The ecumenical rumor mill is churning, and right now, it’s saying the Vatican may be on the verge of a dramatic move against one of its most powerful and controversial groups.

According to recent reporting, newly enthroned Pope Leo is set to approve reforms that would effectively gut Opus Dei, the highly controversial conservative ascetical Catholic organization known to the masses by its scandalous portrayal in the bestselling novel and film The Da Vinci Code.

The proposed changes, aimed at dismantling the group amid its history of alleged abuse, spiritual manipulation and coercive control, would strip the order of its leadership and authority over its 95,000 worldwide lay adherents.

But as the dust settles, a critical question has arisen: Will these changes to church law (called “canons”) actually work, or will the group force its practices underground and attempt to defy the titular Vicar of Christ on Earth himself?

“Opus Dei is a global institution within the Catholic Church founded in 1928 by a controversial Spanish priest, Josemaría Escrivá.”

Opus Dei (Latin for “work of God”) is a global institution within the Catholic Church founded in 1928 by a controversial Spanish priest, Josemaría Escrivá. Its central teaching is the call to holiness for all people and that anyone —not just priests, monks or nuns — can become a saint.

The apostolic brief commissioned at Escrivá’s beatification (the proclamation of his sainthood) noted: “The universality of the call to full union with Christ implies that any human activity can become a place for meeting God.”

Pure intentions aside, the group’s methods are — by any objective measure — far from ordinary.

Chief among the group’s many controversial and contested practices is “corporal mortification” — the physical self-punishment of the human body to further personal holiness. This includes the use of a spiked chain worn on the thighs and a small whip for self-flagellation to be employed during moments of temptation.

There also have been long-standing criticisms about the group’s approach to “spiritual direction” — an ancient practice grounded in the tradition of the church of having a senior Christian leader and mentor give direction, counsel and insight to another’s spiritual walk. Some of those who have left the group have claimed totalizing and coercive control, with spiritual directors dictating members’ careers, romantic and sexual partnerships, and even the books, music and movies they access.

According to various reports, it is this last point that has drawn the pope’s concern (or ire) more than anything else.

Enter the invigorating task of amending and reading ancient church law.

Structurally, Opus Dei is a “personal prelature,” a sort of global diocese without geographic boundaries that reports directly to the Vatican and the pope. The “personal” descriptor also applies to members: they enter the society and take voluntary vows of personal obedience to their directors.

This is in stark contrast to the way things normally work in communions that have episcopal leadership, including Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Anglican, Lutheran and even some Methodist groups where clergy and lay ministers state their allegiance to the bishop who oversees the diocese or network of churches entrusted to their episcopal care.

Herein lies the rub and the potential locus of reform.

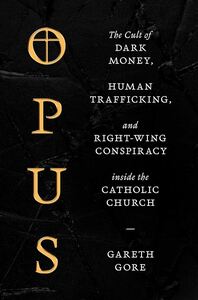

According to Gareth Gore, author of OPUS: The Cult of Dark Money, Human Trafficking, and Right-Wing Conspiracy inside the Catholic Church, the pope is considering disbanding the group’s existing structure and segmenting it into three new ecclesiastical entities with distinct rules and disciplines:

According to Gareth Gore, author of OPUS: The Cult of Dark Money, Human Trafficking, and Right-Wing Conspiracy inside the Catholic Church, the pope is considering disbanding the group’s existing structure and segmenting it into three new ecclesiastical entities with distinct rules and disciplines:

A clerical prelature exclusively for priests who have been ordained within the movement

A separate society for priests not ordained within the movement but associated with it

A “public association” for its vast lay membership

This would mean the clerics and leaders of Opus Dei would lose all canonical jurisdiction over laypeople and return this responsibility to lay members’ local bishops.

Herein lies the catch. Critics, including many former members Gore has worked with, argue the Vatican’s solution fundamentally misunderstands how Opus Dei operates. The organization’s power isn’t just derived from canon law; it’s rooted in a quasi-idolatrous devotion to Escrivá, who was declared a saint in 2002.

Members are taught that Escrivá’s vision and meticulously detailed internal rules —governing everything from prayer life to finances — were received directly from God. For the most devout, also called “Rad Trads” (Gen Z shorthand for “radical traditionalist” Catholics who do not recognize the authority of the pope and believe the chair of St. Peter is empty), devotion to the cult of a saint likely will supersede any new directives from Pope Leo.

As one former celibate member wrote, “Telling people they are free to stay or leave means little when they have been manipulated to believe that ‘freedom’ is doing whatever the directors tell you. That belief doesn’t change with new statutes from the Vatican.”

This sentiment was seemingly reinforced by Opus Dei’s current leader in a recent letter to members, where he urged them to remain unified and loyal to the “spirit” of the group and maintain “unity with the origin” — a subtle message to stick to Escrivá’s original vision, regardless of “external difficulties.”

The innuendo is palpable: Popes may come and go, but the real hard work it takes to be a saint goes on forever.

Further complicating the matter is this: If the Catholic Church were to acknowledge it accidentally canonized someone many consider to have been an abusive cult leader, it would not exactly be a good day for the Vatican’s public relations staff.

For now, Opus Dei likely will comply publicly with whatever the pope decrees as a means of pro forma courtesy. But privately, the battle for the hearts and minds of its members will erupt, just as it continues to erupt in other fringe Catholic groups, such as the Society of St. Pius X.

A former member of Opus Dei posed a question and challenge that cuts to the heart of the matter: “It’s time to ask yourself in whom you place the hope of your salvation: Opus Dei or the church? Josemaría or Jesus?”

David Bumgardner is a writer, theologian and educator living in Columbus, Ohio. He is a former BNG Clemons Fellow and a graduate of Texas Baptist College at Southwestern Seminary. He is a licensed commissioned pastor and holds an evangelism license through the Anglican Province of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Diocese of Boga, and Missio Mosaic, an ecumenical missional society and religious order. He is awaiting the conferral of his master of arts in practical theology degree from Winebrenner Theological Seminary. He is currently conducting postgraduate theological research (MTh) at the University of Aberdeen in New Testament and Early Christianity.

Related articles:

Our most basic freedom — deciding one’s own religion | Opinion by Richard Conville

A conservative Baptist’s prayerful appreciation for Pope Francis | Opinion by Benjamin Cole