Subscribe now for full access and no adverts

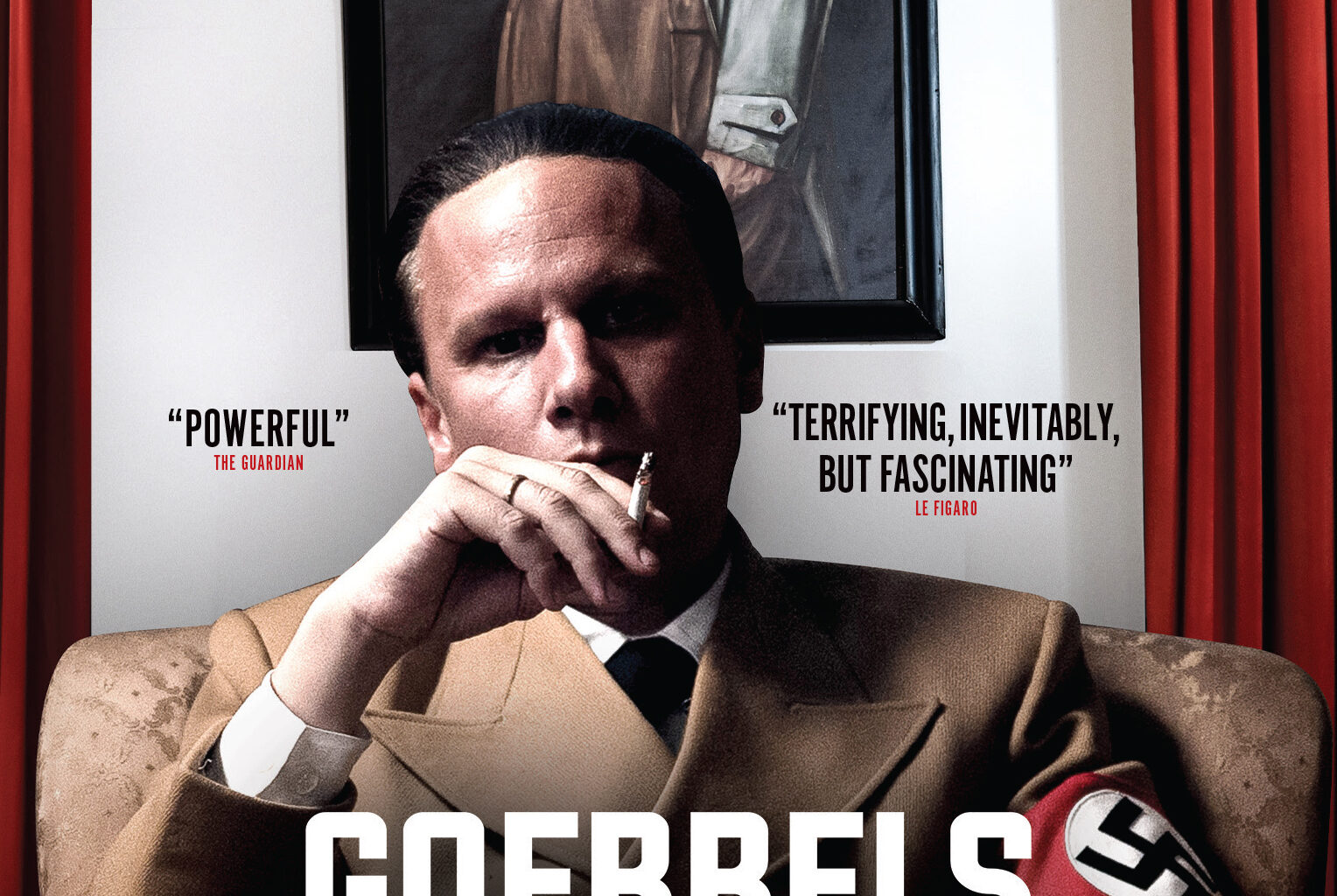

Goebbels and the Führer is a recent German feature film that explores the intense relationship between Hitler and the man he called his Hexenmeister (‘sorcerer’), his Propaganda Minister. It shows how Goebbels created an image of Hitler that promoted him to almost god-like status and ensured that at every major occasion he was surrounded by cheering, adoring crowds. The movie also acts as a warning to a new generation of Germans, ending with a quote from Primo Levi, a survivor of Auschwitz: ‘It happened… and it can therefore happen again. Therein lies the core of what we have to say.’

