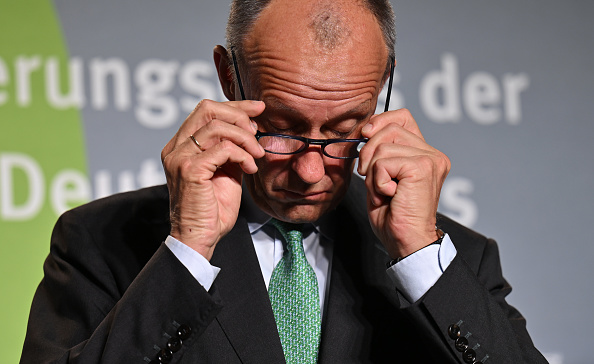

BERLIN – Chancellor Friedrich Merz, battling a surge in support for the far-right AfD ahead of five key state elections in 2026, has come under fire for remarks widely seen as echoing racist tropes about immigrants, sparking one of the biggest controversies of his chancellorship.

Speaking to reporters in Potsdam last week, Merz said that while deportations of rejected asylum seekers had accelerated, “of course, we still have this problem in how our cities look,” using the German word for cityscape or city appearance: Stadtbild.

Several prominent Merz allies – including conservative parliamentary leader Jens Spahn and and commentators including Bild newspaper chief political writer Peter Tiede – sided with the chancellor, saying he had addressed the reality of everyday life in Germany and was referring to drug dealers and young, male illegal immigrants hanging around train stations and city centres, making people feel unsafe.

However, the comment reignited a national debate over migration, integration and racism, with critics accusing Merz of adopting far-right AfD rhetoric to win back conservative voters.

Backlash across the spectrum

The backlash came swiftly. Members of his coalition partners, the Social Democrats (SPD) and the Greens, accused the chancellor of using “divisive language,” while the opposition called the remark unworthy of his office.

Even within his own Christian Democratic Union (CDU), prominent figures voiced unease. Berlin’s CDU mayor Kai Wegner said the capital’s problems with crime and cleanliness “cannot be pinned on nationality,” while former CDU chancellor candidate Armin Laschet called the comment “too nebulous.”

Several dozen Green MPs signed an open letter calling Merz’s words “racist, discriminatory, hurtful and indecent,” urging him to apologise to “all first-, second- and third-generation immigrants who face racism and exclusion every day.”

Germany has around 25 million residents with an immigrant background – about 30% of the population – including 13 million with German citizenship, according to the Federal Agency for Civic Education.

Immigrant groups accused Merz of placing entire communities under suspicion. “He has cast millions of people as outsiders in their own country,” said Ali Can, founder of the VielRespektZentrum intercultural initiative.

Instead of retracting his comment, Merz doubled down. Asked by reporters on Monday whether he regretted his statement, he replied: “Ask your daughters, ask your friends – everyone will confirm this is a problem, at least after dark.” He added: “I have nothing to take back. On the contrary.”

Yet as the outcry continued, Merz changed course late Wednesday and began to aggressively walk his comments.

On the sidelines of a meeting between European officials and Western Balkan leaders in London, Merz read out a prepared statement, saying Germany valued its immigrant communities and that by Stadtbild he meant people without residence permits who did not stick to the rules.

“Many of these also shape the public image of our cities. That is why so many people in Germany and other European Union countries – and this does not only apply to Germany – are now simply afraid to move around in public spaces,” Merz said. This affects train stations, underground stations and certain parks. ‘It shapes entire neighbourhoods, which also cause major problems for our police.’

He added that Germany would continue to need immigration and said migrants were “an indispensable part of our labour market.”

By the end of his statement, Merz appeared to have turned 180 degrees.

“We simply cannot do without them anymore, no matter where they come from, what colour their skin is, and no matter whether they are first, second, third or fourth generation immigrants living and working in Germany.”

Risky strategy against the AfD

Merz is known for shoot-from-the-hip statements, but commentators said his Stadtbild salvo sounded like a calculated “dog whistle” message to woo back AfD voters

The German chancellor’s remarks came shortly after a CDU leadership meeting focused on countering the AfD’s rise ahead of the 2026 elections in Baden-Württemberg, Rhineland-Palatinate, Berlin, Saxony-Anhalt and Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania.

A poll released by the Forsa polling institute this week places the AfD at 26% nationwide, ahead of the CDU at 24%. Meanwhile, in Saxony-Anhalt, the AfD is far ahead at 40% against the CDU’s 26%.

Yet, Merz has ruled out any cooperation with the AfD as the domestic intelligence service classifies as a suspected right-wing extremist party.

“The AfD is questioning all the fundamental decisions the Federal Republic has made since 1949,” he said. “The hand it extends is, in reality, a hand that wants to destroy us.”

However, some CDU officials – particularly in eastern Germany, where the AfD is strongest – have urged a softer line. In Saxony and Thuringia, where the far right won more than 30% in 2024, the CDU was forced into fragile coalitions to keep it out of government. And the possibility of an outright AfD victory in Saxony-Anhalt next year is seen as a serious test for Merz’s leadership.

Analysts warn that the chancellor’s strategy may backfire. “Why should anyone return to the CDU,” asked sociologist Oliver Nachtwey on Deutschlandfunk radio on Tuesday, “if they hear the same message, just delivered in a milder tone?”

The controversy also spilled into the streets. On Tuesday night, thousands gathered outside CDU headquarters in Berlin under the slogan “We’re the daughters,” in response to Merz’s earlier claim that “your daughters” would confirm his remarks about safety in cities.

“We will not be used as an excuse for racist and unacceptable statements,” said environment activist Luisa Neubauer, addressing the crowd.

Political fallout and uncertainty

Merz has been in office for six months but is already struggling to maintain momentum.

His coalition with the Social Democrats has been divided over how to revive the stagnant economy, modernise infrastructure and reform welfare spending.

Economists also warn that Germany’s budget discipline and demographic pressures are straining public finances, while voters increasingly see the government as ineffective, with opinion polls showing that there is already a widespread public perception that the government is too divided to turn the country around.

A far-right party coming to power in a German state for the first time since 1945 would be a stain on Merz’s chancellorship, and trying to sound like the AfD while distancing himself from it is not a winning strategy, critics say.

Instead, Merz would be better advised to “urgently address the problems and concerns of the vast 80% majority of eligible voters who want nothing to do with the AfD”, Manfred Güllner, head of the Forsa polling institute, said in a note on Wednesday.

(cs, mm)