Pakistan is scaling back its dependence on imported LNG as volatile global prices and a weakened currency strain its economy. The government is deferring gas deliveries and turning instead to coal, hydropower, and nuclear energy to stabilize supply and reduce import costs. Cheaper coal and expanding hydro and nuclear capacity, much of it financed by China, are reshaping the country’s power mix. Yet persistent debt, rigid contracts, and grid inefficiencies keep electricity among the most expensive in South Asia.

Pakistan’s main buyer of LNG, the state-owned Pakistan LNG Limited (PLL) has been quietly renegotiating LNG delivery schedules, deferring several cargoes planned for 2026, and seeking additional postponements as spot prices remain volatile. The country’s long-term LNG portfolio – currently dominated by long-term contracts with QatarGas (3.8 million t/y, 2016–2031), Italy’s Eni (0.8 million t/y, 2017–2032) and Azerbaijan’s Socar (0.8 million t/y, 2023–2028) – has become a liability as Brent-linked formulas sent import bills soaring in rupee terms. Government subsidies that once shielded consumers became fiscally unsustainable, while currency depreciation worsens the pain. Although Pakistan was careful not to link its binding commitments to spot JKM prices (which are currently $3/mmBtu higher than Brent-linked prices), and recent decline in oil prices has eased contract costs slightly, LNG in absolute terms remains far more expensive than when Pakistan signed its 15-year deals with Qatar.

After intensive talks that started in August, the PLL reached an agreement with QatarEnergy and Eni in October to defer up to two LNG cargoes per month in 2026. The arrangement is currently confirmed only for the next year, with future deferrals to be reviewed in line with Pakistan’s evolving gas balance. Meanwhile, the Azerbaijan supply deal—originally set to expire at the end of 2025—was extended to 2028. Unlike the Qatari and Italian contracts, it offers greater flexibility, allowing Pakistan to receive one cargo per month at a price below prevailing market rates, with no penalties foreseen in case PLL forgoes its right of purchase.

Related: Oil Prices Sink 4% as OPEC Moves to Balanced 2026 Outlook

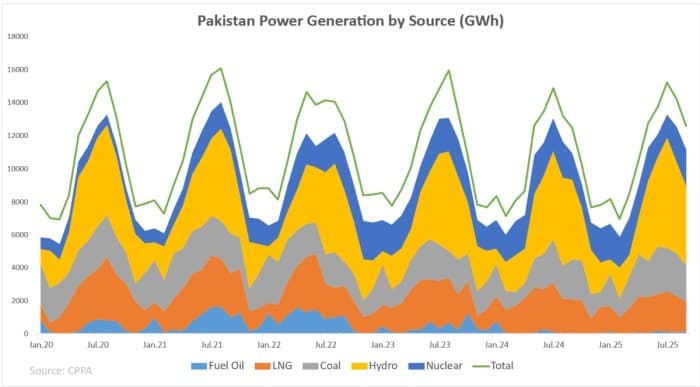

Only a few years ago, Pakistan was a fast-growing buyer of liquefied gas, becoming one of the key drivers of spot-market demand in South Asia. Today, it is pulling back. Petroleum Minister Ali Pervaiz Malik has publicly blamed the country’s heavy reliance on LNG imports for stagnant domestic gas exploration. The guaranteed operation of regasified LNG (RLNG) plants inhibits local production and forces state buyers to absorb expensive contractual volumes even when demand is weak. According to data from the Central Power Purchasing Agency (CPPA), the share of LNG-fired power generation has fallen from 20% in 1Q 2024 to 14% in 3Q 2025, as the government prioritizes coal-based and renewable sources (mainly hydropower) to reduce import exposure. Yet transmission bottlenecks between Pakistan’s northern and southern grids often compel operators to run RLNG plants first, even when cheaper alternatives exist, locking the system into inefficiency.

