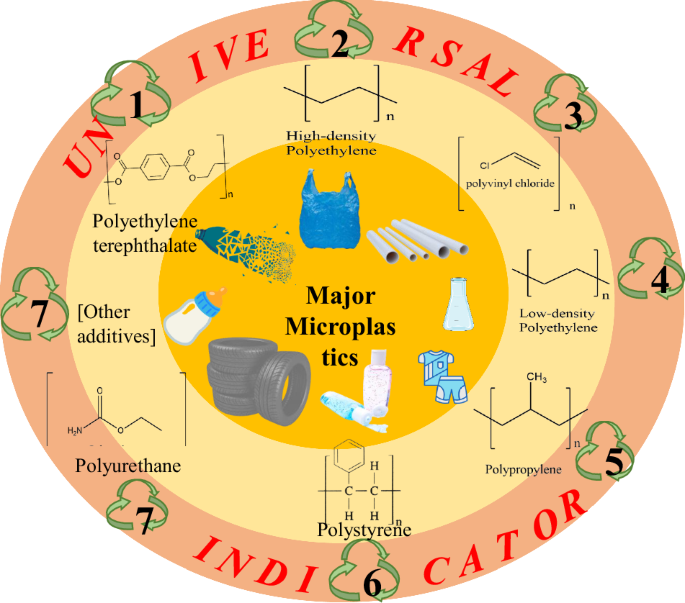

Soil systems are emerging as one of the largest sinks for MP contamination, with inputs arising from diverse anthropogenic sources and posing significant ecological and agronomic risks. MPs found in soils vary widely in chemical composition, size, shape, and origin24. Common polymers include Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), Polystyrene (PS), Polypropylene (PP), Polyester (PES), Polyamide (PA), Polyethylene (PE), Polyurethane (PUR), and Polyethylene terephthalate (PET), which occurs as fibers, ellipses, fragments, films, foam, pellets, particles, lines, and flakes25 (Fig. 1, along with their universal indicators). These MPs originate either as primary MPs, purposely manufactured for specific applications, such as drug vector applications, technical, industrial, and cosmetic abrasives, or as secondary MPs, resulting from the weathering and degradation of polymers found in food packaging, clothes, and plastic bottles26,27. These diverse forms and sources contribute significantly to the accumulation of MPs in soils, leading to growing concern across both environmental and agricultural sectors28.

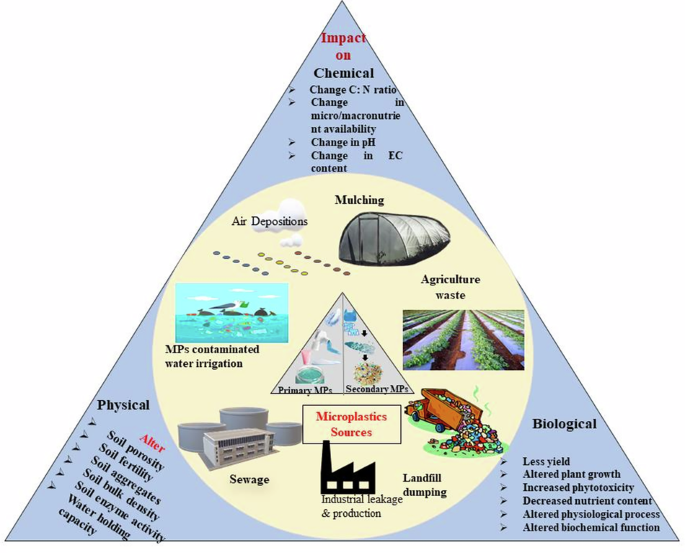

The presence of MP in terrestrial environments is now well-documented on a global scale, highlighting its status as a widespread environmental issue4. Compared to aquatic systems, soil ecosystems are more vulnerable to MP buildup due to frequent and varied land-based inputs. These include municipal sewage sludge29, residual plastic mulch from agricultural activities30, landfill leachate31, composts, organic fertilizers32, irrigation runoff33, and atmospheric deposition34 (Fig. 2). Such entry pathways are prevalent in both developed and developing countries, especially in regions characterized by intensive farming or proximity to urban waste infrastructure29,35,36. The persistent influx of MPs through these routes has turned the soil into a major reservoir of plastic pollution, posing long-term challenges to ecosystem function and food security.

