S. Korea transforms from aid recipient to innovator, powers Missouri’s next-gen science project

University of Missouri Board of Curators Chair Todd Graves speaks during an interview with The Korea Herald at the Dragon City Hotel in Yongsan-gu, Seoul, on Wednesday. (Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald)

University of Missouri Board of Curators Chair Todd Graves speaks during an interview with The Korea Herald at the Dragon City Hotel in Yongsan-gu, Seoul, on Wednesday. (Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald) Leaders from the University of Missouri arrived in Seoul this week to start a new chapter in a partnership that stretches back seven decades — from the aftermath of World War II to the frontiers of modern science.

A delegation representing Missouri’s academic and political leadership — including University of Missouri Board of Curators Chair Todd Graves, UM System President Mun Choi and Missouri House Speaker Jonathan Patterson — sat down with The Korea Herald on Wednesday to discuss their landmark initiative, one that will represent the largest research capital investment in American university history.

Graves, who oversees the university’s governing board, said the project embodies Missouri’s vision to link education, innovation and international collaboration. “This isn’t just about a reactor,” he said. “It’s about positioning Missouri at the center of global science and building partnerships that benefit generations to come.”

Built in collaboration with Hyundai Engineering and the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute or KAERI, the project — the NextGen Missouri University Research Reactor — is a state-of-the-art nuclear research facility designed to produce medical radioisotopes used to diagnose and treat cancer.

Once completed, it is expected to produce a reliable domestic supply of cancer-treating isotopes such as lutetium-177, support cutting-edge radiopharmaceutical development, and train the next generation of scientists and engineers.

“We received proposals from all over the world,” Choi said. “But the best proposal came from South Korea. The Korean technology through KAERI and Hyundai was the most advanced, with a long history of designing and building research reactors around the world.”

