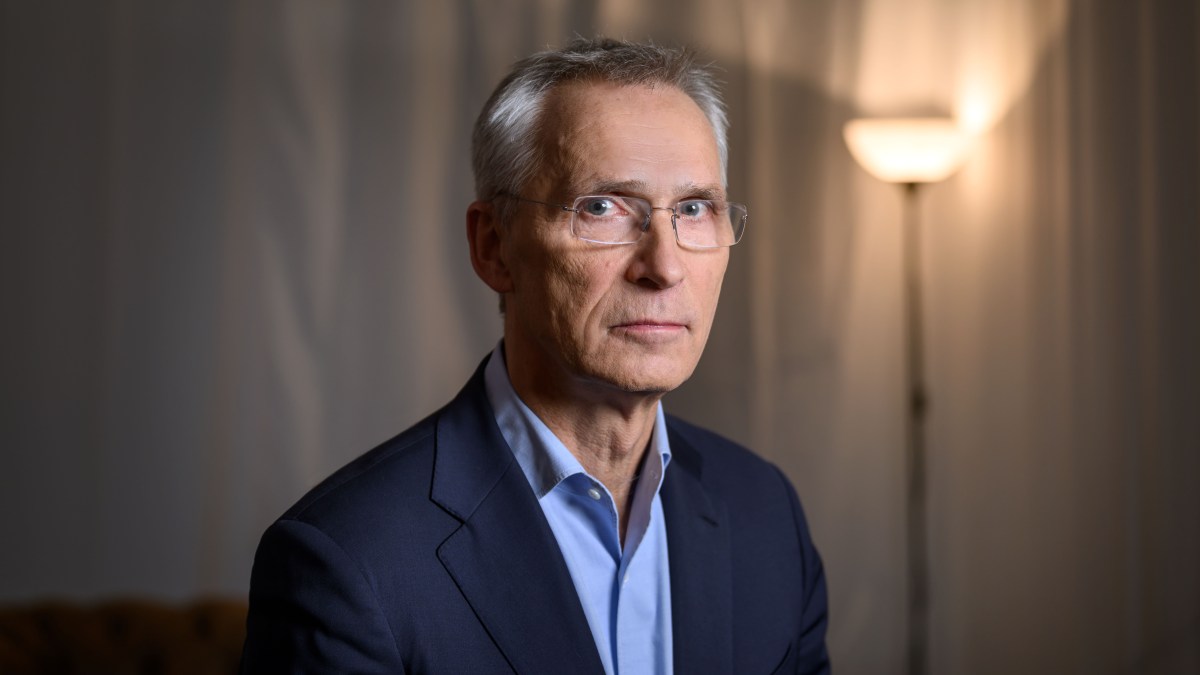

Nato’s former secretary-general has described the “painful moment” in February 2022 when he refused President Zelensky’s desperate plea to impose a no-fly zone over Ukraine.

Jens Stoltenberg said he feared their conversation might be the last phone call the president would make.

“We all feared for the life of President Zelensky and his family,” he said. “He called me from a bunker in Kyiv with Russian tanks just up the road. And he said: ‘I accept you’re not sending in Nato ground troops, though I disagree. But please close the airspace. Prevent the Russian planes, drones and helicopters from flying and attacking us.’

“And he also said that ‘I know Nato can do it because you’ve done it before’.

“Nato closed the airspace over Bosnia-Herzegovina in the 1990s to prevent atrocities. And Nato allies, including the UK, closed the airspace over northern Iraq to protect the Kurds.”

Stoltenberg said he had told Zelensky: “I understand why you’re asking for this. But it will not happen, because if Nato is going to close the airspace of Ukraine, the first thing we have to do is take out Russian air defence systems in Belarus and Russia, as we cannot fly in over Ukrainian airspace with Russian air defence missiles targeting Nato planes.

“And if there is a Russian plane or helicopter in the air, we have to shoot it down and then we are in full war between Nato and Russia. And we’re not willing to do that.

“As Biden, who was US president at the time, put it, we will not risk a third world war for Ukraine.”

President Zelensky visiting the Nato headquarters in October 2023

OLIVIER MATTHYS/EPA

He added: “I remember it was extremely painful to end that phone call [with Zelensky], knowing that his life was in danger.”

Stoltenberg, 66, led Nato for ten years from 2014, during one of the most testing times in its history.

He faced the alliance’s biggest humiliation, losing to the Taliban in Afghanistan, and Europe’s first major land conflict since the Second World War.

Had Nato provided more military support to Ukraine when Vladimir Putin annexed Crimea, he said, Russia’s full-scale invasion eight years later could have been prevented.

Declining to provide Zelensky with air power was part of what Stoltenberg described as Nato’s “contradictory” approach to helping Ukraine.

“On the morning of the 24th of February when the full-scale invasion happened, all nations met at Nato headquarters and we made two decisions,” he said. “One was to step up our support for Ukraine, as we did. The other was to do what we could to prevent this war from escalating beyond Ukraine and become a full-scale war between Russia and Nato.

Russian tanks advancing in the Kyiv region in March 2022

RUSSIAN DEFENCE MINISTRY/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

“Of course, there is an element of contradiction in those two goals because if the only aim was to ensure that Ukraine prevailed, then we could have sent in Nato troops and air forces and fought on the battlefield. We didn’t do that because we didn’t want a full-scale war between Russia and Nato. So we sent weapons and ammunition.”