Once introduced, MPs interact with the soil matrix and can induce significant changes in its physical, chemical, and biological properties7 (Fig. 3). For example, incorporation of 0.4% w/w PES fibers has been shown to enhance water retention and evapotranspiration but simultaneously reduce bulk density and compromise aggregate stability11. Similarly, 5% PE-MPs were found to decrease levels of dissolved organic matter and alter cation exchange capacity, affecting soil chemistry and its microbial community dynamics37.

These alterations in soil properties can lead to measurable impacts on plant systems. Studies by Yan et al.16,38 have reported that PE-MPs reduce germination rates and biomass accumulation in Triticum aestivum and Oryza sativa, likely due to disrupted soil structure and nutrient imbalances. Lactuca sativa has shown inhibited root elongation and reduced photosynthetic efficiency in MP-contaminated soils39. In Vicia faba, exposure to PS-MPs led to gentoxic effects, highlighting risk not only to plant health but also to reproductive capacity and yield40. Collectively, given the global importance of these species in food security and agriculture, it is crucial to understand the long-term ecological and agronomic consequences of MP contamination to come up with efficient mitigation strategies.

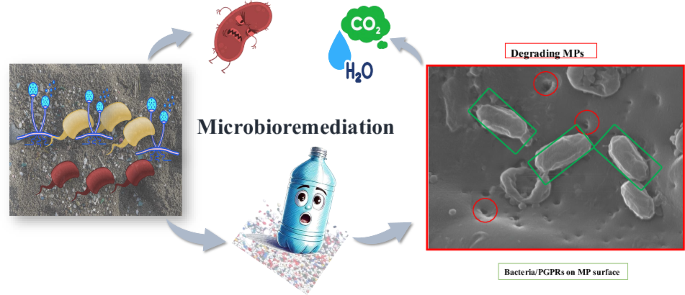

Microbial remediation of microplastics

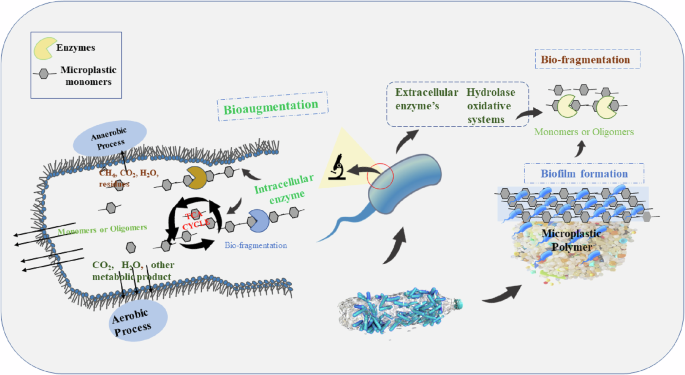

MP degradation in terrestrial environments is a synergistic process that comprises abiotic (e.g., thermal oxidation, photo-oxidation, or hydrolysis of polymers) and biotic (e.g., microbial enzymatic depolymerization, mineralization, and assimilation) processes15. Compared to abiotic degradation processes, biotic, especially microbial degradation, has the potential to cause additional plastic weight loss through biochemical processes of mineralization and adsorption. Aside from this, some enzymes such as manganese peroxidase (MnP), laccase, lignin peroxidases (LiP), and some hydrolases such as lipase, esterase, and cutinases can further help depolymerize MPs41. Over the past few years, publication rates with proof of the occurrence of microbial strains that degrade plastic as a source of carbon have also been increasing. Despite the encouraging potential for eliminating MPs from soil, the microbioremediation study is still in its initial phases. Therefore, in the following section, we have discussed the microbes capable of biodegrading MPs and their mechanism and advantages.

