What about the BRICS

BRICS

The term BRICS (an acronym for Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) was first used in 2001 by Jim O’Neill, then an economist at Goldman Sachs. The strong economic growth of these countries, combined with their important geopolitical position (these 5 countries bring together almost half the world’s population on 4 continents and almost a quarter of the world’s GDP) make the BRICS major players in international economic and financial activities.

Common Monetary Fund? Has it become operational?

This Fund, known as the CRA (Contingent Reserve Arrangement) and created in 2014 [1] to fulfil a role typically performed by the IMF

IMF

International Monetary Fund

Along with the World Bank, the IMF was founded on the day the Bretton Woods Agreements were signed. Its first mission was to support the new system of standard exchange rates.

When the Bretton Wood fixed rates system came to an end in 1971, the main function of the IMF became that of being both policeman and fireman for global capital: it acts as policeman when it enforces its Structural Adjustment Policies and as fireman when it steps in to help out governments in risk of defaulting on debt repayments.

As for the World Bank, a weighted voting system operates: depending on the amount paid as contribution by each member state. 85% of the votes is required to modify the IMF Charter (which means that the USA with 17,68% % of the votes has a de facto veto on any change).

The institution is dominated by five countries: the United States (16,74%), Japan (6,23%), Germany (5,81%), France (4,29%) and the UK (4,29%).

The other 183 member countries are divided into groups led by one country. The most important one (6,57% of the votes) is led by Belgium. The least important group of countries (1,55% of the votes) is led by Gabon and brings together African countries.

http://imf.org

when a member country experiences a shortage of foreign exchange reserves and requires a loan. The CRA aimed to assist BRICS member nations facing difficulties in securing foreign currency for their international payments, allowing them to draw from this fund to cover their currency shortfalls. This arrangement could potentially enable BRICS countries to bypass the conditions imposed by the IMF.

This fund holds significant importance for South Africa, a founding member, as well as for other more vulnerable BRICS+ nations, including Ethiopia and Egypt, which joined BRICS+ in 2024. These countries frequently encounter shortages of foreign currency, which compels them to seek assistance from the IMF.

However, the CRA’s founding statutes include a condition stipulating that any BRICS member country requesting assistance must adhere to IMF conditions if it seeks to access more than 30% of the total amount to which it is entitled. For example, this principle permits South Africa to borrow up to $10 billion. Should South Africa wish to borrow in excess of $3 billion from the BRICS Monetary Fund, it must demonstrate that it is implementing an IMF programme and complying with the conditions set forth by the IMF. Article 5 of the treaty establishing the BRICS Monetary Fund clearly articulates this principle. [2]

Despite its formal creation in 2014, this fund remains non-operational.

A glaring example of a missed opportunity for the BRICS Monetary Fund occurred with South Africa in mid-2020, when, instead of turning to the BRICS, Pretoria’s finance minister secured a US$4.3 billion loan from the IMF. This resulted in extreme austerity, which caused deep popular discontent with the ANC government before the president softened the finance minister’s social austerity policy.

The BRICS summit that ended on 7 July 2025 produced an evasive statement about the CRA. In point 53 [3] , the BRICS+ leaders state that the founding treaty will be revised and that new members will be able to join the BRICS Monetary Fund. However, this statement lacks concrete details.

This evidence shows that the CRA is, unfortunately, still mythical and inoperative.

Conclusion: Those asserting that the Rio summit marks a significant advancement for the BRICS Common Monetary Fund are making unfounded claims.

What about the New Development Bank?

In point 45 of the final communiqué of the Rio summit in early July 2025, the BRICS leaders stated the following about the New Development Bank (NDB), created in 2014: ’As the New Development Bank is set to embark on its second golden decade of high-quality development, we recognize and support its growing role as a robust and strategic agent of development and modernization in the Global South.’ [4]. They also stated that they were reappointing Dilma Rousseff, former president of Brazil from 2011 to 2016, to the position of president of the New Development Bank (NDB), which she has held since 2023.

