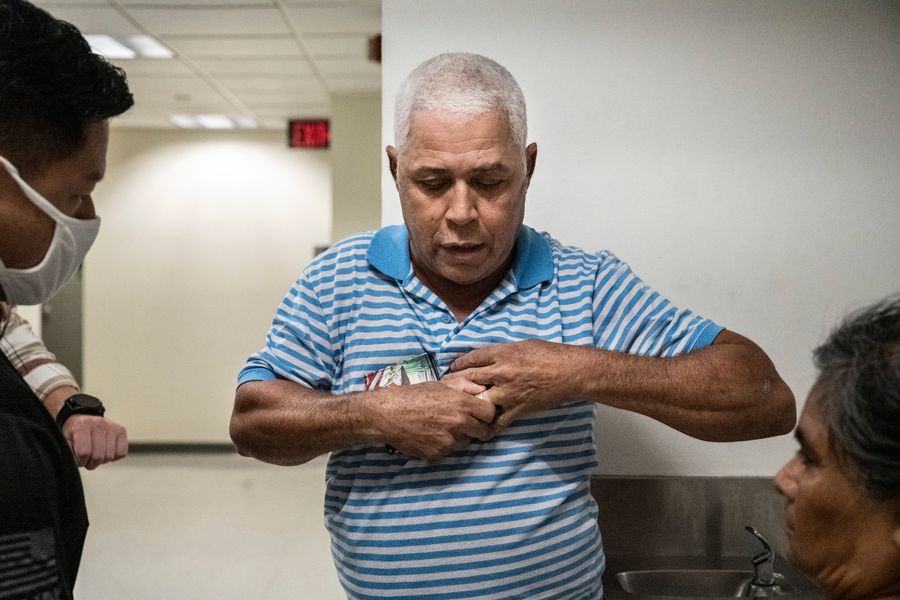

August 7: A wedding ring being removed by a detainee.

August 25: Natalia had tried to convince her husband, Jamal, not to go to his appointment in person. She had heard that ICE agents were detaining people, mostly men. But as a Muslim, said Natalia, Jamal felt he had to obey the law. He said that if he were arrested, all he wanted to do was say good-bye to their 8-month-old son. “I won’t move,” she promised. As she waited for him to finish his court hearing, Natalia overheard ICE agents call for backup because “this is going to be a tough one.” She watched an agent position herself right outside the door to the courtroom. Once Jamal emerged, said Natalia, “the whole world came crashing down on him.” As officers tackled him to the ground, he clung to the baby carriage; they ripped him away. “It was one of the most horrific things I’ve ever seen,” said a lawyer who was present.

July 11: The patterns of certain federal agents who detain immigrants inside 26 Federal Plaza — both ICE officers and those detailed from other law-enforcement agencies — have become well known to the observers, lawyers, and photographers who are typically at the courts. One officer, nicknamed “Icicle” by the regulars because of her small frame, is known to be “extremely, extremely volatile,” said a lawyer who has interacted with her several times. She taunts photographers and lawyers, according to multiple people who have seen this happen. A month ago, when a federal judge issued a temporary restraining order prohibiting ICE from holding people in inadequate conditions in the tenth-floor detention area, she complained loudly that the officers didn’t have anything to do and “wanted more people to arrest.” On one occasion, she was arresting someone and an advocate told that person they had a right to remain silent. The agent turned to the advocate and said, “No, they fucking don’t.”

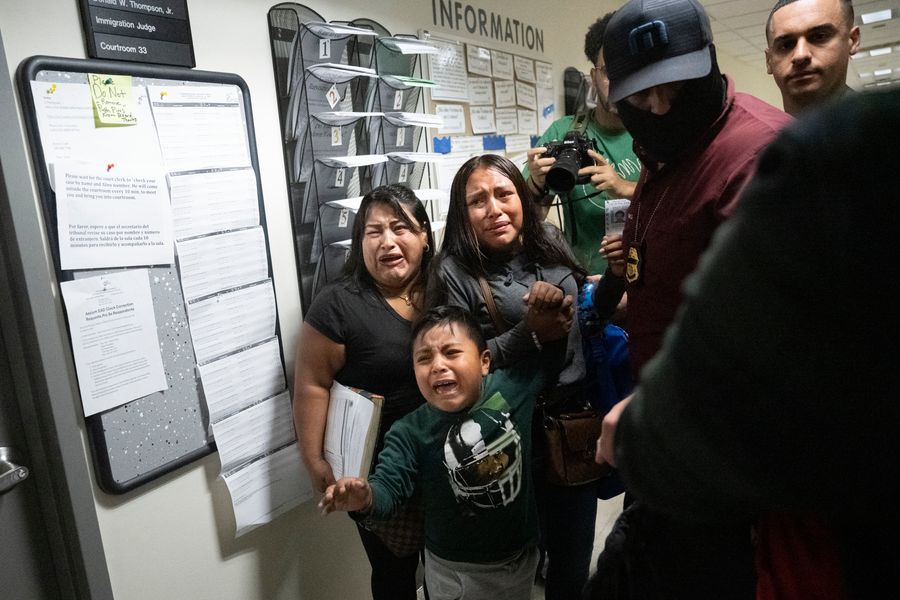

August 26: “I heard screaming,” said a court observer who was present on the day Cocha’s husband, Luis, was detained. Their three children, 7, 13, and 15, clung to him as he was swarmed by agents in the hallway. No one explained to Cocha what was happening or where her husband was going. “My daughter is distraught. They took their father away,” Cocha told reporters. “I don’t know what to do.” Eventually, the agents peeled the children off Luis. “They just sort of collapsed,” recalled the observer, who sat with the family on a stoop outside the courthouse as Cocha called relatives. “They took him,” Cocha said into the phone over and over again.