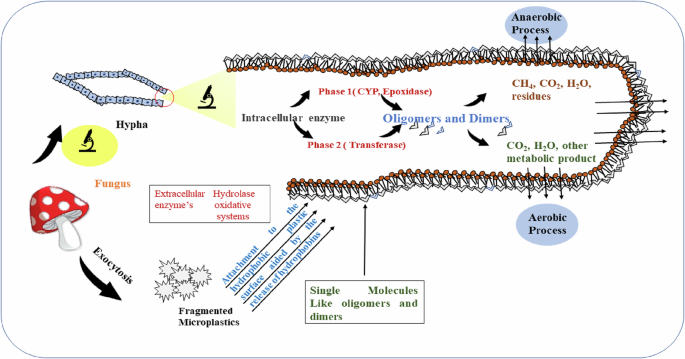

Among microbial candidates, fungi have shown particular promise in MP degradation due to their diverse nature and the presence of potent enzymatic systems, making them advantageous biological tools for MP degradation. The extracellular and intracellular fungal enzymatic activities can break down the plastic polymers into monomers, resulting in the production of non-toxic by-products like methane (anaerobically) and carbon dioxide and water (aerobic)42. A study by Paco et al.43 found that Zalerion maritimum fungal hyphae can metabolize the PE MPs with the help of extracellular enzymes like hydroxylase and intracellular proteolytic enzymes. Another study by Zhang et al.44 Observed Aspergillus flavus PEDX3, a filamentous fungus, can degrade High and Low-density PE by producing extracellular enzymes. This enzyme can hydrolyze the Hydrolysable alkanoates (HA) present in the PE matrix and release carbon dioxide, water, and hydrogen. However, the actual degradation mechanism and evidence of MP degradation by fungi are quite limited and require more research. A list of fungi possessing the ability to degrade the different types of MPs is given in Table 1.