The New Development Bank (NDB)

The NDB was officially established on 15 July 2014 at the 6th BRICS Summit held in Fortaleza, Brazil. The NDB, which is headquartered in Shanghai, granted its first loans at the end of 2016. The five founding countries each have an equal share

Share

A unit of ownership interest in a corporation or financial asset, representing one part of the total capital stock. Its owner (a shareholder) is entitled to receive an equal distribution of any profits distributed (a dividend) and to attend shareholder meetings.

in the Bank’s capital, and none has veto power. In addition to the five founding countries, NDB’s members include Bangladesh, the United Arab Emirates, Egypt and Algeria. The capital of the NDB currently stands at $50 billion, with plans to grow to $100 billion in the future. The New Development Bank has declared its primary focus on financing infrastructure projects, such as water distribution systems and renewable energy production systems. It emphasizes the ’green’ nature of the projects it finances, although this assertion is disputed by some authors such as Patrick Bond

Bond

A bond is a stake in a debt issued by a company or governmental body. The holder of the bond, the creditor, is entitled to interest and reimbursement of the principal. If the company is listed, the holder can also sell the bond on a stock-exchange.

(see ’BRICS New Development Bank Corruption in South Africa’, 5 September 2021).

BRICS leaders have announced their support for the NDB’s local currency financing; however, they do not acknowledge that the majority of the NDB’s financing is conducted in dollars through securities issued on financial markets. The NDB primarily borrows and lends in dollars. In 2023 and 2024, the NDB issued bonds that received AA+ ratings (stable outlook) from Fitch Ratings and AA ratings (stable outlook) from S&P Global Ratings. To maintain these rating levels, the NDB effectively complies with the sanctions imposed on Russia following the invasion of Ukraine at the end of February 2022, which has resulted in the NDB not granting any credit to Russia since 2021. The management of the NDB believes that continued lending to Russia could lead rating agencies

Rating agency

Rating agencies

Rating agencies, or credit-rating agencies, evaluate creditworthiness. This includes the creditworthiness of corporations, nonprofit organizations and governments, as well as ‘securitized assets’ – which are assets that are bundled together and sold, to investors, as security. Rating agencies assign a letter grade to each bond, which represents an opinion as to the likelihood that the organization will be able to repay both the principal and interest as they become due. Ratings are made on a descending scale: AAA is the highest, then AA, A, BBB, BB, B, etc. A rating of BB or below is considered a ‘junk bond’ because it is likely to default. Many factors go into the assignment of ratings, including the profitability of the organization and its total indebtedness. The three largest credit rating agencies are Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch Ratings (FT).

Moody’s : https://www.fitchratings.com/

and investment funds

Investment fund

Investment funds

Private equity investment funds (sometimes called ’mutual funds’ seek to invest in companies according to certain criteria; of which they most often are specialized: capital-risk, capital development funds, leveraged buy-out (LBO), which reflect the different levels of the company’s maturity.

to perceive the NDB as taking on significant risks, consequently resulting in higher returns being demanded for purchasing its bonds in international markets.

The NDB’s compliance with sanctions, resulting in the cessation of new loans to Russia, is clearly outlined on the NDB website: https://www.ndb.int/projects/all-projects/. Since the beginning of 2022, the NDB has approved the financing of more than 50 different projects, none of which are located in Russia. With regard to loans to Russia, if you click here: https://www.ndb.int/projects/all-projects/?country=russia&key_area_focus=&project_status=&type_category=&pyearval=#paginated-list, you can find that the last project financially supported by the NDB in Russia dates back to September 2021. In the report presented to investors by NDB President Dilma Rousseff, it is clearly stated that the Bank has frozen lending to Russia since 2022; see page 35 of https://www.ndb.int/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Investor-Presentation-April-2025_FINAL.pdf.

Here we present an extract from a highly critical statement about the NDB made in October 2023 at the Valdai Club, which is very close to Putin, by Paulo Nogueira Batista. Paulo Nogueira is Brazilian and was vice-president of the NDB. Although he is a staunch supporter of the BRICS, he stated:

“Why can we say that the NDB has been a disappointment so far? Here are some of the reasons. Disbursements have been surprisingly slow, projects are approved but not turned into contracts. When contracts are signed, the actual implementation of projects is slow. The results on the ground are meagre. Operations – financing and loans – are mainly conducted in US dollars, which is also the Bank’s unit of account.

How can we, as BRICS, credibly talk about de-dollarisation if our main financial initiative remains predominantly dollarised?

In comparison to other categories of public lenders, how significant are the loans granted by the BRICS Bank?

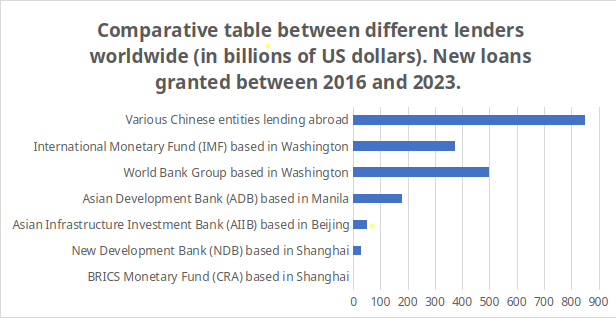

Comparative table between different lenders worldwide (in US dollars). New loans granted between 2016 and 2023.

