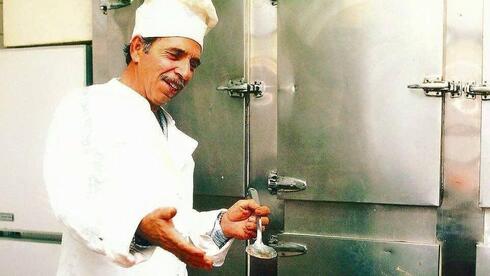

Tel Aviv, 1962. A handsome Bulgarian immigrant named Arnold Benish arrived in the young city, wearing a tailored suit and carrying a monocle in his pocket. Not long after, he placed a hot tin can beside the old tennis courts in Tel Kasila and began selling simple eggplant sandwiches.

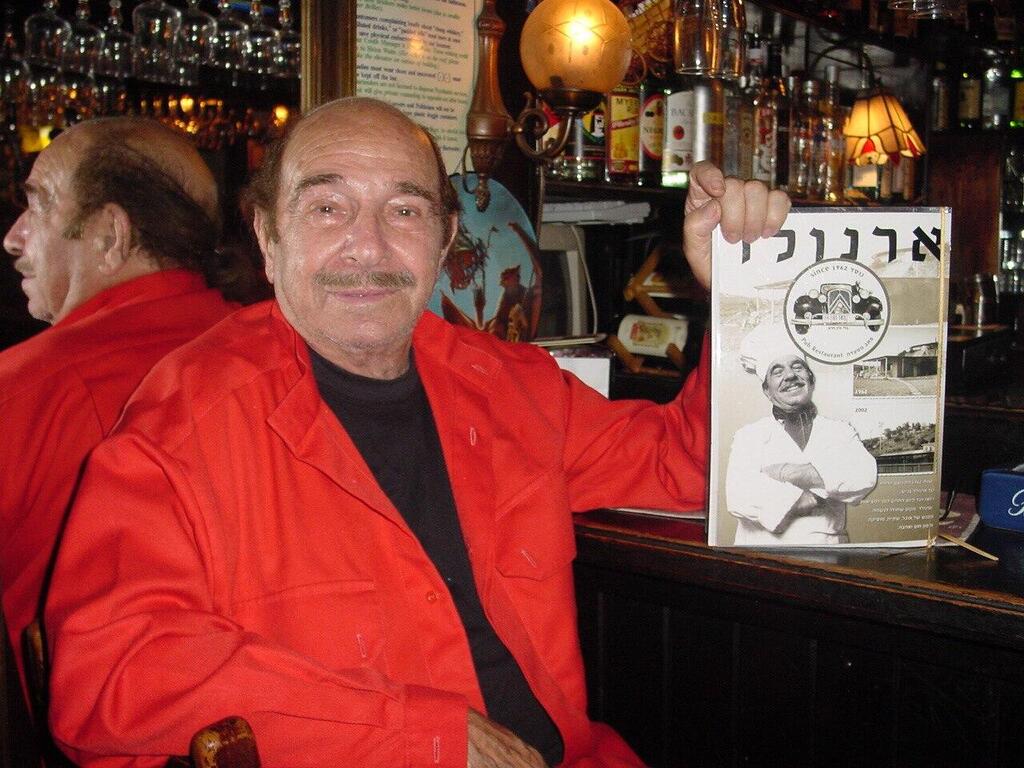

Within days, his little idea became a local obsession. Word spread, the line stretched all the way to the Yarkon River, and Arnold — the “lord with a sandwich in his hand” — became a legend. That’s how Arnold’s, the bar-restaurant that celebrates 70 years this year, was born.