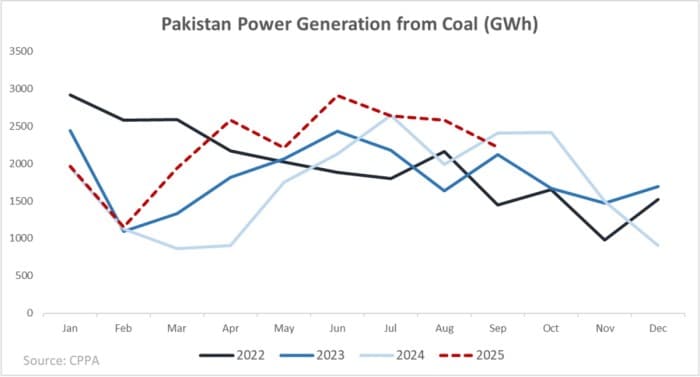

Coal and hydropower have emerged as the main alternatives. With international coal prices collapsing from an average of $400/t in 2022 to around $100/t in the first nine months of 2025, Pakistan has quietly increased coal’s role in its generation mix. Imported coal’s share rose from 25% to 27% in first 10 months of 2025, with about 70 % of total coal consumption now directed to power plants. The government has also encouraged greater use of domestic reserves, reducing reliance on imports from 60% in 2020 to roughly 25% in 2024. Most imported coal still arrives from South Africa (50-55%) and Indonesia (20%), but local output – particularly from Sindh Province’s vast deposits – is becoming increasingly significant. Pakistan’s recoverable coal reserves exceed 186 billion tonnes, 99% of which lie in Sindh Province, where the Sindh Engro Coal Mining Company (SECMC) operates mines producing about 7 million tonnes annually. Although domestic coal is lower grade in comparison with South African or Indonesian alternatives, its average price of $90-95/t makes it cheaper than imported fuel, reinforcing coal’s appeal as a base-load source.

Hydropower has strengthened even faster. According to the Pakistan Electricity Review 2025, hydropower’s share of generation climbed to 30% in 2024 and continued rising into 2025, when June output peaked at an all-time monthly high of 6,670 GWh – about 44% of that month’s total electricity supply. Seasonal volatility remains an obstacle, but water-based generation seems to have become a critical buffer against imported-fuel shocks.

Nuclear energy, meanwhile, is expanding steadily. The nuclear sector’s share in Pakistan’s power mix has tripled from 8% in 2020 to 27% in 2025, generating roughly 2,227 GWh in January 2025. Pakistan now operates 6 commercial reactors at its Karachi and Chashma sites, with a combined capacity of 3.3 GW, all built by China National Nuclear Corporation. Construction of the seventh Chashma-5 reactor (1,200 MW capacity) began in December 2024, a $3.5 billion project under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), underscoring Beijing’s pivotal role in the country’s energy transition.

The economics behind this transformation remain fragile. Power generation costs are rising as imported fuels and the rupee’s depreciation inflate electricity prices. According to the International Energy Agency, Pakistan’s energy-price component climbed from $39 to $55/MWh between 2019-20 and 2024-25, while the capacity-price element declined from $37 to $25/MWh. The shift reflects rising fuel prices, which even in the face of stable or even declining power plant operational costs still lift the consumer electricity prices. Indeed, residential tariffs followed the pattern: from roughly PKR 25/ kWh ($0.09) in 2023, they increased to PKR 35–40 ($0.12–0.14) in 2024 before easing slightly in 2025 as fuel prices stabilized. Despite this moderation, Pakistan’s power remains among the most expensive in the region, with persistent capacity payments still eroding fiscal space.

Behind these numbers lies a deeper structural constraint. Pakistan’s energy infrastructure is financed overwhelmingly by external debt — particularly loans from the IMF, the Asian Development Bank, and China. Many of the large power plants and transmission lines built under CPEC operate on take-or-pay or capacity-payment terms, obliging Islamabad to pay for output even when demand falls. Roughly 20-30 % of the country’s external debt is now owed to Chinese creditors, a burden exacerbated by dollar-linked tariffs and costly project guarantees. Without successive IMF bailouts, Pakistan would likely have defaulted several times in recent years. The paradox of its energy economy is that while state-owned power companies generate profits, those gains are consumed by compensation payments to private operators and by the inefficiencies of a grid unable to dispatch power from cheaper plants when transmission limits intervene.

Pakistan’s pivot away from LNG marks a pragmatic, if uneasy, adaptation to global price realities. Coal, hydropower, and nuclear energy are filling the gap, but each brings its own vulnerabilities — from environmental costs and water dependence to long construction cycles and heavy debt. The country’s next energy crisis may not be about scarcity, but about affordability: whether its evolving mix can deliver reliable power without deepening a financial strain already at the core of its economy.

By Natalia Katona for Oilprice.com

More Top Reads From Oilprice.com