Those who follow politics rely more than they like to admit on the information supplied by faces: the curled lip of Putin, the orange mask of Trump, Starmer’s troubled frown. Framed by a screen, frozen in a photograph, they transmit impressions of nation and culture as much as they do individual personality. But in the game of supplying memorable faces, Japan has been a disappointment.

A few people will remember the lavishly coiffured Junichiro Koizumi, who led the country in the early 2000s. Some will recognise the face of Shinzo Abe, Japan’s longest-serving prime minister, who was assassinated after leaving office. But who now recalls anything about Fumio Kishida or Shigeru Ishiba, let alone Naoto Kan or Yoshihiko Noda? During the first quarter of the 21st century Japan has worked its way through a dozen prime ministers; in the mind’s eye they fuse into a single indistinct image of grey, unsmiling solemnity.

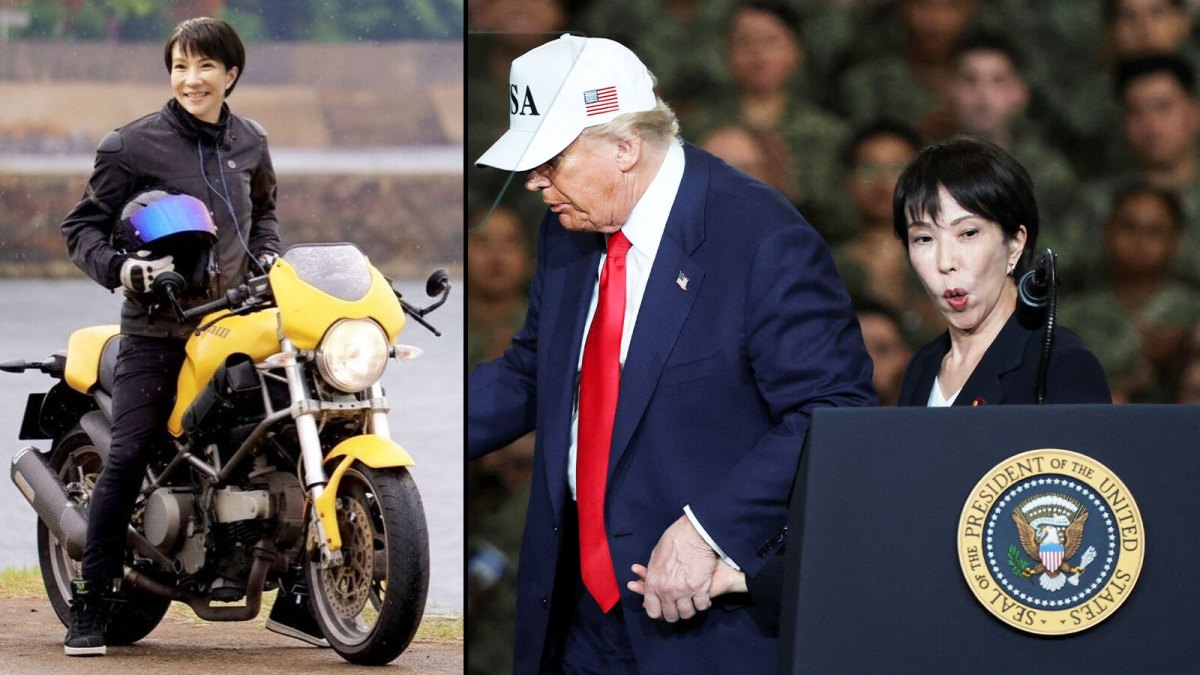

Since last week, Japanese politics has a new face — one unlike any it has worn before. At 64, Sanae Takaichi is not particularly young among postwar prime ministers. And as with all but six of her 32 predecessors, she is a member of the conservative Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). What makes Takaichi unique is that she is a woman, the first to have held real power in Japan since the shamaness/queen Himiko in the 3rd century. “The first woman prime minister — that’s a big deal,” Trump observed when he met her in Tokyo this week for her first big public engagement.

Flattering the US president is arguably the most important task of any national leader these days, and recent Japanese prime ministers have done a superb job. Abe got off to an energetic start by flying to New York the week after the 2016 election and personally delivering a gold-plated golf club to Trump Tower. This year Ishiba opted for a platinum samurai helmet. But both were anxious encounters, fraught with the potential for failure. Only Takaichi has given the impression of positively enjoying the company of the president.

On the deck of the aircraft carrier USS George Washington, which is based in Japan, she looked positively girlish this week as Trump introduced her to an audience of cheering sailors — grinning, raising her thumbs and jumping up and down while simultaneously pumping her arm into the air, a manoeuvre beloved of American cheerleaders but less instinctive for sexagenarian Japanese politicians.

“This woman is a winner — we’ve become very close friends all of a sudden,” Trump told the servicemen and women, only slightly polluting the atmosphere of chumminess when he added, “because their stock market today and our stock market today hit an all-time high.”

But who is Takaichi? And what, other than her gender, sets her apart from the succession of grey men who came before her?

• Trump tells Japan: Any favours you need, we’ll be there

She was born in 1961 in Japan’s ancient capital Nara, a tranquil and traditional city of temples, shrines and parks, with a picturesque population of sacred deer. Along with Osaka and Kyoto, it is in the region known as Kansai, a part of Japan proudly and self-consciously distinct from metropolitan Tokyo, with its own dialect known as Kansai-ben. In relaxed and informal moments, Takaichi speaks Japanese with a distinctive Kansai accent.

