It all started in a library.

In 2023, Colin Mannex, executive director of Kenworthy Performing Arts Center (KPAC) in Moscow, Idaho, was participating in a humanities panel at Washington State University when he first heard about a largely forgotten 1919 film. It was called Told in the Hills — the first feature film shot in Idaho.

Based on Marah Ellis Ryan’s 1891 novel, the Western romance follows Genesee Jack, an Idaho settler seeking a new life, and the estranged brother who travels west to find him. The silent film was shot on location in Lawyer’s Canyon south of Lewiston and featured over 100 Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) actors.

Mannex, whose interest in the silent film era had already inspired KPAC’s annual Silent Film Festival, couldn’t wait to see it. So he was delighted to learn that two delicate reels of film —along with the original shooting script and hundreds of still photos from the production — were tucked away in the Idaho Film Collection in the library at Boise State University archives.

Production of the film in Lawyer’s Canyon south of Lewiston, Idaho. Credit: Boise State University Idaho Film Collection

Production of the film in Lawyer’s Canyon south of Lewiston, Idaho. Credit: Boise State University Idaho Film Collection

It turned out that Mannex wasn’t the first person to become interested in the film. There in the archives, Mannex encountered an eccentric poet and English professor named Tom Trusky, whose short 1989 documentary, Retold in the Hills, chronicled his journey to the Gosfilmofond State Film Archive in what was then the Soviet Union to retrieve the original nitrate spools of Told in the Hills, followed by his efforts to preserve them.

Mannex caught Trusky’s “electric energy and excitement” and picked up where he left off.

Through KPAC, he applied for a $7,500 grant from the Idaho Humanities Council (IHC) in January 2024. The council awarded funding for the restoration, and Mannex commissioned a new score from award-winning Diné composer Connor Chee. He found a company to handle a 4K restoration of the fragile film and hired an editor to help piece together the narrative. Mannex connected with the Nez Perce to find out what the tribe knew about the film’s creation and to consult with them about its restoration. More funds were raised, and finally, a premiere was set for September 2025.

But then Idaho got DOGE’d.

The bad news came in April, in the middle of the night: an email from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH). It said “that our grant was terminated,” Camille Daw, program officer at IHC, told High Country News. The decision had been made by DOGE — the Department of Government Efficiency founded by billionaire Elon Musk and given free rein by the Trump administration to indiscriminately slash the budgets of federal agencies and fire their employees.

“It was a big surprise for our office,” Daw said.

Each year, the Idaho Humanities Council disburses the funds it receives from NEH across Idaho. But two days after DOGE focused its eye on the humanities, 70% of IHC’s funding was gone.

The cuts ripped through Idaho, and the council scrambled to downsize or delay the grants it had already promised, including the one to KPAC. The film’s planned premiere was only months away.

“It just totally derailed everything,” Mannex said.