BRICS Monetary Fund (CRA) based in Shanghai

No loans/No activity

New Development Bank (NDB) based in Shanghai

30 billion

Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) based in Beijing

50 billion

Asian Development Bank (ADB) based in Manila

180 billion

It consists of several closely associated institutions, among which :

1. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, 189 members in 2017), which provides loans in productive sectors such as farming or energy ;

2. The International Development Association (IDA, 159 members in 1997), which provides less advanced countries with long-term loans (35-40 years) at very low interest (1%) ;

3. The International Finance Corporation (IFC), which provides both loan and equity finance for business ventures in developing countries.

As Third World Debt gets worse, the World Bank (along with the IMF) tends to adopt a macro-economic perspective. For instance, it enforces adjustment policies that are intended to balance heavily indebted countries’ payments. The World Bank advises those countries that have to undergo the IMF’s therapy on such matters as how to reduce budget deficits, round up savings, enduce foreign investors to settle within their borders, or free prices and exchange rates.

Group based in Washington

500 billion

International Monetary Fund (IMF) based in Washington

Between 350 and 400 billion

Various Chinese entities [6] lending abroad

Between 700 and 1,050 billion

Author’s calculations based on information from the websites of the institutions concerned

To compile this table, the author used the period from 2016 to 2023, as the NDB and the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) only began granting loans in 2016. The comparison between the amounts lent indicates the importance of the various lenders. Commentators who claim that the BRICS have set up instruments such as the Monetary Fund (CRA) and the New Development Bank, which are making significant progress and challenging institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, are giving a false picture of reality. Of the two financial institutions created by the BRICS, one, the CRA, has not yet become operational despite having been created more than 10 years ago, and the other, the NDB, has only granted loans for a small amount compared to other public lenders. The NDB’s loans are six times lower than the Asian Development Bank’s, which has strong ties to the World Bank and the IMF. The difference is even greater if we only consider loans to Asia. As for China, it favours its own instruments for granting loans, even though it is a member of the NDB and the latter’s headquarters (like those of the BRICS Monetary Fund) are located on its territory. Through its public banks, China has lent 20 to 30 times more than the NDB. In addition, China has placed greater emphasis on the development of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), in which it is the majority shareholder with 30% of the capital and holds 26.5% of the votes (see https://www.aiib.org/en/about-aiib/governance/members-of-bank/index.html).

Who claim that the BRICS have set up instruments such as the Monetary Fund (CRA) and the New Development Bank, which are making significant progress and challenging institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, are giving a false picture of reality

Let us recall this observation made by Paulo Nogueira in October 2023, which remains valid:

“Let me assure you that when we started with the CRA and the New Development Bank, there was considerable concern in Washington, at the IMF and the World Bank, about what the BRICS were doing in this area. I can attest to this because I was there at the time, serving as an executive director for Brazil and other countries on the IMF Executive Board.

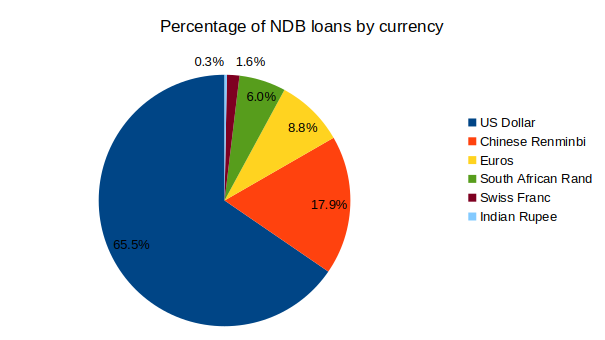

What percentage of loans granted by the BRICS Bank are in US dollars?

Source: NDB, Investor Presentation, April 2025

According to the report presented by the NDB President to investors in April 2025, 65.5% of loans were granted in US dollars, 8.8% in euros and 1.6% in Swiss francs. This gives a total of 75.9% of the loans granted in the currencies of the Western capitalist powers: the United States, the Eurozone and Switzerland. In contrast, only 17.9% were granted in Chinese currency (and this statistic actually concerns loans granted in China by the NDB), 0.3% in Indian currency (in India) and 6% in South African currency to entities in South Africa. For further details, see page 17 of the presentation given to investors in April 2025 : https://www.ndb.int/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Investor-Presentation-April-2025_FINAL.pdf This data indicates that nearly all loans issued by the NDB in India are denominated in US dollars. Similarly, the majority of loans provided in Africa are also in US dollars, while every loan granted in Russia is in US dollars, and all loans issued in Brazil are likewise in US dollars.