Her father worked for an automobile company and her mother was a police officer. In a memoir she wrote that she was a sickly child, frequently taken to hospital. But she describes it as a golden era, “a time when people felt their life got easier and more comfortable if they worked hard. It was a bright and cheerful time.” It is a vein of nostalgia that informs her politics: a simple, idealised Japan of the past that must be reclaimed from the soiled and sophisticated present.

By her own account she won places at the prestigious private Tokyo universities Waseda and Keio. Her parents declined to pay the fees, however, choosing to spend the money instead on the education of her younger brother. As a young single woman, she wasn’t allowed by her parents to live on her own even as a student. She had to commute from the family home to the less prestigious Kobe University — a six-hour return journey.

On the drums in a university band

She rode a motorbike and played the drums in a student heavy-metal band (her favourite song is Burn by Deep Purple). On her own initiative, after graduation she enrolled at the Matsushita Institute of Government and Management, an elite institution that has educated numerous senior politicians and business people. She completed an internship in the Washington office of the Democratic congresswoman Patricia Schroeder, a liberal and committed feminist. American friends from the time remember Takaichi’s energy and hunger to learn; none thought of her as a conservative, and certainly not the right-wing nationalist she has become.

For a female MP in Japan, though, it is easier to flourish on the right than anywhere else. Despite its declining popularity, the LDP still dominates politics. Other more liberal women who have succeeded in the party, such as Makiko Tanaka and Seiko Noda, were the daughter of a prime minister and a cabinet minister respectively, and inherited their male forebears’ support networks. Those who lack family connections need political sponsors; in the present party power lies with nationalist conservatives.

Takaichi fell in with a group of ambitious young LDP politicians who included Abe, the man who shaped her political career more than any other, repeatedly appointing her to his cabinet. A shared admiration for Abe, who was murdered in 2022 two years after leaving office, was the focus of the bonding exercise this week between Takaichi and Trump.

“He spoke so well of you, even before we knew what was going to happen and your ascension,” Trump told her. “I’m not surprised to see that you are now the prime minister, and he would be very happy to know that.”

Takaichi’s political ideas are a complicated matter, not as neat as the journalistic shorthand terms (such as “ultranationalist”) commonly applied to her. She shares Abe’s revisionist views about the way history is taught in Japanese schools. She objects to “masochistic” apologies for Japan’s wartime conduct and to teaching about the so-called “comfort women”, most of them Korean and Chinese women coerced into serving in wartime military brothels.

• Japan’s first female PM should make life easier for other women

She has been a regular worshipper at Yasukuni Shrine in central Tokyo, which honours Japan’s war dead as Shinto deities — a source of resentment in China and South Korea because of the executed war criminals included among them. She is outspokenly indignant about China’s increasing aggression and assertiveness, and especially its claim to the Senkaku Islands, which are controlled by Japan.

She supports closer relations with Taiwan and warns that a Chinese invasion of the self-governing democratic island would be an emergency for Japan. She wants to increase defence spending and to replace the “peace constitution”, written by the occupying Americans in 1946, with a new document that removes the restrictions on the country’s Self-Defence Forces.

Japan, by the reckoning of many economists, badly needs foreign workers to compensate for its shrinking and ageing population and to staff the care homes and construction sites the nation is no longer numerous enough to supply. But Takaichi opposes large-scale immigration, and has given credence to unsubstantiated online slurs about foreigners kicking Nara’s famous deer.

Many Japanese feminists regard her as an enemy rather than an ally — and yet there is no more impressive example of a Japanese woman who has overcome the lingering institutional sexism of her party and her society. It is for this reason that she admires Margaret Thatcher, another woman whose ascent through the glass ceiling caused more dismay than satisfaction to people on the left. “I don’t call myself a Japanese Thatcher,” she said in her most pronounced Kansai accent. “But for strong belief and practical determination, I won’t be surpassed by her.”

• Can Japan’s Iron Lady Sanae Takaichi fix the problems that sank last PM?

And perhaps in Japan in 2025, as in Britain in 1979, the glass ceiling could have been broken only by a conservative woman whose politics were reassuring to the old male establishment. Takaichi has talked frankly about the difficulties faced by female politicians, excluded from the late-night drinking sessions at which important decisions are made.

And for all her reverence for tradition, her private life has been far from conventional. She has been twice married to the same man, Taku Yamamoto, a former LDP Diet (national legislature) member, whom she divorced in 2017 and remarried four years later. She is stepmother to three of his children, but has none of her own. When they remarried he took on her name, becoming Mr Takaichi.

“[She] may be a lot of things, but she is serious, studious, open-minded, and not afraid to make up her own mind with fact-based arguments and analysis,” says Jesper Koll, an economist and long-term Tokyo resident who knows Takaichi.

Takaichi’s room for manoeuvre is constrained. Her early approval ratings are high, but as head of a minority coalition government she is in a weak position. Abe, who had large majorities in both houses, gave up trying to bring about constitutional change — his successor has no chance. At the Yasukuni Shrine’s autumn festival this month, Takaichi conspicuously stayed away, conscious of how far such a visit would have set back relations with Beijing and Seoul.

Far from making Japan great again, it is easy to imagine her simply fizzling, as so many of her male predecessors did, bogged down and frustrated by divisions in her coalition and tarnished by the difficulties of checking inflation that has caused the cost of rice to double in a year. But for now, at least, Sanae Takaichi’s is the face to watch.