Such a message might have seemed excessive a few years ago. But with the far-right Alternative for Germany party (the AfD) accused of openly aping elements of Nazi ideology, or adapting them to the 21st century (for instance, by replacing anti-Semitism with Islamophobia), this warning seems more relevant. The AfD is now one of the largest parties in the Bundestag and is represented in nearly every state across Germany. Apparently, screenings of Goebbels and the Führer in Germany have been met with stunned silence as cinema audiences take in the message that is hammered at them.

stephan pick

stephan pickThe movie was written and directed by Joachim Lang, who is perhaps best known for his 2018 film Mack the Knife, centred around Berthold Brecht’s The Threepenny Opera. However, it is two of Lang’s other past productions that particularly inspired his new film. One was a documentary-drama he wrote about the anti-Semitic Nazi propaganda film Jud Süss. The second was a documentary he produced about the German actor Heinrich George, who appeared in the vast, delusional epic Kolberg, which Goebbels had made at the end of the war, depicting the heroic defence of German forces against Napoleon’s troops. Huge resources of men and materials went into the production of Kolberg, just as the Reich was crumbling. Both films are referenced in this new project, which was released in UK and US cinemas earlier this year.

Everyone knows the story of how the Third Reich ended in the ruins of a devastated Berlin. So, in a long pre-title sequence, Lang chooses to open his film in the final days of the Nazi regime. Mixing actors in the drama with authentic black-and-white archival film, Goebbels is in a screening room watching newsreel coverage of what turns out to be Hitler’s last appearance on film. He comes briefly out of the Berlin bunker to decorate a group of boys from the Hitler Youth who have all bravely resisted the Russian advance. As the camera captures Hitler’s hand quivering behind his back, Goebbels erupts and says this must not be included in the public newsreel release. His aide argues, ‘But the Führer is only a shadow of his former self and this is a true record’. ‘I decide what is Truth,’ shouts Goebbels. ‘Truth is what is good for the German people.’ Indeed, this sums up the central thesis of the film. Goebbels will decide what the German nation will see and hear, and he will present an image of the Führer that inspired and led Germany for 12 years. Later, Goebbels says, ‘I created the myth of the Führer.’ Talking with his wife Magda, he tells his aides, ‘My wife and children and I will set an example for posterity, what it means to be loyal’. And, of course, it all ends in the ashes of the Führerbunker.

stephan pick

stephan pick‘Uncle Führer’

Soon after Hitler came to power in 1933, Joseph Goebbels was appointed Minister of Propaganda. He quickly took control of all media in Germany, including the press, radio, and cinema. Goebbels and Hitler were film enthusiasts, and Hitler regularly had a film screened for him and his guests of an evening. From the beginning, the role of the cinema in influencing and forming public opinion in Germany was emphasised. ‘We are convinced’, Goebbels wrote, ‘that films constitute one of the most modern and scientific means of influencing the masses.’ Through film, Goebbels would control the image of Hitler that was seen in Germany and abroad.

The core narrative of Goebbels and the Führer begins in March 1938 with the Anschluss, or annexation of Austria into the Third Reich. Goebbels sends trainloads of loyal supporters along with vast numbers of flags and banners to Vienna to ensure that the images recorded will show Hitler receiving a fantastic reception. When the Führer addresses the people from a balcony overlooking the Heldenplatz in Vienna, crowds pack the square. The black-and-white images of the real thing are stunning. ‘Propaganda is like a painting,’ Goebbels tells his aides. ‘The most valuable painting is not the one most resembling reality but the one which best triggers the emotions. We will create images that will endure.’

stephan pick

stephan pickThis is repeated when Hitler returns to Berlin. A public holiday is declared. Schools and shops are closed. It is made clear that all loyal Berliners must be out on the streets to welcome Hitler back to his capital. Everything is prepared down to the finest detail. An SS officer rehearses holding up a little girl who hands the Führer a bouquet of flowers as he passes in his motorcade, and we see this for real in the black-and-white footage of the event.

In his personal life, Goebbels was known to be a serial womaniser, although he was married to Magda and they had six children. Hitler frequently visits the family and the poor kids – the girls all dressed in pretty white dresses with bows in their hair – line up and address him as ‘Uncle Führer’. The film shows Goebbels seducing a Czech singer, Lída Baarová, who becomes his mistress. He tells her he loves her more than any other woman he has ever known. But his philandering eventually catches up with him. After producing another child, Magda confronts him and says she wants a divorce. The other Nazi leaders are shocked not only by his ‘skirt chasing’ but also by the fact that he is going out with, of all people, a Czech, a ‘lowly Slav’. Hitler is told and intervenes. He calls Magda and Goebbels to meet him. He announces that Goebbels must stop seeing Baarová as a scandal will rock the party. He tells Magda there is to be no more talk of divorce. The couple must stay together for the good of the regime. They are forced to sign an agreement confirming this, in front of Hitler. ‘What are mere individuals compared to the fate of nations?’ Hitler tells the couple. It is a powerful scene, cleverly nuanced and well performed.

stephan pick

stephan pickRobert Stadlober plays Goebbels. Although not a lookalike, he gives a dramatic and convincing performance as the preening and self-important Propaganda Minister. His performance strengthens as the war years go by and, when giving his ranting anti-Semitic speeches, Stadlober is at his terrifying best. Franziska Weisz plays Magda with about as much dignity as such a dreadful figure can attract. She is a beauty in her youth, but ages during the film until taking on a haunted look by the time the narrative reaches 1945.

Sadly, Fritz Karl does not impress as Hitler. It’s an impossibly difficult role to portray on film. Just as with Winston Churchill, there have been fine portrayals and dire characterisations. Karl is too tall and striking to be Hitler. He is also too measured, too calm, too reasonable to convince as the Führer. No doubt much of this is down to Lang as writer and director. He is quoted as saying, ‘Showing all these figures as screaming brawlers doesn’t show why our parents and grandparents fell for them.’ That’s a fair point and no doubt the contrast Lang wanted to convey was that between the all-powerful leader who demanded total unity and obedience, and the more humble individual behind this. But, if that was the intention, I’m afraid it doesn’t work. Goebbels and the Führer is substantially weakened by having an unconvincing Führer.

stephan pick

stephan pickGoebbels’ Propaganda Ministry

The Propaganda Ministry became a central element of Nazi rule. It had sections that controlled the press and German radio. A core part of its operation was the Reich Film Association (Reichsfilmkammer). Only members of the different branches of the Association (producers, directors, writers, cameramen, and so on) were allowed to work in the German film industry. All manuscripts and scenarios for production had to be approved, and without authorisation from the Association it was impossible to produce films. All Jews were excluded, as were all other political dissidents and anyone thought to be hostile to the regime. Although most films during the Third Reich were not overtly concerned with politics, censorship and control of the cinema was a cornerstone of the Nazi propaganda effort. By 1934, 14,000 people were employed in the myriad state and Party bodies concerned with control of the cinema industry. In 1935, the Reich spent more than 40 million Reichsmarks on theatre and cinema productions, a huge investment in culture. Few regimes in history have curtailed and controlled artistic freedom so totally, and yet used the cinema as a weapon of propaganda so effectively.

Rallying the nation

The film fast-tracks through the late 1930s. In September 1938, the Munich Agreement infuriates Hitler and Goebbels. The surrender of the Sudetenland by Chamberlain and Daladier prevents the Nazis from having the war they desired. However, it is clear that the German people are relieved and do not want war. It is Goebbels’ task to prepare the nation for this eventuality.

When war does come in September 1939, Goebbels commissions two films to stir up anti-Semitism among the people. Veit Harlan is told to make a film, Jud Süss, about an 18th-century Jewish financier at the court of Württemberg who is eventually blamed for fraud and treason. He is tried in a kangaroo court and although there is no evidence against him, he is sentenced to death. Harlan initially resists the offer of making the film. But Goebbels makes it clear that everyone is a soldier now the country is at war. ‘And you know what happens when soldiers disobey orders,’ he says.

A documentary also released in 1940 was Der ewige Jude (‘The Eternal Jew’), directed by Fritz Hippler. Using grotesque parodies of Jewish life shot in some of the ghettoes in Poland, these two productions are usually seen as the most horrific examples of anti-Semitism on film. Both were made on the direct orders of Goebbels, whose extreme Jewish hatred is a strong theme in Goebbels and the Führer.

Bundesarchiv Hitler greets Goebbels’ daughter Helga, while her father watches.

Bundesarchiv Hitler greets Goebbels’ daughter Helga, while her father watches.After the Battle of Stalingrad turns the course of the war on the Eastern Front, Goebbels enters his most manic phase. ‘I’ll transform this catastrophe into a huge rallying cry for the war,’ he declares. He stages a giant rally at the Sportpalast in Berlin, where he whips the crowd into a frenzy calling for ‘Total War’ as a means of overcoming the military strength of their enemies through the force of will. Actual footage of the rally is intercut with Goebbels rehearsing for his big speech. It is one of the best sequences in the movie.

As the war continues, the Nazi leaders savour their policy of exterminating the Jews. Dreadful but authentic archive footage of shootings and executions is shown. SS Chief Heinrich Himmler announces this is ‘a glorious chapter in our history’. These sequences are presented as a clear warning from history to young Germans today.

After the Bomb Plot of July 1944, Goebbels visits a visibly shaken Hitler. But he soon comes to think that his survival is a sign he must continue to victory. ‘Destiny has confirmed my mission,’ Hitler tells Goebbels. Together they watch footage of the perpetrators of the Bomb Plot being brutally executed. Hitler actually ordered that these executions should be filmed. Fortunately, the footage has never been found, so in the movie we simply see Hitler and Goebbels as they are watching what must have been hideous scenes of torture and death.

Goebbels, becoming increasingly deranged, declares he will make an epic out of an event in the Napoleonic wars, called Kolberg. This will show the German people how victory can still come out of adversity and will help lift the mood of the people. ‘A good mood wins wars,’ says Goebbels. Huge resources are allocated to making the film. Soldiers were transferred from the Front to act as extras. Kolberg epitomises the madness that overtook the Nazi leadership in the last months of the war.

The final scenes in the Führerbunker in Berlin are a reprise of the movie’s opening. Realising all is lost, Goebbels and Magda agree to commit suicide. Believing there is no future for their children in a Germany without National Socialism, they poison their six children first and then, on the day following Hitler’s suicide, they kill themselves. On that same day, 1 May 1945, US troops are liberating Dachau concentration camp. The world will soon realise the extent of the horrors committed by the Nazis.

Bundesarchiv Goebbels delivers his speech at the Berlin Sportpalast on 18 February 1943. Whipping the crowd into a frenzy, the Propaganda Minister called for ‘Total War’ to overcome Germany’s enemies.

Bundesarchiv Goebbels delivers his speech at the Berlin Sportpalast on 18 February 1943. Whipping the crowd into a frenzy, the Propaganda Minister called for ‘Total War’ to overcome Germany’s enemies.A powerful warning

The script of Goebbels and the Führer is crude and clunky in places. There are too many declarations – ‘now we are making history’ – in case the viewer hasn’t quite kept up with the significance of events. And it’s difficult to take seriously a scene in which, after admiring Goebbels’ new baby, Hitler quietly sits down on the couch and tells his Propaganda Minister, ‘Oh I have some news. I’ve decided to invade Russia’!

Goebbels and the Führer does not compare well with other German movies that have covered some of the same ground. Downfall (2004, directed by Oliver Hirschbiegel) depicted the final days of Hitler in the Berlin bunker in April 1945. By focusing on life inside the crazed Führerbunker, it is far more intense, and Bruno Ganz gave a performance as Hitler that was both stunning and terrifying. This was a man who even in his final days you would not want to cross. For me, Ganz gives the finest depiction of Hitler on the screen. And, although different again, The Zone of Interest (2023, directed by Jonathan Glazer) provided a more chilling vision of the consequences of Nazi anti-Semitism, even though not a single dead body is ever shown.

However, for a young audience not aware of all the stories told and the propaganda depicted, Goebbels and the Führer will no doubt have a powerful impact. Its combination of constructed drama with authentic black-and-white footage is extremely effective, and its depiction of the appalling anti-Semitism of the Nazi regime will probably be a revelation, and definitely a warning, to many.

Goebbels and the Führer (2024)

Written and directed by Joachim Lang.

Starring Robert Stadlober, Fritz Karl, and Franziska Weisz.

A Zeitsprung Pictures cinema production.

Available now on Blu-ray, DVD, and on multiple streaming services including Amazon Prime and Apple TV.

Images: Deutsches Bundesarchiv