Alberta invoked the notwithstanding clause on Monday as it introduced legislation to force striking teachers back to work.

Here’s a quick primer on the rarely-used mechanism, and why it matters.

What is the notwithstanding clause?

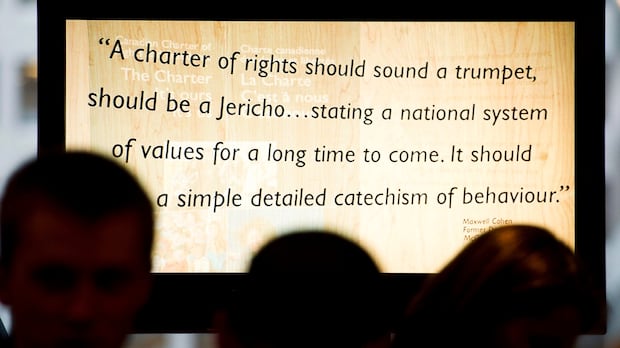

The notwithstanding clause refers to Section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

Essentially, it allows a federal or provincial legislature to pass legislation that violates certain constitutional rights and freedoms, “notwithstanding” the protection of those rights in the Charter.

Which rights are affected?

Section 33 can only be used to override sections 2, and 7–15. Those cover the “fundamental,” “legal” and “equality” rights.

Those sections include some of the Charter’s key principles, such as the:

freedom of expressionfreedom of religionfreedom of associationprotection against unreasonable search and seizureright to legal counsel and habeas corpusprotection against cruel and unusual punishmentprotection from discrimination by the government

The notwithstanding clause cannot be applied to democratic rights, mobility rights, language rights or the sexual equality clause.

The clause expires five years after being invoked. Since elections must be held at least every five years, the public has an opportunity to hold the government that invoked it to account.

Why does it exist?

When Canada repatriated its constitution from the United Kingdom in 1982, provincial governments were hesitant to agree to the new Charter of Rights and Freedoms, fearing a shift of power from legislatures to the judiciary.

The notwithstanding clause was a compromise suggested by Peter Lougheed — Alberta’s premier at the time — to make the Charter more palatable to the provinces and convince them to agree to it.

How often has it been used?

Since 1982, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Yukon have all passed laws invoking the notwithstanding clause.

Some recent examples:

Alberta used it in 2000 to pass anti-same-sex marriage legislation.Quebec used it in 2019 to prevent the wearing of religious symbols by public employees in positions of authority; the legislation (including the notwithstanding clause) was renewed for another five years in 2024.Saskatchewan used it in 2023 for legislation regarding sexual education and requiring parental notification when students change their name or pronouns.Does the Charter provide a right to strike?

In 1987, a reference opinion by the Supreme Court regarding an Alberta law restricting the right to strike stated that “freedom of association” was an individual right — in other words, there was no constitutional right to strike.

That was overruled by a landmark Supreme Court decision in 2015, which established that the Charter does in fact protect a right to strike.

“The right of employees to strike is vital to protecting the meaningful process of collective bargaining,” Justice Rosalie Abella wrote in the decision, Saskatchewan Federation of Labour vs. Saskatchewan.

Barry Eidlin, a professor of sociology at McGill University, says the case was a game changer for workers’ rights in Canada.

“Prior to that ruling in 2015, legislatures could and did frequently pass back-to-work legislation,” he says.

“Indeed, Canada sort of stood apart from the rest of the world in its propensity to legislate workers back to work.”

What if workers ignore a back-to-work law?

The consequences would depend on the specifics of the law and how it is enforced. But Eidlin points to a case in 2022 as instructive.

That year, Ontario Premier Doug Ford invoked the notwithstanding clause to pass legislation preventing education workers from striking.

The backlash was swift. Polling showed only 36 per cent of Ontarians supported the move. The education workers went on strike anyway, and unions across the province threatened a general strike.

Four days later, Ford backed down. The legislation was quickly repealed and the education workers agreed to end their strike and return to bargaining.

“What it emphasizes is that government action is ultimately founded on its ability to be perceived as a legitimate political actor,” says Eidlin. “And in cases where government acts in ways that are perceived as illegitimate, it is highly likely that their actions will be disobeyed.”