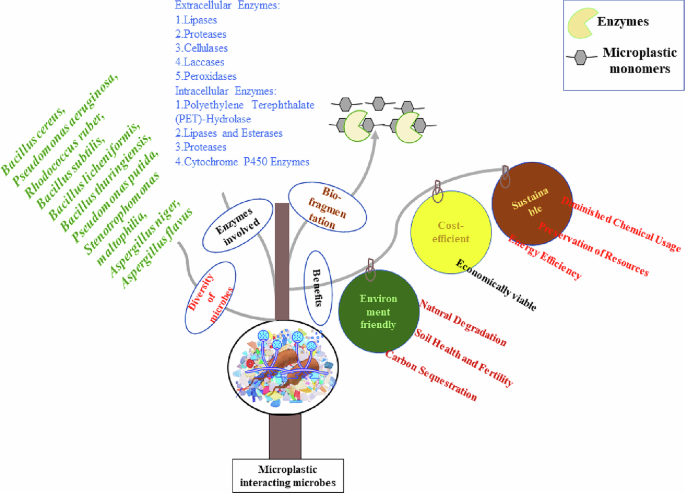

In parallel, bacterial remediation of MPs-contaminated soil is an emerging promising technique to combat the MP pollution in soil. Similar to fungi, bacteria can also degrade plastic polymers into monomers and produce methane under anaerobic conditions, whereas carbon dioxide and water under aerobic conditions45. In recent studies, various bacterial strains have been identified and isolated for their capability to degrade the MPs (Table 2). For example, Bacillus spp. and Paenibacillus spp. in Firmicutes, Streptomyces spp. in Actinobacteria, and Pseudomonas spp. in Proteobacteria are the groupings of bacterial strains implicated in significant plastic breakdown46. In addition to the well-documented roles of Firmicutes and Proteobacteria, actinomycetes represent another promising microbial group for MP remediation. As filamentous bacteria, they are known for producing a wide range of extracellular enzymes that can break down complex polymers. Actinomycetes, such as Streptomyces spp., are particularly noted for their ability to degrade different MPs and are a subject of ongoing research, as shown by Ameen et al.47 study on the degradation of polyvinyl chloride (PVC). The biofilm, formed by Streptomyces gobiticini, promotes the physical deterioration of the MP, which is ultimately the result of enzymatic release by bacteria. Another study by Auta et al.48 shows the MP degradation efficiency of two isolates, Bacillus cereus and Bacillus gottheilii. Among these, B. cereus caused 1.6, 6.6, and 7.4% MP particle weight loss for PE, PS, and PET MPs, respectively. Whereas, 6.2, 3.0, 3.6, and 5.8% were reported in the case of B. gottheilii for PE, PET, PP, and PS, respectively48. In certain bacterial communities, the high breakdown efficiency of certain MPs was also demonstrated. For instance, it has been shown that Pseudomonas putida isolated from agricultural soils can break down 92% of PU (in the form of Impranil DLNTM) in 4 days with the help of 45-kDa esterase49. A bacterial culture composed of Ideonella sakaiensis hydrolyzed the PET and related intermediates utilizing two different enzymes: ISF6 4831, a putative lipase for PET, and ISF6 0224, a tannase for mono (2-hydroxyethyl) terephthalic acid23 (Table 2). In these biological processes to depolymerize MPs, we need a variety of particular bacteria that act on particular regions or ecosystems. Among different microbes, Plant Growth-Promoting Rhizobacteria (PGPRs) are an important group of bacterial microbes that are gaining attention not only for their role in enhancing plant growth but also for their potential application in the remediation of MPs-contaminated soil50. This emerging bioremediation approach harnesses the unique capabilities of PGPRs to mitigate the environmental impact of MPs.

PGPRs establish symbiotic relationships with plants, particularly in the rhizosphere, and act as important rhizobacteria by influencing nutrient assimilation and the general rhizosphere condition of plants51. Along with PGP properties, some of them were discovered to contain enzymatic traits responsible for the MP degradation21. PGP enzymes of PGPRs, including esterases and lipases, play a crucial role in the breakdown of intricate polymer architecture, leading to the conversion of MPs into less toxic by-products52,53. Further, PGPRs may cause detoxification of intermediate degradation products. Besides this, the PGPRs also control the composition of root exudates, which in turn can influence the rhizosphere microbial population. The alteration of the rhizosphere by PGPRs can enhance microbial activity that degrades MPs. The interactions between PGPR and plants are more than bioremediation since they also assist in plant disease resistance and health promotion. The plant growth-stimulating impacts of PGPRs may promote increased stress tolerance under MP-polluted environments54,55. PGPRs are already used in agriculture as biopesticides and biofertilizers, adopting them as a soil bioremediation means may offer a green and integrated strategy for the management of MP contamination56,57. For instance, Bacillus spizizenii acts as PGPR by producing plant growth-promoting hormone-like Indole acetic acid, solubilizing phosphate, and increasing nitrogen metabolism at the same time, while degrading the Polystyrene MP21. Although current findings are limited to in vitro conditions, future research should focus on evaluating the field applicability of Bacillus spizizenii on different crop plants to further validate its dual function under realistic agriculture scenarios. Another PGPR, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain L381, degrades Phthalates, augmenting resistance in Oryza meridionalis in just 5 days58. Overall, the integrated interaction between PGPRs, plants, and microbes in the rhizosphere offers new possibilities for overcoming the impact of MP contamination on plant communities and soil health. Still, several challenges in this remediation process need to be overcome to be able to harness its full potential. Hence, In Later sections, we discussed the challenges and future directions for better understanding the potential of microbioremediation.