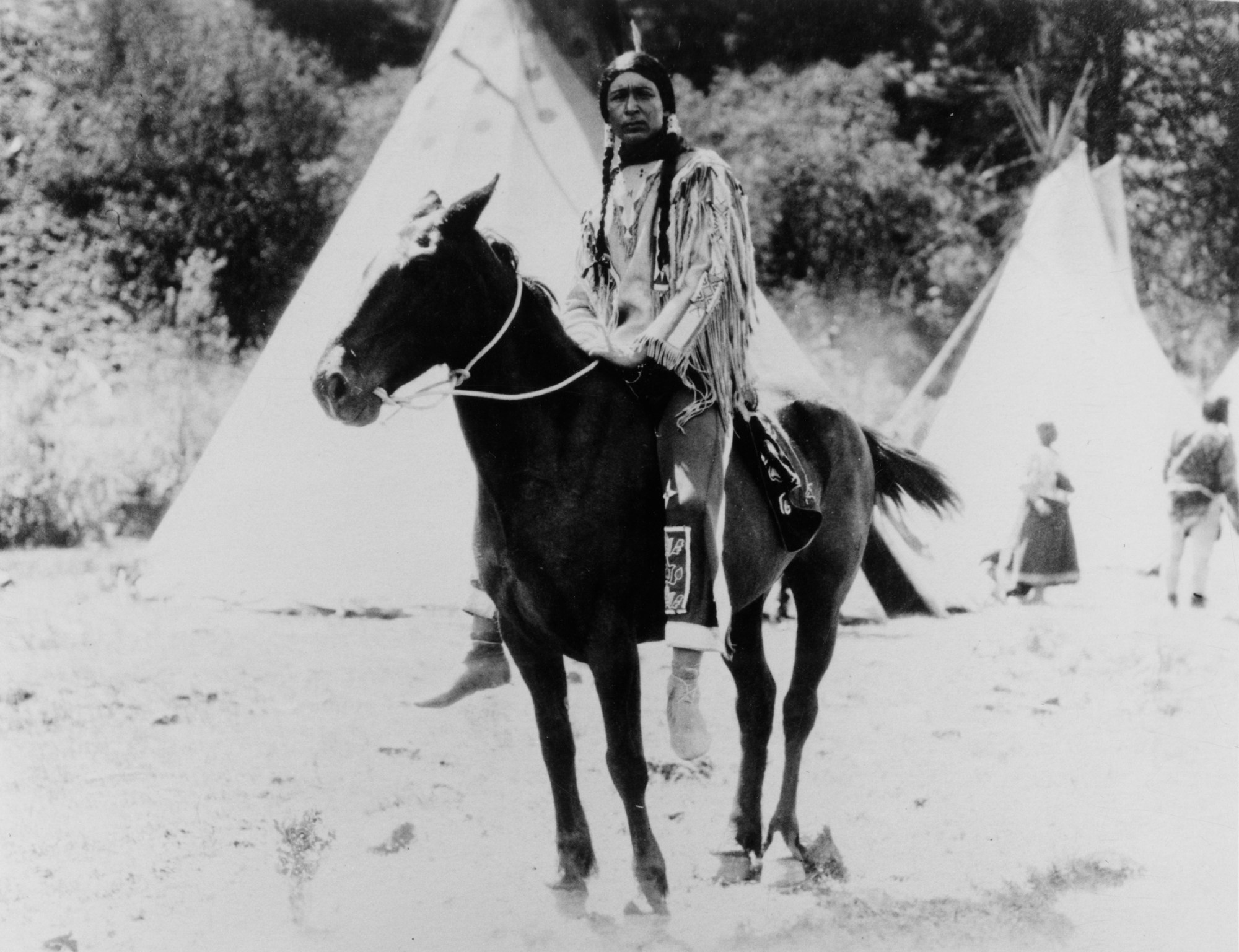

The silent film featured over 100 Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) actors. Credit: Boise State University Idaho Film Collection

The silent film featured over 100 Nimiipuu (Nez Perce) actors. Credit: Boise State University Idaho Film Collection

OVER A HUNDRED YEARS before DOGE existed, Nimiipuu people were adapting to federal threats of their own at the same time that Told in the Hills was being filmed. By 1919, federal boarding schools were removing Indigenous children from their families, government policies were dispossessing tribes from their land and threatening their way of life. An entire generation of Nimiipuu people had grown up under government bans on their traditions.

“Many of those individuals (in the film) were in armed conflict with the U.S. federal government in the 1877 (Nez Perce) War,” said Nakia Williamson-Cloud, Nez Perce Cultural Resource Program director and a consulting partner on the film restoration project. “When you look into the faces of those individuals on film and in the photographs, you know that they faced challenges to their very existence.”

In this way, Told in the Hills is an artifact that vividly preserves the resistance of the Nez Perce people to that attempted erasure.

Williamson-Cloud put the DOGE fiasco into perspective. “Nez Perce people have been on this landscape in excess of 16,500 years. We’ve seen a lot of changes. Our memory is not only ancestral over generations, our memory is on par with geological events that we observed on the landscape,” he said.

“This federal government has only been here just a speck amount of time. Tiny amount of time. And that’s what we’re here to remind the broader society,” he said, “is just the resilience of our people.”

THE TOLD IN THE HILLS restoration team was unwilling to cave to DOGE.

“After the funding cuts,” composer Connor Chee said, “things got scaled back.” The full chamber orchestra he and Mannex had originally envisioned shrank to a quintet.

“I didn’t get to see the finished film,” Chee said. “And I had to get this music to the performers in time for them to rehearse it and learn it.”

In the end, the conductor and musicians had two weeks to practice. Editing was paused until funding could be restored. Chee created flexible musical cues that could expand to match the unfinished final cut of the film.

“I don’t know how it’s going to sound. It could be different every time it’s performed,” Chee said. “This kind of music can stay alive, it can change. It’s like a living thing.”

As the team worked on the film’s restoration, they compared the new scan with the tape Trusky produced in the 1980s. In one shot, the Trusky-era footage shows two actors, their faces obscured in deep shadows.

In the restored 4K version of that scene, however, their faces emerge in sharp relief. By examining the new version of the film and the collection of still photos, Williamson-Cloud and his team at the Cultural Resources Office were able to finally credit dozens of previously unrecognized Indigenous actors.

Mannex and editor Tom Frank also had to “complete” the film, which they did by consulting the original shooting script, then incorporating the trove of stills into the surviving third of the restored film.