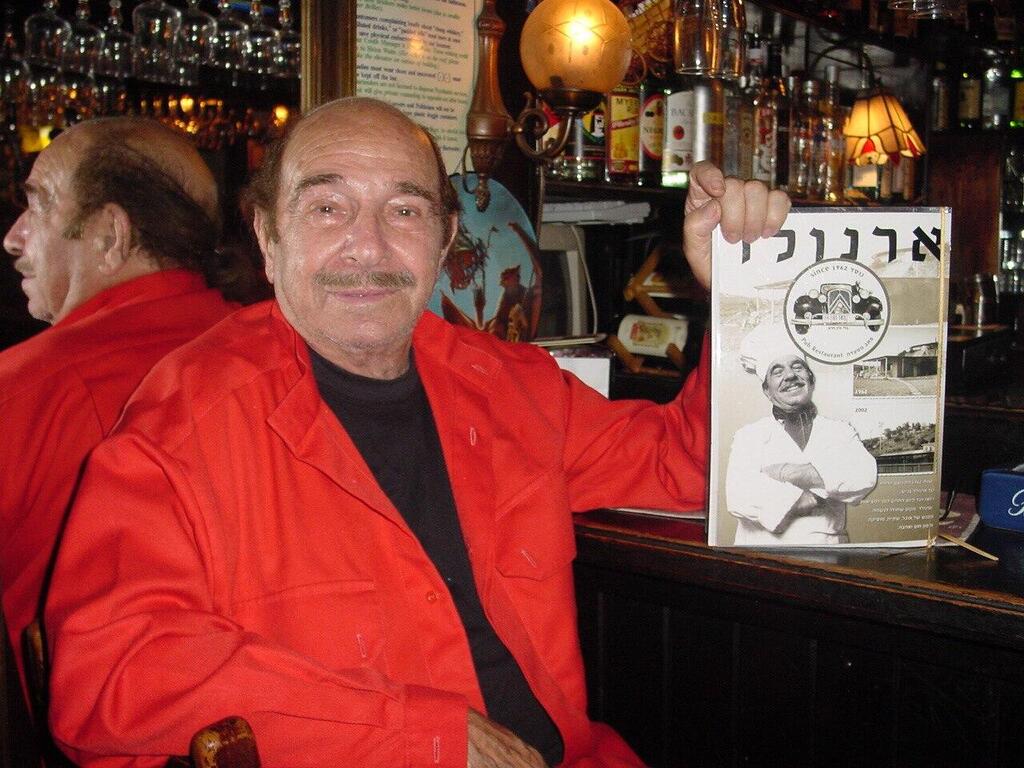

5 View gallery

Arnold Benish

(Photo: Family album)

Over the decades, Tel Aviv has seen countless bars, cafés, and restaurants come and go. Culinary trends have risen and vanished. Yet some places not only survive time — they capture it. Arnold’s is one of them.

Today, three generations of the Benish family still run the restaurant, serving the same classic dishes in the same spirit. Arnold’s son Yoav, 74, and his grandsons Mikey, 39, and Yonatan, 43, manage the spot, located for the past two decades in a leafy corner of Shitrit Street, next to a small grove in the Hadar Yosef sports complex.

“Among all the bars around today, Arnold’s remains a living memory of what used to be old Tel Aviv,” says Yoav.

In the 1960s, when Tel Aviv was still a small coastal town, Arnold’s was one of only four serious restaurants in the city — alongside Casbah on Yirmiyahu Street, Alhambra in Jaffa, and Gondola on Pinsker. Its clientele included the cultural and political elite: actors, ministers, writers, and business figures. From Buma Shavit and Mayor Shlomo “Chich” Lahat to Ephraim Kishon — everyone came to Arnold’s for cognac, cigarettes, and a perfectly paced three-course meal.

Benish was 24 when he immigrated to Israel, with no formal culinary training but plenty of charm. He opened a tiny stand beside the old tennis courts in what was then Tel Kasila — now the site of the Eretz Israel Museum — selling hot eggplant sandwiches to tennis players. Within days, lines snaked around the block, and even horseback riders stopped by for a bite. The scene, people recall, felt like something from an old film: people pausing, chatting, eating, and moving on — always wanting more.

5 View gallery

“A true lord with a theatrical flair.” — Arnold Benish

(Photo: Family album)

“It started as a stand and became a restaurant almost overnight,” Yoav remembers. “My father realized people were coming for the eggplant, so he turned it into a brand. To this day, if you tell a taxi driver ‘take me to the eggplants,’ he’ll know exactly where to go.”