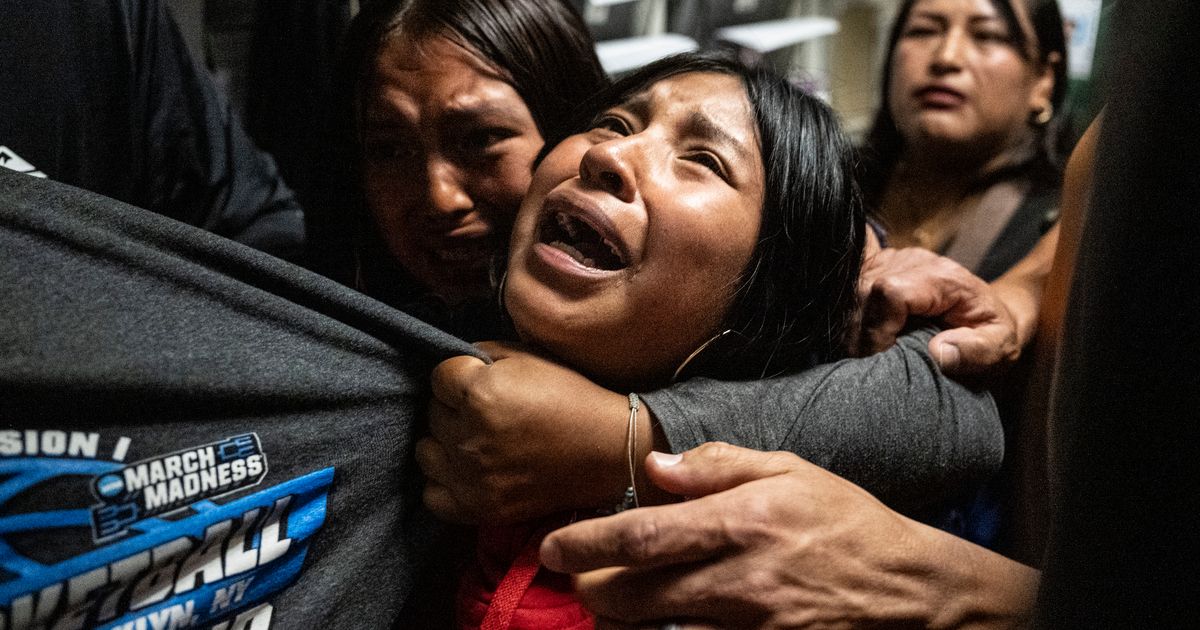

September 25: Monica and her husband were overjoyed as they left their hearing; they had been told to come back in 2026. The couple and their two children had only recently moved into an apartment after living in a shelter, and their lives were beginning to stabilize. But as they stepped into the hallway outside the courtroom, federal agents “yelled at us to get against the wall,” Monica recalled. She was bewildered. “I didn’t know if they were taking him or me,” she said. Once she realized the agents were arresting her husband, she pleaded, “If you’re going to take one of us, take all four of us.” The agents pushed her against a wall, pulled her hair, shoved her children; she was eventually thrown to the ground by a federal officer who was later suspended. “My daughter apologized to me afterward,” Monica recalled. “She said, ‘It’s my fault they took him. I should have held on tighter.’” The suspended officer was reportedly reinstated within days.

July 16: In the months leading up to his asylum hearing, Lilian’s brother, Carlos, became quiet. He was usually funny and playful, but as his anxiety mounted, “he wasn’t the same,” she said. Lilian, Carlos, and their sister, Porfiria, knew that ICE agents were making arrests in the courthouse, but they arrived at his appointment with hope. “He had nothing to hide,” Lilian said. At first, all seemed well; the judge set Carlos’s next court date for 2029, and the sisters were relieved. Then, as they left the courtroom, agents attempted to grab Carlos. The sisters latched on to him, one on each arm. The agents threw Porfiria to the ground, injuring her knee. “It was horrible,” Lilian said. “I can’t get over it. I relive it every time I see another arrest.” Carlos was held for 15 days, then released when a judge granted a reprieve. He told Lilian that while he was in custody at Federal Plaza, an agent pressed a newspaper photo of his crying face against the glass wall of the holding cell, mocking him.

September 11: Family members of the detained have little clarity about what to do after their loved ones are taken. An arrest can occur so suddenly the family often doesn’t realize what’s happening until it’s over. They sometimes think their loved one is right behind them until “they look back and the person’s not there,” said a photographer who has been documenting the detentions. Court observers and lawyers usher devastated family members out of the building. Spiritual counselors offer emotional support and connect families to legal services. Immigrant-rights organizations do what they can to petition for the release of detainees. Still, families don’t know what will happen next. After his loved one was taken, Milton seemed frozen in place, saying, “Where is she? Where is she?” Eventually, photographers informed him she had been detained.

Additional reporting by Isabella Ramírez

Thank you for subscribing and supporting our journalism.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the October 20, 2025, issue of

New York Magazine.

Want more stories like this one? Subscribe now

to support our journalism and get unlimited access to our coverage.

If you prefer to read in print, you can also find this article in the October 20, 2025, issue of

New York Magazine.

One Great Story: A Nightly Newsletter for the Best of New York

The one story you shouldn’t miss today, selected by New York’s editors.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice