WANA (Nov 09) – The news seemed simple at first glance, yet beneath it lay something far beyond agricultural rivalry:

Saudi Arabia has officially registered the Damask rose under the name “Taif Rose” as a global heritage brand.

At the same time, Turkey is seeking to register its Damask rose extract as “Isparta Rose Essence” with the European Union.

And Iran — the very birthplace of the Damask rose, cultivated for over a thousand years in Qamsar, Meymand, and Niasar — still lacks any formal international registration.

The announcement came from Rastegar, head of Iran’s Rose and Rosewater Museum, whose key statement sparked a wave of reactions: “The Damask rose is Iran’s national flower; it was born from this soil and spread from here to the Ottoman Empire, Syria, and then Europe.”

WANA (May 23) – When the name “Rosewater” is mentioned, the mind instinctively drifts to Persia—a land that has simmered its roses in copper cauldrons to extract the pure essence of softness and healing from their petals for centuries. Rosewater has found its place everywhere from the luxury kitchens of Paris to beauty salons […]

But what he described was more than a story about a flower — it was about the gradual loss of Iran’s soft heritage.

The fragrance that once traveled from Kashan to the Kaaba is now being rebranded from Taif to Isparta.

Qamsar — A Fragrance Once Bound for Mecca

For Iranians, the Damask rose is not merely a plant; it is part of their collective memory.

Qamsar, a town in Kashan County, Isfahan Province, lies on the slopes of Mount Karkas and is known as the capital of rosewater in Iran.

Every May, thousands of visitors travel to Qamsar to take part in its traditional rosewater distillation festival.

Kashan, a historic city on the edge of Iran’s central desert, is one of the country’s oldest centers of architecture, handicrafts, and rosewater production.

Each spring, Qamsar’s air fills with the scent of roses as workers, from dawn till dusk, boil the petals in copper cauldrons to produce golâb — the pure essence of the Damask rose.

Unique Chemical Compound Found in Tehran University Rose Study. Social media/ WANA News Agency

For centuries, this same rosewater has been sent to wash the Kaaba in Mecca — a tradition dating back to the Safavid era (16th century) and still observed today.

Mecca, in western Saudi Arabia, is Islam’s holiest city and the destination of millions of pilgrims each year.

Historical sources such as Nasir Khusraw’s Travelogue and Habib al-Siyar note that Kashan’s rosewater held an esteemed place not only in religious rituals but also in Persian medicine and diplomacy. During the Qajar era (19th century), rosewater from Kashan was exported in decorative inlaid containers to the Ottoman Empire, India, and Europe.

Nearby Meymand and Niasar, with their mountainous climates and abundant springs, have long been key centers of rose cultivation. Their rosewater festivals coincide with Qamsar’s, together shaping the cultural identity of the Kashan region.

As a University of Tehran study once put it: “The Damask rose was Iran’s first product to combine economic, ritual, and aesthetic value — much like tea for China or olive oil for Greece.”

The Lost Fragrance of Iran’s Soft Power

But this is no longer just about history. Today, the Damask rose has become a field of soft geopolitical competition.

With brands like “Isparta Rose” and “Taif Rose,” Turkey and Saudi Arabia are not only capturing the global fragrance market — they are also claiming the right to narrate its story.

In other words, when the world speaks of the Damask rose, it now remembers Taif, not Qamsar.

Isparta, in southwestern Turkey’s Mediterranean region, is a cool, mountainous area known as the “city of roses.”

Iran, meanwhile, cultivates 30,000 hectares of Damask roses and produces about 90,000 tons annually — the largest volume in the world.

Yet its share in the global essential oil market remains below 10%. Why?

Because what Iran produces, others brand.

In the language of cultural economics, this is called a “loss of narrative sovereignty” — a country that owns the product but not its story.

WANA (Nov 01) – Researchers at Tehran University have identified a previously unknown chemical compound in rose petals, paving the way for potential new medicinal and nutritional applications. The study, conducted by the Faculty of Science, examined eight native Iranian rose species. Using advanced laboratory techniques, the team identified 81 chemical compounds, including one […]

When Saudi Arabia Enters the Rose Arena

The registration of “Taif Rose” by Saudi Arabia was not merely an agricultural move.

Taif, located in the mountains near Mecca, is a city with a mild climate and lush gardens — now promoted as both a tourism and perfume-production hub through major state investment.

According to the Saudi Ministry of Tourism (2024), “The Taif Rose is part of the Kingdom’s new spiritual and economic heritage.”

In other words, the Damask rose has become to 21st-century Saudi Arabia what oil was in the 20th: a tool for defining a new Saudi identity.

The initiative is part of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s “Vision 2030” plan to transform Saudi Arabia from a purely religious state into one with a global cultural identity.

In this vision, owning symbols such as Arabic coffee, traditional dress, and now the Damask rose serves as both cultural branding and soft power projection — particularly in competition with Iran and Turkey.

Iran’s Missed Opportunity in Heritage Registration

By contrast, Iran has yet to secure UNESCO recognition for the Damask rose itself — only the Qamsar rosewater distillation ceremony is registered as a national intangible heritage, not the product.

As cultural heritage researcher Dr. Mehdi Sotoudeh notes: “Iran has the strongest historical claim to the Damask rose, yet the weakest legal and branding presence among its competitors.”