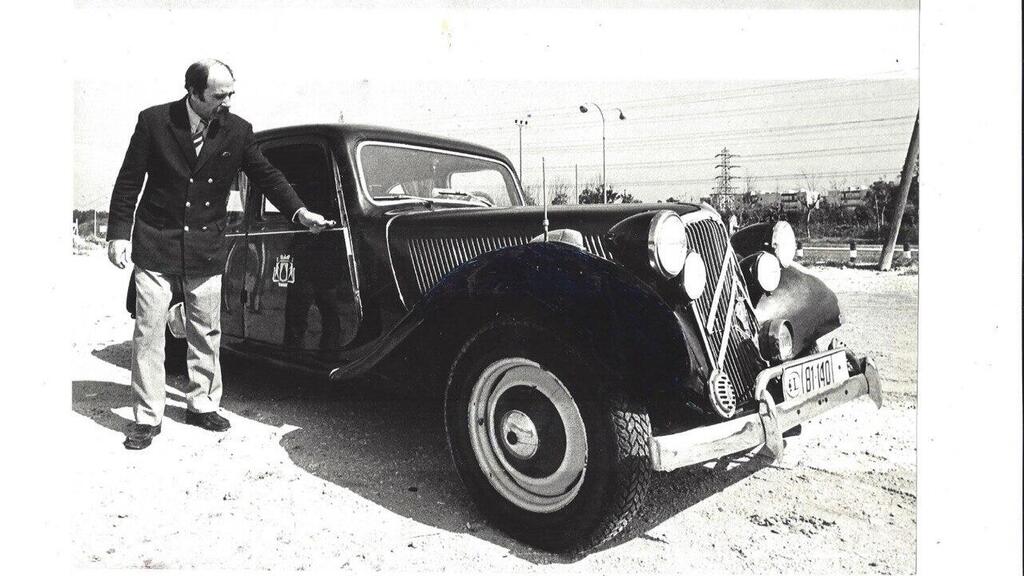

Arnold himself was a character — a true showman. He wore three-piece suits, kept a monocle in his pocket, and drove an old Citroën decorated with two crowns and an eggplant painted between them. “That was my father,” Yoav says. “A lord with an eggplant sandwich.”

As a child, Yoav would ride his bike to the restaurant after school, watching his father shave, perfume himself, dress impeccably, and head to work as though stepping on stage.

In the early days, there was no menu and no waitstaff. Arnold himself would walk to each table, sit down on a stool, and recite the day’s dishes. “If something wasn’t in the kitchen, he’d make it up on the spot,” Yoav recalls. “It was a one-man show. He could sell food in six languages, and every table got its own performance.”

After taking orders, he would cook everything himself. It worked. People saved money just to eat at Arnold’s. “It was a matter of status,” Yoav says. “He managed to sell eggplant for the price of filet steak — and everyone gladly paid.”

For Arnold, eggplant was the perfect ingredient. “It’s versatile, limitless,” Yoav explains. The menu back then featured eggplant jam, moussaka, eggplant with tahini, and eggplant with yogurt — many of which are still served today.

5 View gallery

He lived to see the new place, two years before he passed away. — Arnold Benish

(Photo: Family album)

Over time, Arnold’s became a beloved Balkan-style restaurant and a magnet for anyone seeking good food and atmosphere. Arnold was also a passionate collector of antiques — old weapons, gramophones, samovars, and vintage cars — many of which still adorn the restaurant’s walls.

