“By reading Laxness, one gains a kind of understanding of the world — you’re not just reading it for the sake of reading,” says Einarsdóttir.

Composite image/AFP/mbl.is/Ól.K.M.

The works of Halldór Laxness rank among the most important literary achievements in Icelandic history. Literature, as Iceland’s core cultural heritage, has long been what unites the nation—a nation without grand cathedrals or monumental architecture to boast of.

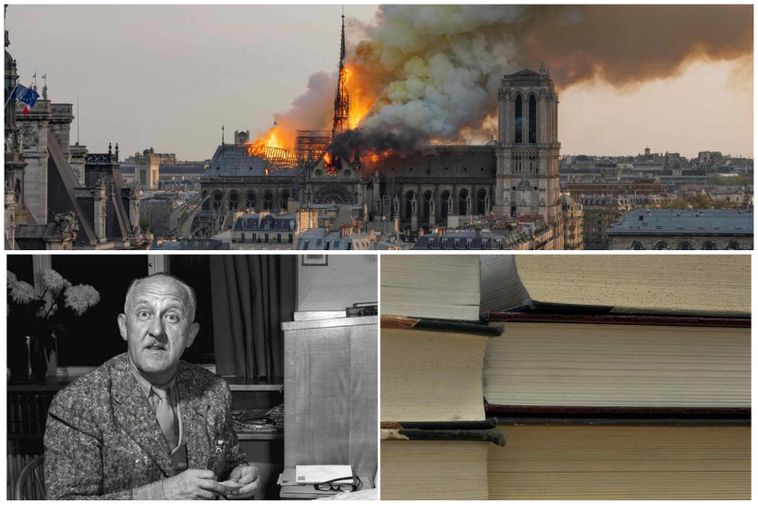

Thus, when discussing the disappearance of Laxness’ books from high school curricula, one might say that Iceland’s Notre Dame stands in flames.

This is how journalist, playwright, and literary enthusiast Elínborg Una Einarsdóttir describes the situation in Dagmál on mbl.is.

“I think it’s entirely comparable—it’s a huge loss. We’re losing something from the national soul. Literature has always been what has held us together,” she says.

Students need guidance, not abandonment

Earlier this month, Einarsdóttir reported that the works of Halldór Laxness are rapidly disappearing from Icelandic high school reading lists. Fewer than one-third of students now read a Laxness novel as part of their required Icelandic studies, and Independent People is assigned in only four out of twenty-nine schools. Teachers cite declining reading comprehension, shrinking vocabularies, and changing times as the main reasons.

Asked about reports that some teachers have given up teaching Laxness because students no longer read at home, Einarsdóttir said she could understand that it may be harder to teach such works today—but she also knows teachers who strongly disagree with giving up.

A teacher at Menntaskólinn við Hamrahlíð, where Independent People is still taught, told her that some students not reading at home is nothing new—and that doesn’t mean teachers should stop trying. The books still speak to students, she said, and with guidance and good teaching, most of them understand and connect with the material.

“There’s something beautiful about that”

Einarsdóttir shared an example from social media: a teacher described a student who said they hated Independent People because it was so depressing—but at the same time, the student felt such a strong connection to the characters that they wanted to “go into the book and help Ásta Sóllilja.”

“There’s something so beautiful about that,” says Einarsdóttir.

She adds that reading Laxness is not about ticking boxes on a curriculum but about engaging with profound literature and deeply human characters.

“By reading Laxness, you gain a kind of understanding of the world. You’re not reading it just to get it over with.”

Is Iceland’s Notre Dame burning?

Asked whether abandoning Laxness means losing something essential from Iceland’s cultural identity, she answers firmly:

“No, I don’t think that’s too dramatic. These are some of the most important literary works of our nation. Perhaps only the Icelandic sagas—like Njáls saga—are more central to our culture. But even those are slipping away. I think this is a serious matter because our cultural heritage as Icelanders is our literature.”

As biographer Halldór Guðmundsson once told her, Icelanders cannot point to magnificent churches or castles as cultural treasures—but they can point to a small hill in the South and say, ‘That’s where Njáls saga happened.’

“That’s where we are now,” Einarsdóttir concludes. “Many high school students haven’t even heard of Laxness. And at that point, I can’t help wondering—maybe our Notre Dame really is burning.”