Stoltenberg, who was born in Oslo, has twice served as Norway’s prime minister and is now the country’s minister of finance.

He compared the situation to the United States’ support for the United Kingdom at the start of the Second World War. “The [US] didn’t want to be involved themselves,” he said. “So they provided weapons but not troops. It was only after Pearl Harbor that the US actually joined.

• Russia pounds Ukrainian power plants with drones and missiles

“Our aim is not to have a Pearl Harbor and end up in a situation where the whole Nato alliance is involved. So we continue to support Ukraine and have enabled them to really fight back, but we are not willing to send in Nato troops and be directly involved in the military conflict with Russia. And I continue to believe that’s the right approach.”

However, he admitted help had been “too little, too late”. “Ukraine demonstrates both the strength and the weakness of Nato,” he said. “Nato allies have, since the full-scale invasion, provided unprecedented military support … without which Ukraine would most likely not have been able to defend itself as they have.

“On the other hand, we have to admit that our support came too late and too little because from 2014, when Russia illegally annexed Crimea and went into eastern Donbas; and until the full-scale invasion in 2022, Nato allies provided hardly any military support, or far too little, and hardly any lethal aid because we were afraid it would provoke Russia to invade. But Russia did invade.

“Had we provided more military support to Ukraine earlier, it could have prevented a full-scale invasion because President Putin may have concluded it was impossible to invade Ukraine, because Nato allies had armed it. But we didn’t do that and therefore it was much easier for Russia to invade.”

Putin may also have been encouraged by the fall of Kabul to the Taliban in 2021, which Stoltenberg admitted was “Nato’s biggest defeat”. He writes about it emotionally in his new memoir, On My Watch, in which he recalls Afghanistan’s vice-president telling him: “You failed us.”

Afghans try to reach foreign soldiers to show their credentials to flee the country outside Kabul airport in August 2021

AKHTER GULFAM/EPA

Stoltenberg added: “We all would like to see a free, democratic Afghanistan, but the reality is that we were not willing to pay the price for Nato allies to ensure that to happen. I think what we learnt over those 20 years is that to build a free and democratic society using military force, as we tried, was just too difficult and too ambitious.”

Though he admitted it had been “painful’ to see girls barred from attending high school, he insisted that pulling the troops out had been the right decision. “It’s Nato’s biggest defeat. But I continue to believe that even though it was painful and many people suffer, it was the right thing to do to leave Afghanistan.”

It was not just external threats he had to deal with. When President Trump took office for the first time, Stoltenberg feared the alliance might collapse. “At the Nato summit in 2018, where President Trump actually said that he was considering leaving the alliance, I was concerned that I was going to be the secretary-general who oversaw the end of Nato.

Stoltenberg meeting President Trump at the White House in 2018

SAUL LOEB/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

“Then we were able to find a compromise — European allies promised to step up to do more and they have actually done more, and that has kept the alliance together. Most are now paying much more than just a few years ago and there are plans to further increase defence spending.”

• Niall Ferguson: German rearmament is far too slow — here’s how to take it to warp speed

Stoltenberg is a great believer of the importance of face-to-face diplomacy, having grown up with his politician father hosting freedom fighters such as Nelson Mandela at their kitchen table for breakfast.

He believes it is crucial to step up support for Ukraine on the battlefield to force Russia to the negotiating table. “I don’t think we can change Putin’s mind,” he said. “He wants to control Ukraine. But I do think we can change Putin’s calculus.

“If the price he pays for that is too high, then he may be willing to sit down. Zelensky has offered talks. He’s said he’s willing to accept a ceasefire. So far Putin has rejected those offers.

“He continues the war because he believes that they can gain more on the battlefield than around the negotiating table. We need to change that calculus, and the only way to change it is to provide military support to Ukraine and make it stronger on the battlefield.”

Stoltenberg with Zelensky in Kyiv

ALAMY

• The conscripts preparing to resist Russia on Finland’s frigid border

Stoltenberg refused to be drawn on whether Norway’s trillion-dollar sovereign fund, the world’s largest, would act as a guarantor for the EU to provide a €100 billion war loan to Ukraine, an idea that has been discussed in the country’s parliament and endorsed by four out of its nine political parties.

“What matters, for me, is that Norway is providing now more support than we have ever done before to Ukraine,” he said.

Since taking office as finance minister in February, Stoltenberg has overseen the tripling of Norway’s military support.

“We are now providing €7 billion in direct financial support to Ukraine, most of it military,” he said. “No other country provides more. Measured against GDP or per capita, and even in absolute terms, Norway — with just five million people — is among the top providers. My responsibility is to make sure Norway continues to be on the top when it comes to providing support to Ukraine, however we do that.”

Though he insisted it was “only Ukraine that can decide what concessions it is willing to give to obtain peace”, he said he had discussed with Zelensky the so-called Finnish solution, a reference to Finland giving up 10 per cent of its territory to Stalin to end the Winter War in 1940.

“At the end of the day, it has to be Ukraine that decides whether they will accept something like Finland was forced to accept,” he said. “Our task is not to give advice to Ukraine. Our task is to provide support to Ukraine.”