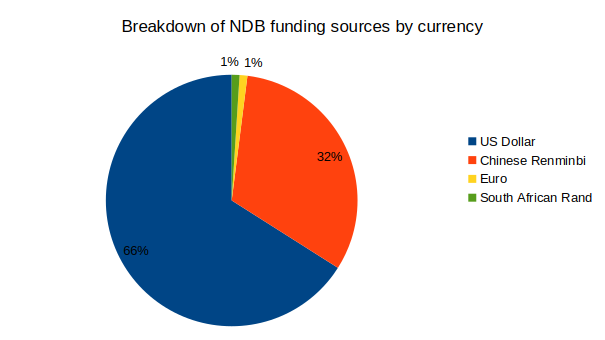

66% of NDB borrowings are in US dollars. Is this evidence of the BRICS New Development Bank’s ongoing de-dollarisation?

The answer is no. The NDB is not becoming independent from financial markets and the dollar, despite some claims. 66% of its outstanding borrowings are in US dollars and 1% in euros and they are bonds sold on financial markets.

Only 32% of its outstanding loans are in Chinese currency, 1% are in South African currency; and 0% are in Russian, Brazilian or Indian currency. See the slideshow presented to investors in April 2025, p. 21 of https://www.ndb.int/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Investor-Presentation-April-2025_FINAL.pdf If the NDB really wanted to, it could finance itself mainly in the currencies of its members and could do without financing itself on the financial markets. Even if part of the loans were granted in dollars, China, Russia, India and Brazil have large dollar foreign exchange reserves that could be used.

Source: NDB, Investor Presentation, April 2025

Source: NDB, Investor Presentation, April 2025

Are the New Development Bank and the BRICS Monetary Fund (CRA) an alternative to the Bretton Woods institutions, as some claim? {{}}

The answer is no, for several reasons.

Firstly, the BRICS countries themselves do not present the New Development Bank and the Monetary Fund (CRA) as an alternative. On the contrary, they affirm that the IMF and the World Bank must remain at the heart of the global financial system. The BRIC+ countries consider that the IMF must remain at the center of the international financial system.

In the final declaration of the BRICS+ summit held in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) in early July 2025, they write in point 11:

They also express their support for the World Bank. In point 12 of their declaration, they state that they want to increase the legitimacy of this institution. However, since their foundation, the World Bank and the IMF have pursued policies that run counter to the interests of people and ecological balance.

In the final declaration, the BRICS countries express no criticism of the neoliberal policies that the two Bretton Woods institutions are actively promoting. At no point do they question the debts that these institutions are demanding from indebted countries.

Secondly, in its 10 years of existence, the BRICS Monetary Fund (CRA) has not granted any loans.

Thirdly, when granting loans, China favours the tools at its direct disposal, i.e., its public banks. Since 2015, Chinese banks have granted 20 to 30 times more loans than the New Development Bank (see table above).

Fourthly, the Chinese authorities have created another multinational bank, separate from the NDB, which a significant number of countries have joined. This is the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), which is based in Beijing. The AIIB has more than 100 member countries (including 23 European countries such as Germany, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Belgium, etc.). The United States and Japan are not members. The AIIB began operations in 2016, at almost the same time as the NDB. The AIIB’s capital amounts to $100 billion, of which approximately 30% is subscribed by China, which is the main shareholder. The voting process is similar to that of the World Bank and the IMF: it is based on the share of capital held, which gives China a de facto veto over major decisions. In conclusion, the AIIB plays a much more important role than the New Development Bank, both in terms of the number of member countries and the volume of loans it grants.

Fifthly, China, which has become the world’s largest public lender and creditor, insists that countries comply with both the IMF and the World Bank and therefore requires debtors to apply the conditions contained in the loan agreements they have signed with these institutions.

On China as a major lender, read : Questions & answers on China as a major creditor power

None of the 50 countries south of the Sahara has had access to credit from the New Development Bank, apart from South Africa

Sixthly, it should be noted that the only loans granted by the NDB in sub-Saharan Africa have been to South Africa. No other country south of the Sahara has had access to NDB credit. And in North Africa, only Egypt has received funding making this loan the sole credit granted to the entire region. In Asia, loans have been issued only to China, Bangladesh, and India. In Latin America, Brazil stands as the only recipient of NDB loans; no other country has received any.