Mechanisms of Microplastic Degradation by Microbes

Several variables, such as the MP’s molecular weight and chemical structure, the type of microorganisms present, and several environmental factors, influence the degradation mechanism of MP59. Generally speaking, MP degradation mechanisms are intricate. The underlying mechanisms of MP degradation remain poorly understood and unclear. Hence, this section primarily tries to address the likely mechanisms of degradation by different types of microbes (especially fungi and bacteria/PGPRs-mediated).

Fungi are a varied group of microorganisms that exhibit extraordinary environmental and MP-type adaptation. According to the majority of current studies, the Aspergillus genus is the most well-known fungus group when it comes to the biodegradation of manmade plastic. Some Aspergillus species, A. clavatus60, A. fumigatus61, and A. niger62 isolated from various terrestrial habitats have been demonstrated to degrade PE, PU, and PP, respectively. Table 1 summarizes the list of Fungi involved in the degradation of different kinds of MPs. The enzymatic machinery of Fungi may target a variety of polymers63. The possible mechanisms of fungal degradation are as follows:

The first stage of polymer degradation is biodeterioration and penetration, leading to surface damage caused by abiotic and fungal forces acting both chemically and physically (Fig. 3). The fungus grows on the plastic’s surface and secretes enzymes that cut the polymer strands into smaller pieces, as shown by different fungal strains, especially Aspergillus sp64. The fungus creates a network of hyphae that release enzymes to further break down the polymer strand.

Further, the role of intracellular and extracellular enzymes in fungal adaptation and detoxification mechanisms has been highlighted in many research articles65. The intracellular enzymes like cytochrome P450 family epoxidases and transferases, especially phase I, are linked to oxidation reactions and conjugation, which aid in the metabolism of aliphatic, alicyclic, and aromatic compounds. They carry out a diversity of reactions, including desulfuration, sulfoxidation, epoxidation, deamination, and dehalogenation for the breakdown of these aromatic or aliphatic compounds of plastic polymers66. Utilizing cofactors like heme, NADPH + H + , and FAD, the cytochrome P450 families of enzymes aid in the maintenance of the integrity of the hyphal wall and the production of the spore wall. The extracellular enzymes found outside the cell include hydrolases oxidative system that can break down complicated polymers67,68. Other important extracellular enzymes from the class II peroxidases, including manganese, laccases, dye-decolorizing peroxidases, and lignin peroxidases from fungi, play an effective role in environmental cleaning up. Laccase, produced by lignin-degrading fungi, catalyzes the oxidation of non-aromatic and aromatic substrates, such as polymethylmethacrylate and polyhydroxy butyrate69.

The above-mentioned enzymes break down the MPs into secondary products, which are then efficiently assimilated by the fungus as a carbon source and release non-toxic byproducts. A summary of natural detoxifying processes found in fungi reduces the release of toxic byproducts after MPs break down70 (Fig. 3). This ensures that the restoration process does not introduce secondary contaminants into the environment, which is a crucial condition for sustainable and environmentally friendly remediation67,71.

Conclusively, the utilization of fungi-mediated microbial remediation presents a significant potential in mitigating MP contamination within soil ecosystems. Realizing the full potential of this sustainable and naturally inspired remediation technique requires an understanding of the complex interactions between fungi and MPs, optimizing conditions for fungal activity, and overcoming the obstacles associated.

For the attainment of a solution to the prevalent issue of MP contamination, bacterial-mediated degradation has attracted much attention toward research and innovation. Bacteria, with their wide variety of metabolisms, have the ability to degrade MPs and assimilate them enzymatically72,73. As a result, the key aspects of bacterial/PGPR-mediated degradation mechanisms are highlighted in this section (Fig. 4).

Due to their great diversity, bacteria harbor strains that are capable of decamping a number of MPs52. Different genera of bacteria have specific enzymes that target different structures of polymers, which makes them candidate solutions for the complex problem of MP pollution54.