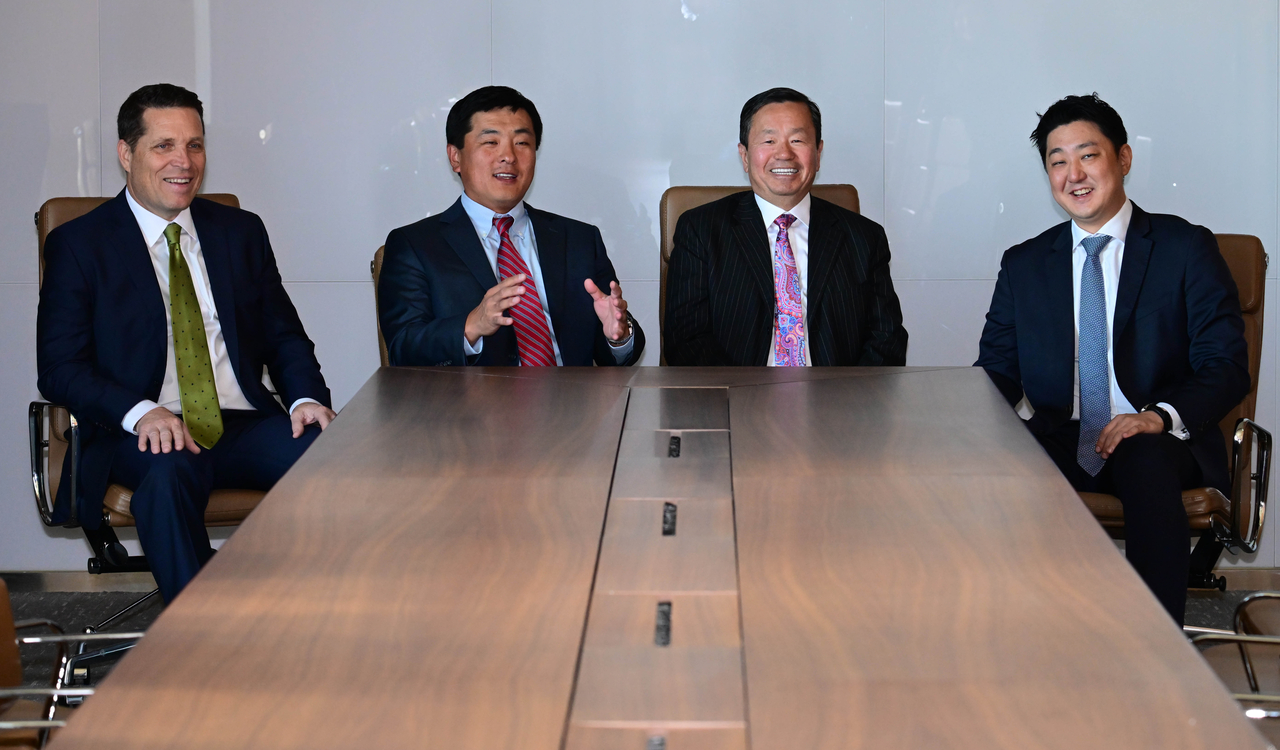

(From left) University of Missouri Board of Curators Chair Todd Graves, Missouri House Speaker Jonathan Patterson, UM System President Mun Choi and Kim Sung-soo, adjunct professor at Yonsei University, speak during an interview with The Korea Herald on Wednesday at Dragon City Hotel in Yongsan-gu, Seoul. (Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald)

(From left) University of Missouri Board of Curators Chair Todd Graves, Missouri House Speaker Jonathan Patterson, UM System President Mun Choi and Kim Sung-soo, adjunct professor at Yonsei University, speak during an interview with The Korea Herald on Wednesday at Dragon City Hotel in Yongsan-gu, Seoul. (Lee Sang-sub/The Korea Herald) The new reactor, estimated to cost $1.3 billion, will expand the university’s production of medical radioisotopes — substances vital for targeted radiotherapy that treat cancers ranging from brain tumors to leukemia. According to Choi, about 460,000 Americans are treated each year using drugs made with isotopes produced at the university.

The project, he emphasized, is more than a scientific milestone. It is a full-circle moment in the shared history of Missouri and Korea.

The ties trace back to President Harry Truman — a Missouri native — whose decision to send US troops in 1950 was crucial to defending South Korea. After the war, Truman sought to provide higher education opportunities for young Koreans at the University of Missouri, believing that knowledge would rebuild the nation.

“For the past 70 years, many Korean technocrats have studied at the University of Missouri and returned to rebuild their country,” Choi said. “Now, we’re benefiting from Korean ingenuity and scientific progress.”

Korea’s nuclear research began in 1959, when the country, with US support, broke ground on its first research reactor, the TRIGA Mark-II.

From those early days of American assistance, Korea has steadily built one of the world’s most advanced nuclear capabilities. In 1995, it achieved full technological self-reliance by independently designing, constructing and operating its first domestic research reactor, Hanaro.

Since then, Korean engineers have exported their expertise across the globe, designing and building research reactors in Jordan, Malaysia, the Netherlands and other countries. Including the Missouri contract, Korea’s total number of research reactor exports now stands at seven.

Officials in both countries say this achievement carries profound meaning. It marks the moment when a nation that once imported a US reactor has, through decades of relentless research and development, “reverse-exported” its technology back to America.

“Educational collaboration isn’t just about degrees,” Graves added. “It’s about perspectives. When students from Korea or any other country join our classrooms, they enrich the discussions and broaden how we see the world.”

For Speaker Patterson, who was adopted from Korea at age six and grew up in Missouri, the trip carried personal resonance. “Back in 1986, I was the only kid who looked different in my class,” he recalled. “Now the world is much more diverse and open. Coming back here feels like completing a circle.”

Following their meetings in Seoul, the group will travel to Daejeon to visit the Korea Atomic Energy Research Institute headquarters and to Busan, home to Korea’s major industrial and engineering hubs, to explore further collaboration opportunities.

Graves said he hopes the partnership will continue to grow in ways that keep Missouri at the heart of global cooperation. “We’re the middle state in the middle of America,” he said. “Our university president was born in Korea. Our House speaker was born in Korea. That symbolizes how far this relationship has come — and how much further it can grow.”

jychoi@heraldcorp.com