“We have essentially 20 minutes of footage for a 60-minute film,” Frank said. “We ultimately realized that using just one or two photos to represent the scene with text from the script was the way to make it most clear.”

All the while, Mannex scrambled. The contracts for editing and score composition were reliant on the slippery missing funding. In the crucial final months, the Mellon Foundation stepped up. Local donors pitched in to KPAC. Then a court reversal of DOGE’s decision restored the original funding.

It had been a summer of confusion and uncertainty. And with less than a week to go, the film was ready.

Nakia Williamson-Cloud, Nez Perce director of cultural resources; Colin Mannex, KPAC executive director; Tom Frank, film editor; Gwyn Hervochon, BSU librarian and archivist; and Alessandro Meregaglia BSU librarian and archivist, under the marquee the night of the film showing. Credit: Courtesy of Lauren Paterson

Nakia Williamson-Cloud, Nez Perce director of cultural resources; Colin Mannex, KPAC executive director; Tom Frank, film editor; Gwyn Hervochon, BSU librarian and archivist; and Alessandro Meregaglia BSU librarian and archivist, under the marquee the night of the film showing. Credit: Courtesy of Lauren Paterson

For the first time in over 100 years, “Told in the Hills” is played to an audience. Credit: Courtesy of Tom Frank

For the first time in over 100 years, “Told in the Hills” is played to an audience. Credit: Courtesy of Tom Frank

ON A CHILLY FRIDAY NIGHT in September, conductor Danh Pham and the musicians waited at the base of the stage inside the Kenworthy. The theater began to fill. Silent digital projection had replaced the clicking of unspooling film, but the cursive title lit up the screen in silver all the same.

For the first time in over 100 years, Told in the Hills had an audience. But Mannex wanted to prepare viewers for what they were about to see. “You’ll see some old tropes and casting decisions that are uncomfortable for contemporary audiences,” he said, standing by the musicians. “Despite its flaws, Told in the Hills remains an important cultural resource.”

Indeed, the portrayal of and language used to refer to Native characters, as well as the minstrelesque presentation of the film’s Black characters, earned groans from the audience.

“Context is everything,” Williamson-Cloud said of the film’s racist tropes and language. “It’s an important discussion for the time we live in now. We have to take these things head-on and shed light on the ignorance that drives this sort of language.”

The film is a product of its time, and so it features white actors in greasepaint alongside Cherokee actor Monte Blue, a future star who played supporting lead Kalitan, and Joe Kentuck, a Nez Perce performer who played Kalitan’s father. But the film also challenges the era’s cultural stereotypes by presenting peaceful relations between Native Americans and early settlers. The film’s battle scene, a section that had been lost, occurs only because of a misunderstanding: the fault of an American cavalry unit.

Colin Mannex, Tom Frank, Nakia Williamson-Cloud, Alessandro Meregaglia and Gwyn Hervochon during the panel discussion following the film. Credit: Courtesy of Conner Jackson

Colin Mannex, Tom Frank, Nakia Williamson-Cloud, Alessandro Meregaglia and Gwyn Hervochon during the panel discussion following the film. Credit: Courtesy of Conner Jackson

Though the hundreds of Nimiipuu extras stood in for a different tribe (the story focuses on the Kootenai people), they nonetheless seized the rare opportunity to present their actual traditions to an audience. The Native actors were neither costumed nor directed, and appear in their own clothing, enacting their own traditional dances and other ceremonies.

Over a century later, Told in the Hills is being reimagined. And it’s still a work in progress. Mannex told High Country News he wishes the film’s ending had survived. “It would be really cool to see that,” he said. Those final scenes prominently featured Nimiipuu actors and, presumably, remain lost.

“We started out intending full fidelity to the script, but I think there’s more artistic license we can exercise going forward,” he said. He hopes to build on the collaborative relationship with the Nez Perce Tribe, creating a product that combines the culturally significant production images with audio commentary. The film will be released on DVD and probably screened again, but it also may be reinterpreted, presented in another form, like a museum exhibit.

Williamson-Cloud shared the hope that Told In the Hills can remain “a living document for us to add to,” and that the survival of Nimiipuu people against attempted erasure is the restored film’s ultimate takeaway. “Our existence today is sometimes seen as an inconvenient fact,” he said. “But this (version of the film) is a starting point to revisit this time and place while looking to the future.”

The Native actors were neither costumed nor directed, and appear in their own clothing. Credit: Boise State University Idaho Film Collection

The Native actors were neither costumed nor directed, and appear in their own clothing. Credit: Boise State University Idaho Film Collection

Spread the word. News organizations can pick-up quality news, essays and feature stories for free.