Different Bacteria and some PGPRs produce extracellular enzymes such as lipases, esterases, and proteases, which help in breaking down the molecular bonds of MPs. Enzyme activities initiate the breakdown process, resulting in the disintegration of MPs into minor fragments that are more appropriate for potential uptake or utilization74. For instance, Ideonella sakaiensis 201-F6, a marine bacterium capable of producing PETase and MHETase enzymes, is able to degrade PET and medium-chain fatty acids (MHFAs), respectively23. These enzymes hydrolysis the PET to short oligomers and cleave the MHFA to acetyl-CoA and CO2. However, microbial biodegradation of MPs is a multifaceted interaction between enzymatic activity and microbial physiology, with intracellular enzymes being central to the degradation of these recalcitrant pollutants. The intracellular enzymatic process is within microbial cells and involves a series of important steps. Bacillus sp., the famous PGPR strain, can biodegrade plastics such as PE, PP, PS, and PVC by producing enzymes such as polymerases75,76. These enzymes can hydrolyze the ester, amide, and glycosidic linkages of plastics and release fatty acids, alcohols, and monomers. Other microbes like Rhodococcus sp., a gram-positive bacterium, and PGPR are reported to degrade PE and PP by the action of lipases and esterases. These enzymes are capable of hydrolyzing the ester bond in the plastics and producing fatty acids and glycerol77. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a gram-negative bacterium, has been known to biodegrade the PE through the intracellular production of an enzyme, Pyrrolidonyl Aryl Amidase (PAM). This enzyme is capable of hydrolyzing amide linkages on the backbone of the PE and releasing pyrrolidone carboxylic acid (PCA), a biodegradable compound78. All these show that by the interplay of extracellular and intracellular enzymes, the bacteria break the MP polymers, release their monomeric form, and ultimately degrade them into harmless gases, CO2 and H2O.

Bacteria are known to form biofilms on the surface of MPs. These biofilms form an enzymatic degradative microenvironment that is optimal and protects the bacteria from harsh environmental conditions (Fig. 4). Synergistic action within biofilms renders bacterial degradation efficient and stable over a longer time79. For example, Bacillus sp. forms a biofilm on the MP surface and degrades MPs by the production of enzymes like lipases, esterases, and polymerases. The enzymes hydrolyze the ester, amide, and glycosidic linkages in the plastic/MP substrate80. Enterobacter asburiae YT1 and Bacillus sp. YP1, two gut bacteria strains isolated from waxworms, also form biofilms on the PE-MP surface and depolymerize it by releasing enzymes such as lipases. The enzymes are able to hydrolyze the ester linkages of PE MPs and release fatty acids81. These are a few ways through which Bacteria/PGPRs are able to use their biofilms to biodegrade plastic/MP pollution.

However, there are several limitations and drawbacks to this process, such as low specificity, stability, efficiency, and availability of the enzymes; resistance and toxicity of some plastics; and environmental conditions that affect the rate of degradation. Therefore, more research is needed to maximize microbial-mediated biodegradation of MP pollution for practical applications. Explanation of bacterial modes of action, revelation of genetic heterogeneity, and mitigation of pragmatic concerns will further propel progress in this bioremediation method toward pragmatically effective, large-scale application in pursuit of a plastic-free, eco-friendly future.

Benefits of microbial remediation

For issues like MP soil ecosystem contamination, microbial remediation is a technique with vast potential as an environmentally friendly solution. In preserving and restoring environmental integrity, and ensuring that the natural character of microbes provides a sustainable and green solution. The key advantages related to microbial remediation are described below (Fig. 5).

Microbial remediation has a very robust package of benefits, especially if one looks at cost-effectiveness and the sustainability aspect.

Microbial remediation reduces the demand for energy-intensive technologies such as excavation and landfilling, which entail huge material, energy, and land inputs. The process reduces the environmental impact of conventional cleanup technologies and conserves resources through the use of the inherent ability of microorganisms.