This raises the question: how can we assert that the NDB serves as an alternative to the World Bank and the IMF when, to date, not a single one of the 26 low-income countries has received a loan from the NDB? Among the 51 lower-middle-income countries, only Bangladesh and Egypt have had access to an NDB loan? Bangladesh has received five loans, totalling just under $1 billion (see https://www.ndb.int/projects/all-projects/?country=bangladesh&key_area_focus=&project_status=&type_category=&pyearval=#paginated-list). Egypt received a single loan for $200 million. This number means that the loans granted to these two countries represent less than 4% of the total amount lent by the NDB. The rest of the loans were granted to Russia (until 2021, as loans were stopped from 2022 onwards), Brazil, China and South Africa.

How can we assert that the NDB serves as an alternative to the World Bank and the IMF when, to date, not a single one of the 26 low-income countries has received a loan from the NDB?

Strategic and political summary and conclusion

It should be remembered that the five founding members of BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) could, if they wanted to, form a powerful bloc because they represent 40% of the global population, around 30% of world’s GDP

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

Gross Domestic Product is an aggregate measure of total production within a given territory equal to the sum of the gross values added. The measure is notoriously incomplete; for example it does not take into account any activity that does not enter into a commercial exchange. The GDP takes into account both the production of goods and the production of services. Economic growth is defined as the variation of the GDP from one period to another.

, 20% of international exports, and 20% of global oil production. With the inclusion of the five new BRICS members – Indonesia, Iran, Ethiopia, Egypt and the United Arab Emirates – BRICS+ accounts for around 55% of the world’s population, 45% of global GDP (in terms of purchasing power parity), 25% of worldwide exports and 40-45% of global oil production. However, it must be noted that the BRICS or BRICS+ countries do not form a coherent bloc; they constitute a heterogeneous alliance whose members negotiate separately with the United States.

Ten years after their creation, the New Development Bank and the BRICS Monetary Fund (CRA) are not credible alternatives to the Bretton Woods institutions but rather their peripheral extensions. Behind the rhetoric of ’de-dollarisation’ and financial emancipation of the global South, these two instruments remain trapped in a logic of dependence on international financial markets and implicit submission to IMF discipline. The CRA, which has been inactive since 2014, symbolises this impasse: designed to protect BRICS members from IMF conditionalities, it instead refers them back to the IMF as soon as they exceed a certain borrowing threshold. The NDB, for its part, has become a semi-Westernised institution: most of its financing is denominated in dollars, its ratings depend on the major Anglo-Saxon agencies, and its lending strategy does not aim to provide credit to the countries that need it most. It should be supported in a human development strategy compatible with the balance

Balance

End of year statement of a company’s assets (what the company possesses) and liabilities (what it owes). In other words, the assets provide information about how the funds collected by the company have been used; and the liabilities, about the origins of those funds.

of nature.

Beijing’s attitude is indicative of this ambiguity. In practice, China favours its own state-owned banks, and the AIIB to extend its influence, relegating the NDB to the background. This choice reflects a hierarchy among the financial instruments

Financial instruments

Financial instruments include financial securities and financial contracts.

of the South, where multilateral cooperation remains subordinate to national power dynamics.

Politically, the BRICS+ countries are not breaking with the global financial order. By reaffirming the central role of the IMF and the World Bank in the Rio Summit Declaration (2025), they position themselves as internal reformers of the system rather than architects of an alternative. This stance reveals the founding paradox of the BRICS: wanting to embody the voice of the South without breaking with the structures of domination of the North.

Thus, ten years after the creation of the NDB and CRA in Fortaleza, the promise of a post-Western financial hub remains unfulfilled. Without a shared political will for systemic transformation, the BRICS are solidifying a hybrid model in which the rhetoric of sovereignty conceals ongoing dependencies dependencies. The genuine alternative to the Bretton Woods institutions will not emerge from a mere institutional framework but from a collective initiative centred on financial justice, South-South solidarity and the development of new, truly democratic multilateral financial institutions that prioritise the fulfilment of fundamental human rights and respect for Nature.

The author would like to thank Patrick Bond, Sushovan Dhar and Maxime Perriot for their proofreading and advice. The author is solely responsible for the opinions expressed in this text and any errors it may contain.