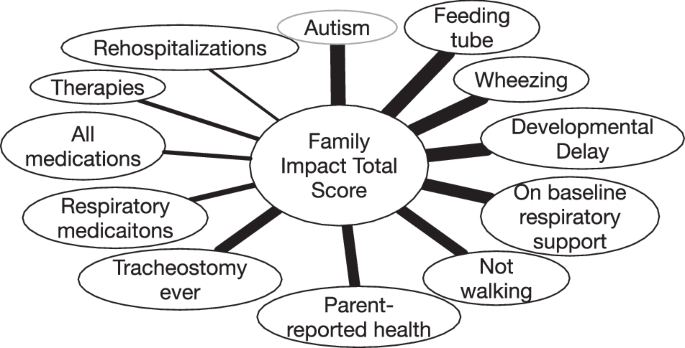

We present parental HRQoL and family function outcomes for a referral cohort of children with BPD, the most severe cohort reported on a number of respiratory and developmental outcomes [11]. Compared to previous studies of families impacted by BPD that used the PedsQL FIM, parental HRQoL and family functioning were lower in all sub-scores in this more severe cohort [1, 7]. Scores were similar to one other study in a severe cohort [21]. HRQoL and family functioning scores were not higher in parents of older children, despite improvements in children’s physical health, including the decreased respiratory morbidity and more positive parental assessments of the child’s overall health, that we have previously reported [11]. A diagnosis of autism, a feeding tube, and having wheezed in the past year were most strongly correlated with HRQoL total scores, though many other respiratory and developmental outcomes also had important impacts on the family. Three elements of our findings warrant further discussion.

First, parents of older children did not report improved parental HRQoL and family functioning compared to parents of younger children, as would be consistent with studies in less severe BPD cohorts [1, 7,8,9]. This finding suggests that adaptation and improved respiratory symptoms seem insufficient to better family life. A plausible explanation is that although physical health of the children improves, the neurodevelopmental sequalae weigh more heavily on parents as the child ages. Nearly half of our participants were told by a doctor that their child had developmental delay and almost all of the children required an IEP for school [11]. Autism and developmental delay were also some of the most strongly associated outcomes with both parental QoL and child QoL in our cohort [11]. Problems with development may also lead parents to worry about future academic success and their children’s’ potential to gain independence, further impacting QoL. The shifts in the specific questionnaire items that were most problematic suggest a shift from difficulty with household tasks to concerns about how their child will engage with society and how others will react to their child’s disabilities. The severity of disease in this cohort likely explains the discrepancy between our reported stagnation of family outcomes, and other studies reported improvement. The impact on parents of school-age children with such severe BPD sequelae has not previously been reported.

Second, we found that many medical factors negatively impacted parental HRQoL and family functioning, presumably by increasing the burden of caring for children with severe BPD. Our findings that the severity of respiratory disease correlates with parental HRQoL and family functioning are consistent with prior work done in more mildly affected populations [1, 7]. However, our data suggest that respiratory morbidities do not convey the whole story, as autism and other developmental sequelae which are far more common in patients with severe BPD also have a major impact on families. While tracheostomies have often been used as an indicator of severe disease, they are no more correlated with parental HRQoL than the ability to walk or developmental delay. Surprisingly, however, tracheostomies were correlated more strongly with parents’ report of their own HRQoL than parent-reported child HRQoL. This is consistent with some prior work and further supports the hypothesis that while the parent’s perceived impact of the tracheostomy on the child was minimal, parents themselves were overwhelmed by the pressure of caregiving, were experiencing adverse effects on their sleep, and were worried about their child’s health after tracheostomy [22]. We were surprised to find that CP, poor weight gain, vision and hearing impairment were not associated with PedsQL FIM. Perhaps conditions that are stagnant rather than progressive or episodic better allow for parental adaptation. Overall, our findings suggest researchers should measure a wide variety of outcomes—rather than rely on respiratory morbidity— to capture the effect of severe BPD on families. Additionally, these results demonstrate the importance of clinicians understanding and addressing the many ways that a child’s clinical trajectory impacts parents over time.

Third, many of the issues cited as most problematic to family HRQoL are modifiable with additional support, particularly financial support. These issues include feeling tired, feeling like people don’t understand their situation, and lacking time for chores and social activities. Providing additional resources for families, such as access to respite care, home nursing, medical daycare, support groups and counseling has the potential to substantially improve the experiences of parents of children with BPD. Past studies have found that parental income in families of chronically ill children predicts positive quality of life and that peer support groups are helpful in reducing distress [23, 24]. Additionally, home nursing is highly valued by these families [25, 26]. Increasing access to resources like financial support and nursing for families of children with severe BPD would likely improve familial HRQoL and functioning. Several studies have demonstrated that increased family functioning leads to improved adherence to medical regimens and control of symptoms in children with chronic conditions [27,28,29].

Our study design has strengths and limitations. First, our cohort consists of children referred to a specialized program at a single center. However, this is also a strength because given the severity of BPD required for referral to the NeoCLD program at CHOP, our patient cohort provided an opportunity to study parental HRQoL for a common condition in its most severe form. This data is applicable to other centers that care for patients with severe disease. Second, our data collection overlapped with the beginning of the Coronavirus-19 pandemic, which could have led to further challenges for the families. However, our data largely represents outcomes prior to this period. Another limitation is that our data on post-discharge diagnoses are gathered through parental report rather than medical records. Still, it would be unlikely for parents to misremember important diagnoses, especially to overestimate. Another limitation is that our study was cross sectional rather than longitudinal, so age-related differences may in part reflect changes in standard care over time. Additionally, given that we interviewed each family at one moment in their lives, the circumstances outside of their child’s health status at that time may have influenced their responses. Finally, our response rate was relatively high for a follow up study [7, 30], and the baseline similarities between responders and non-responders are reassuring against sampling bias (Supplementary Table 1).