In this way, Souq al-Tanabel anticipated the global convenience-food trend by decades.

While frozen meals and pre-packaged salad kits only began filling supermarket shelves in the US and Europe in the late 2000s, Damascene women and traders had already perfected a system that lightened household burdens, saved time and energy, and preserved social bonds. For them, the market was never about laziness — it was about survival, adaptation, and community.

For Dr. Faris Arab, 38, an orthopaedic physiotherapist now living in New Delhi, Souq al-Tanabel is inseparable from the scents and sounds of his childhood. “I used to buy all our groceries there — everything from bread to milk to vegetables,” he tells TRT World.

His fondest memory belongs to the bakery just behind his home. “The smell of fresh chocolate and cheese croissants would rise to our floor. I would rush down like Jerry the mouse,” he laughs, recalling himself as a nine-year-old boy.

Dr Arab, displaced by the war 14-year-old that ended after the Assad regime was toppled in December last year, still carries those memories with him. His family has been scattered, their photographs and belongings lost to fire and the rubble of armed conflict.

“Because of the war, I was deprived of my childhood country, and all my memories are slowly fading away,” he says quietly. What endures are fragments: the smell of bread, the sight of stuffed zucchini, the rhythm of vendors calling out their offers. Arab insists, the market was never about laziness, but served as an economy of care woven into daily life.

Post-war recovery in Syria

After years of conflict, many feared Souq al-Tanabel would fade into silence. Instead, the opposite has happened: its lanes feel more alive than ever. Vendors call out their offers, customers press past one another, and the rapid thud of knives against cutting boards echoes along Shaalan’s narrow streets.

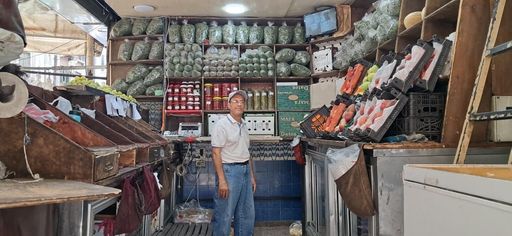

“Before the war, people used to prepare in bulk for the winter,” says Imad Shurba, 47, who has sold vegetables here for nearly 25 years. “Now they buy less, but they come more often. The souq is still alive — maybe even more alive — because everyone depends on it daily.”

For scholars, the vitality of the marketplace speaks to more than commerce. “A place like Souq al-Tanabel can help people reconnect after years of disruption,” Gharipour adds. “It can bring back familiar rhythms — buying bread from the same baker, chatting with neighbours, listening to a storyteller in the corner.” These everyday moments, he says, rebuild trust and a shared sense of belonging.

At one stall, Ummu Hafiz, 60, from the Golan, adjusts her headscarf as she hollows zucchini. Her story is heavier than the sacks of peas stacked beside her. During the war, regime forces targeted her family. “They first took my eldest son while he was sleeping,” she recalls. “Then they came back for my husband.” Two more sons were also taken, another fled abroad — leaving her with six daughters and the daunting task of survival.

“Before, I never worked,” she says. “But when my husband and sons were gone, I had no choice. I came here, started peeling, bagging, and hollowing. It doesn’t bring much, but thanks to God, we never had to beg.” For Hafiz, the souq is not just a workplace but a fragile anchor in a life reshaped by war.

Gharipour notes that markets like Souq al-Tanabel are lifelines for women and small producers. “They don’t require huge investments to get started, so people can sell food or other goods with minimal barriers. That keeps income circulating inside the community. And it’s not just about selling — markets are places to learn new skills, share ideas, and build networks. For women especially, they can be platforms to run businesses, gain independence, and support their families’ and neighbourhoods’ recovery.”

For anthropologist Totah, the change is striking. “Traditionally, women did not usually work inside bazaars. They shopped there, but rarely stood behind the stalls. What we see in Shaalan is a reconfiguration — women becoming vendors themselves, reflecting both modern pressures and the impact of war,” she tells TRT World.

Totah adds that Souq al-Tanabel is more transactional than social in its commerce. “It is good to see more women involved in the souq, but this may not last given Syria’s shifting political and social environment.” Still, she notes, women are drawn to this market more than to traditional bazaars, precisely because it meets the pressing needs of daily life. Here, everything is ready to cook — a relief in households where time is scarce and work never ends.

Among those who keep the souq running today is Um Talal, 68, who has spent the past decade working its stalls. Her day begins at seven in the morning and often stretches until dusk, for her there are no days off. “I work every day out of necessity,” she explains. “From seven in the morning until seven in the evening, then I go home. Most of what we do goes to the shopkeepers, but the hollowed zucchini is mainly for housewives who want to cook quickly.”

Her labour is relentless, but it sustains an extended family. “I take care of my divorced daughter and her two children, my son and his two girls, and two orphaned girls. A whole family, carried together,” she says.

Chronic illness accompanies her shifts. “I have diabetes and high blood pressure, but I keep working. It is tiring, but God provides our sustenance through these stalls.”

For Um Talal and hundreds of others, the souq is both a workplace and a lifeline — a fragile but essential bridge between her family’s survival and the city’s daily rhythm.