While the world remains focused on resolving armed conflicts, another, perhaps even more serious, threat is rapidly unfolding: parts of Eurasia are losing their water sources.

Recently, Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian delivered alarming news during a working trip to the western city of Sanandaj. He warned that if the country’s prolonged drought continues to worsen, Iran may be forced to relocate its capital. Tehran, he said, could become uninhabitable due to the inability to provide residents with sufficient drinking water.

According to Etemad newspaper, Pezeshkian spoke about a critical water supply situation caused by years of drought. “Iran is facing natural challenges — a lack of rainfall and the depletion of water resources — that could have severe consequences. If it does not rain soon, starting next month we will have to impose strict water restrictions in Tehran. And if there is still no rainfall, our reserves will run out, and we will be forced to begin evacuating the city,” the president said.

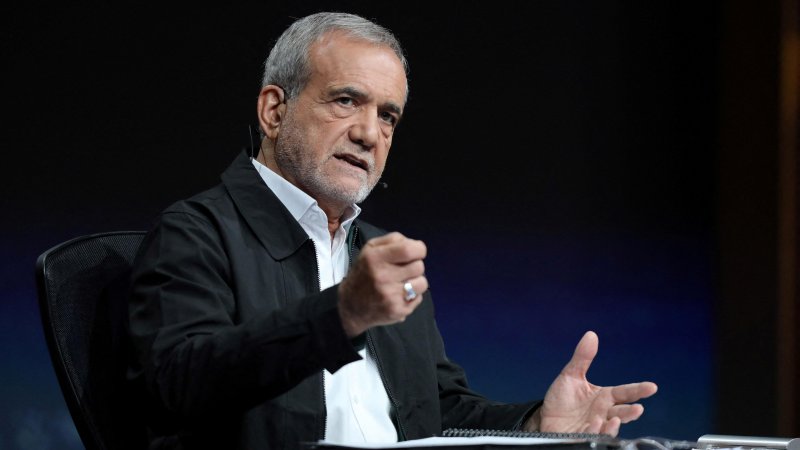

Iranian President Masoud Pezeshkian. BBC

Media reports indicate that over the past five years, Iran has seen a steady decline in precipitation. In 2025, which is nearing its end, Tehran received 40 percent less rainfall than the seasonal average. Spring and summer rains were nearly absent, leading to a catastrophic drop in reservoir levels. Experts are especially alarmed that the drought has affected not only surface water but also underground aquifers.

In July, Tehran’s Water Authority officially warned that reservoir reserves had reached their lowest level in a century. As a result, water was periodically shut off in the capital during summer months to conserve supplies. Both Iranian and international experts have cautioned that only a few weeks remain before Tehran’s taps could run dry.

Water pressure has already been reduced in about 80 percent of households, leaving residents on upper floors of apartment buildings completely without water. Tanker trucks have been delivering water to the city, but supplies are critically insufficient for a metropolis of 13 million people. Authorities even considered declaring a non-working week to encourage residents to leave the capital and reduce pressure on water resources.

Tehran’s water supply comes from five major reservoirs: Lar, Mamlu, Amir Kabir, Taleqan, and Latian.

Climatologists attribute the crisis to a drought that has gripped Iran for five consecutive years, accompanied by record-breaking summer heat. Yet experts say climate is not the only factor; over-extraction of groundwater, inefficient agriculture, and rapid urbanization have also contributed to the disaster.

Hopes were pinned on autumn rains, but the situation has not improved. On November 3, Behzad Parsa, Director General of Tehran’s Water Supply Authority, announced that the remaining reserves would last only about two weeks.

Analysts in Iran and abroad note that the construction of numerous dams, intended to alleviate water shortages, has proven ineffective amid ongoing droughts and, in some cases, has worsened the problem. As surface water sources dried up, rising consumption due to population and industrial growth further depleted underground reserves.

The water shortage now threatens not only the country’s food security but also its energy sector. Environmental consequences are already visible in the form of increased atmospheric dust.

The water crisis is also heightening social tensions and may lead to protests, as seen in Khuzestan Province in 2021 and 2022. Aware of the threat, the government is searching for solutions. Appeals to conserve water are not enough, so authorities are exploring desalination projects using seawater from the Gulf of Oman and transporting it to industrial regions in central Iran.

Although the catastrophe of Lake Urmia is not directly related to Tehran’s water supply, the disappearance of what was once the second-largest saltwater lake in the world — after the Caspian Sea — illustrates the scale of Iran’s environmental crisis. Due to drought and extreme temperatures, the lake has almost completely evaporated, leaving behind a salt-covered desert.

A study published in the Journal of Arid Land found that excessive groundwater extraction was the key factor behind the disappearance of the lake, similar to cases across the Northern Hemisphere. Experts writing in Environmental Development and Soil Security added that dam construction and soil salinization also accelerated its drying.

Lake Urmia. Getty Images

Water scarcity is not limited to Iran. Türkiye and other parts of the Middle East are also facing similar challenges. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan recently admitted that Ankara, Bursa, and Istanbul are already experiencing water shortages, though he blamed opposition-led municipalities that govern these cities.

Environmental experts warn that by 2030, the entire region might face a severe water crisis. According to Türkiye’s meteorological service, the country has recorded the lowest precipitation levels in 52 years, with rainfall in the Mediterranean region down by 31 percent.

Specialists say the only way forward is to identify and develop new water sources.

Meanwhile, northern countries are also beginning to worry about access to drinking water. Environmentalists believe that the shortage of fresh water will eventually become a global problem — one the entire planet will have to confront.

By Tural Heybatov