This reflects a broader gap between Iran’s cultural identity and its modern cultural governance.

Iran has preserved its heritage — but ceded its narrative to others.

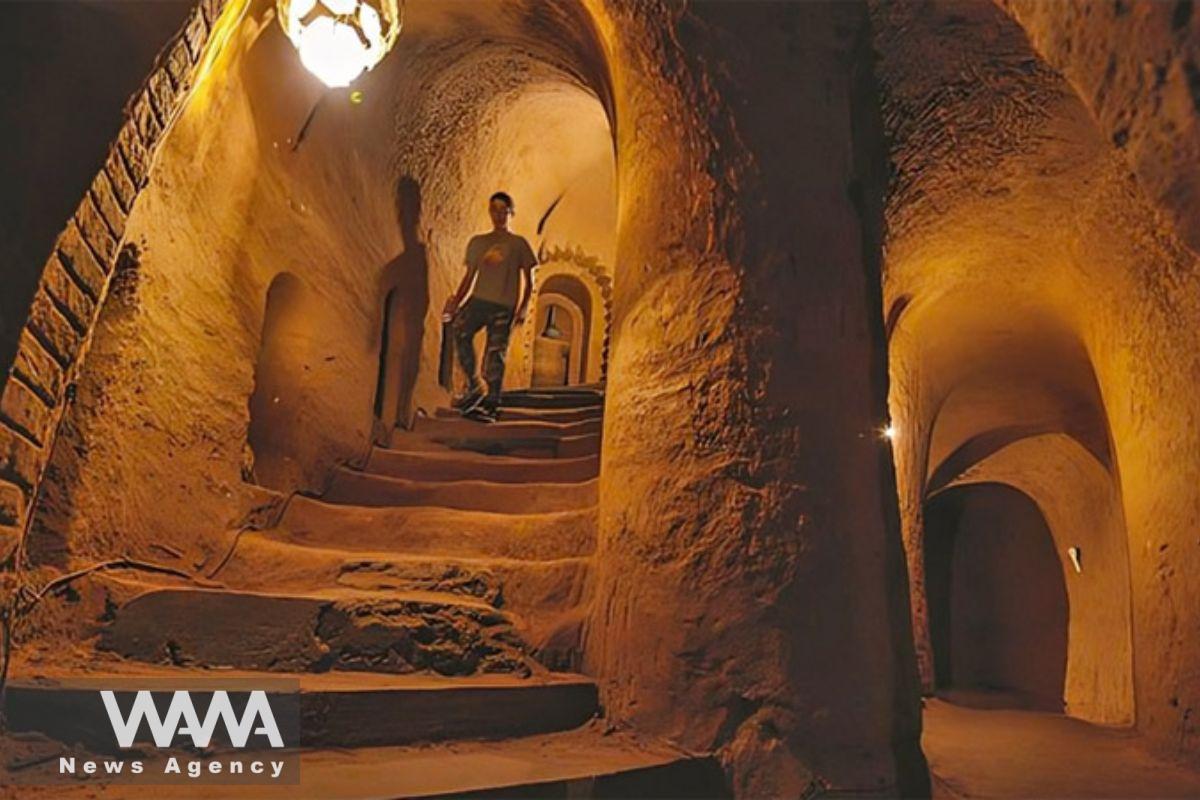

WANA (Aug 21) – Imagine, in the heart of a quiet and silent desert, enemies have attacked the city. Horsemen, with bare swords and fire in their hands, enter the narrow alleys. The houses smell of food, the stoves are still hot, the lamps are lit—yet not a single human being is seen. A […]

A Fragrance Still Iranian — But for How Long?

For Iran, the Damask rose is more than an agricultural commodity; it is a cultural signature — a fragrance woven into Hafez’s poetry, Persian architecture, and traditional medicine.

Yet unless Iran acts swiftly to secure its global registration, it may face the same fate that befell Tabriz carpets and Khorasan saffron.

The Tabriz carpet, from East Azerbaijan Province, is among the world’s oldest and most renowned handwoven rugs — crafted in the mountainous city of Tabriz, at the foot of Mount Sahand.

An Iranian woman weaves a carpet during the 30th Handmade Carpet Exhibition in Tehran, Iran August 26, 2023. Majid Asgaripour/WANA (West Asia News Agency)

Khorasan saffron, from northeastern Iran’s sun-drenched plains, is famed for its vivid color and fragrance, commanding nearly 90% of the global saffron market.

Still, both have suffered from weak international registration, allowing Spain, the UAE, and others to market them under non-Iranian names.

What lies behind the Damask rose controversy, then, is a symbolic struggle over ownership of meaning.

Cultural heritage has become a tool of soft power; names no longer just mark geography — they carry narratives.

And in the global memory, whoever tells the story first, stays.

Qamsar, Niasar, and Kashan still preserve the rose’s true fragrance — but with Saudi Arabia’s “Taif Rose” and Turkey’s “Isparta Essence” now officially recognized, a part of this symbolic heritage battle is already being lost.

The registration of the Damask rose is not merely an agricultural case — it is a test of whether Iran can elevate its heritage from ritual tradition to cultural diplomacy.