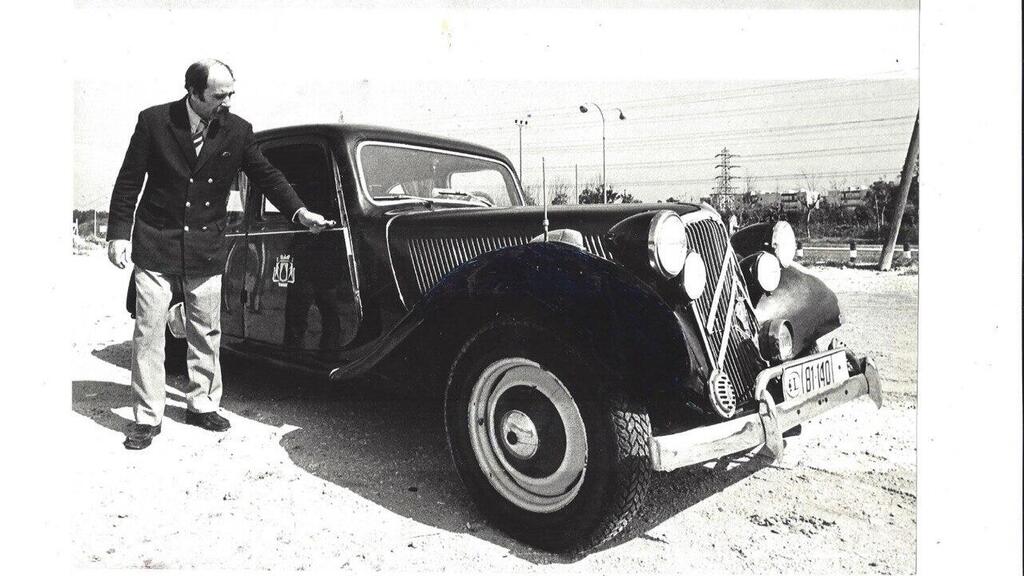

In 2005, after losing a tender for the original location, the family had to close. “It was like destroying nostalgia for 500 dollars more a month,” Yoav says bitterly. “In Europe, places like this are preserved. Here — they’re erased.”

But a few months later, Yoav noticed a new building on the edge of a park, knocked on the door, and said, “I’m Arnold.” The name worked — he got the lease. The stained-glass windows, furniture, and bar were all recreated exactly as before. Two years later, in 2007, Arnold passed away — but not before seeing the new restaurant and giving it his blessing.

“This place has three generations of customers,” says Mikey. “Grandfather, father, and son at the same table. It’s not just a bar — it’s home.” But as in any family, there’s a price. “I never had a Friday dinner at home,” Mikey admits. “Dad was always at the restaurant. Only later did I understand that’s the cost of loving this place.”

5 View gallery

Yoav Benish

(Photo: Yariv Katz)

Yoav acknowledges that running a restaurant is brutal. “Restaurants open and close all the time. Anyone who survives is a hero,” he says. “After the army, my father forced me to study hotel management in Switzerland. I didn’t want to, but in the end I realized he had no one else to pass it to. In the beginning, customers compared us — ‘your father used to do it this way.’ That hurt. Eventually, I learned to accept it. He was the type who made this place what it is.”

“I’m old-school,” Yoav admits. “When the younger generation canceled my handwritten reservation book and switched to digital, it was a crisis for me. I used to recognize customers by their voices on the phone. I knew who they were, what they liked to drink, and where they liked to sit. That’s real hospitality.”

The third generation — Mikey and Yonatan — try to preserve that spirit while adapting to the times. “We’re not Eyal Shani or Chaim Cohen,” Mikey says. “We’re not trying to be the most culinary place in the world. We’re trying to be the most human. This is a place of soul, not trends. No natural wines, no chef’s specials — just our truth.”

5 View gallery

Yoav and Mikey Benish

(Photo: Yariv Katz)

Part of that truth includes sticking to their principles. “For years, Dad sold what he called ‘low beef’ — pork,” Yoav laughs. “We also serve shrimp. We don’t force anyone to eat it. Whoever doesn’t want to, doesn’t. We don’t preach — we just feed.”

Since October 7, the restaurant no longer opens on Saturdays. “I want to be with my kids,” says Mikey. “I grew up with a father who was always at the restaurant. I don’t want my children to feel the same.”

What would Arnold say if he could see the place today?

“He’d probably say it’s not good enough,” Yoav laughs. “But deep down, I think he’d be proud. We’re continuing his name, even if the style has changed.”

Mikey smiles: “Every generation has its stubbornness. Just like Grandpa never compromised on his style, we’re not compromising on ours.”

Yoav nods, recalling one last story: “When we moved to the new location, Dad said he’d give me the money if I designed it exactly the way he wanted. I refused. I preferred to take a bank loan and do it my way. Every generation has its own way. We don’t want to be a giant brand — just live with dignity. If there’s peace and stability, we’ll go on for years. But a few more wars like this — and I’m not sure we’ll survive.”