Microbial remediation decreases the reliance on man-made chemicals and harmful substances that are typically used in traditional cleanup procedures. This environmentally friendly process decreases human health risks, environmental contamination, and long-term environmental damage from chemical treatments.

As opposed to traditional remediation technologies, microbial remediation is a cost-saving option. Since microbiological approaches are less expensive in terms of infrastructure, materials, and machinery, larger areas can be treated at the same time and at no greater cost.

In addition to its practical and economic advantages, microbial remediation also provides substantial environmental benefits that enhance soil health and ecological balance, like:

Bioremediation capitalizes on the natural ability of microbes to break down substances into harmless, less complex forms. The process curtails the concentration of long-lived pollutants in the soil community through the acceleration of the natural biodegradation process, thus diminishing the long-standing effects on the ecosystem.

Soil fertility and health are maintained to a large degree by microbes. Microbiological remediation creates a good environment for plant growth, biodiversity conservation, and ecosystem stability by improving soil structure, organic matter decomposition, and nutrient cycling.

The treatment reduces the formation of toxic by-products, as opposed to chemical treatment processes that can introduce residues or secondary pollutants. Through the breakdown of MPs into non-toxic by-products of water, carbon dioxide, and biomass, microbial treatment reduces ecological interference risk and associated pollution.

Finally, microbial remediation provides a solution to a vast array of issues caused by MP contamination, such as soil deterioration and toxicities to plants. Microbial solutions ensure the ecological balance, Soil fertility, and health by utilizing the inherent ability of microorganisms. The application of microbial-based technologies will create a model for a green and eco-friendly solution to one of the major environmental problems of current times, i.e., MP pollution.

Research gaps and future opportunities

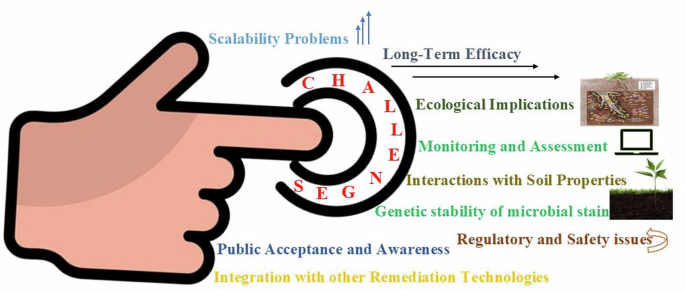

Bioremediation has the potential as a long-term, environmentally friendly remedy for soil MP pollution, but several research gaps and implementation that require careful consideration and concentrated research (Fig. 6). One of the foremost implementation gaps in advancing bioremediation technologies lies in overcoming technical constraints, particularly those related to scalability, long-term microbial stability, monitoring tools, and genetic reliability under field conditions.

The scalability of the micro-bioremediation methods is one of the major issues to resolve. Real-life conditions in fields offer a true challenge for duplicating the success of lab-scale experiments in the real world. Optimization of microbial remediation in various matrices of soil, climatic factors, and contamination levels is necessary for application at the practical scale. Therefore, a structured approach is needed to bridge the gap between laboratory success and real-world application. For example, a framework for a field trial using a promising PGPR strain in a target crop system would aim to evaluate its dual effectiveness in mitigating microplastic pollution while concurrently enhancing plant growth and soil health under natural field conditions, this framework would measure both MP degradation and key plant growth parameters to bridge the gap between lab findings and practical application.

In the long run, there are numerous problems linked to the sustainability of microbial activity and remediation efficiencies. To gain long-term performance, there should be an effective exploration of the dynamics of the microbial population, their reaction under varying environmental situations, and potential resistance development among MP strains.

One of the unsolved issues is developing effective and practical monitoring techniques for real-time tracking of micro-bioremediation performance. Quantifying the extent of MP degradation, potential by-products, and overall environmental effects of microbial interventions relies on efficient assessment protocols.

Microbial strains employed for the degradation of MP can deteriorate over time as a result of mutations becoming less efficient and require redesigning now and then. Furthermore, horizontal gene transfer poses a threat in which planned genes are moved into non-target organisms and create ecological problems, such as the advances in antibiotic resistance82. In addition, such microbes are capable of adapting to environmental pressures, where they shift their degradation mechanisms, which may reduce their efficacy and necessitate further adjustments.

The figure outlines key obstacles in microbial remediation, such as technical issues in terms of scalability, genetic stability, and monitoring, Social and public concerns in terms of regulatory and safety concerns, public acceptance and awareness, ecological effects, and Economic considerations in terms of synergy with other remediation technologies.

In parallel with these technical concerns, issues related to public perception, biosafety, and regulatory frameworks also present significant barriers to widespread implementation.

The use of microbes for environmental cleanup is highly controlled, involving strict approval procedures that include extensive risk assessment to guarantee ecological and human safety. There are great biosafety risks involved in releasing these microbes into the environment, such as the potential for ecosystem disruption and the production of toxic byproducts. There is also no harmonized global policy on the safe utilization and disposal of these microbes, making it a reason why regulatory policies need to be harmonized for their safe utilization.

Microbial environment remediation can be opposed by the public based on perceived safety risks, environmental impacts, and ethical issues. Public opposition against genetic engineering can knee the use of these technologies, making it essential to increase the awareness of the public towards the severity of MP pollution and microbial remediation as a solution. The involvement of stakeholders such as the local communities, policymakers, and environmentalists is crucial in trust building and generating public acceptance of these programs to enable their effective implementation.

Extensive studies are necessary to establish the manner in which microbial interventions impact soil microbiota, non-target microorganisms, and general ecosystem functions. Optimizing efficient MP remediation with minimal ecological disturbance is a challenging but essential challenge.

The complex interaction that occurs between microbial parameters and the numerous physical and chemical properties of various soils is yet another parameter to research. It is also crucial to identify how factors such as soil content, pH value, and water content affect the efficacy of microbioremediation so interventions may be tailored to specific environmental settings. To address this, Table 3 synthesizes current knowledge on the influence of key soil properties and outlines testable hypotheses for future research in this area.

Alongside these ecological and social considerations, economic and logistical factors also influence the large-scale feasibility of microbial remediation strategies.

It is possible to couple microbial remediation with other technologies, such as physical, chemical, or phytoremediation technologies, to produce a synergy that would increase the overall effectiveness of MP cleanup. However, integration of this kind must be controlled carefully so that these techniques do not conflict with one another. Integration of these hybrid techniques at a large scale is also plagued by cost and logistics problems, which need to be overcome for these to be utilized at a large scale. Compatibility with current infrastructure and technology is also extremely important to the integration of remediation techniques. To fill these gaps, governments, stakeholders in business, and researchers have to collaborate. By overcoming these challenges, the micro-bioremediation process can become a promising, universally applicable solution to the common problem of soil ecosystem contamination by MPs.

This review places a strong focus on the vast potential of microbial remediation as a means to combat MP contamination in soil ecosystems. The review brings out the effectiveness of various microbes, such as bacteria and fungi, in degrading MPs through various processes, from enzymatic reactions to the development of biofilms. The review encompasses recent studies from 2017–2025, evidence of immense progress in identifying these microbial interactions and their exploitation. Despite these advancements, several challenges remain, including the need to adapt laboratory findings for practical field use, ensure the sustained effectiveness of these methods over time, and evaluate their broader environmental effects. Moving forward, research should focus on exploring a wider variety of microorganisms, as very little research has been done on PGPR as a bioremediation tool. Future research should focus on unraveling the specific biochemical pathways involved in MP degradation and creating scalable, eco-friendly solutions to manage MP contamination effectively.