It was some feat for Donald Trump, a billionaire with his own airliner who lived in an eponymous skyscraper in liberal New York and wintered in a Florida palace, to brand himself as the conservative champion of working Americans.

But his political alchemy on the economy is dissolving.

Trump’s presidency is taking a wobble as he flaunts his sun king’s life of luxury and obsesses over building, literally, his personal legacy with vanity projects like a White House ballroom over his campaign vow to make America affordable again.

Trump is coming across as increasingly oblivious to a wave of economic insecurity sweeping the nation, which is hitting many of the voters he won over in two presidential election victories as he transformed the GOP from its starchy country-club roots to a blue-collar election machine.

In pictures: Trump’s East Wing demolition

It might be a golden age for White House decor, but the new era of prosperity that he promised in 2024 is still elusive.

A slew of recent polling shows deep pessimism among Americans about the current state of the economy and its prospects. But Trump doesn’t want to know. “The economy is my thing. And we have the greatest economy in history,” he told Fox News this week. He seemed irritated to be confronted with questions about high costs for food and housing.

This retreat into a gilded bubble couldn’t come at a worse political moment. His approval ratings are tanking. The Epstein scandal is back to haunt him. And the Beltway political and media world has suddenly discovered the new buzz issue of “affordability” after Democrats won gubernatorial elections in Virginia and New Jersey with populist economic promises.

As he seeks to stave off lame-duck status, Trump desperately needs to rediscover his common economic touch. If he fails, the midterm elections next year could be grim for Republicans.

Trump’s initial electoral edge on the economy was a shrewd mix of branding, a political sixth sense about resentment boiling in hollowed-out industrial heartlands in 2015 and his own mystique as a consummate dealmaker.

Critics in recent days have lampooned his perceived lack of empathy for citizens who are struggling economically. But he was never a Bill Clinton-style “feel your pain” politician. Trump instead amplified the voice of voters who believed they’d paid the price for the globalization and free trade policies that made the establishment elite rich. He might have been wealthy —but he was never in the club. Like his base, he knew what it felt like to be left out: He’d been spurned by high society for decades, deemed vulgar and nouveau riche.

“We’ve made other countries rich while the wealth, strength, and confidence of our country has disappeared over the horizon,” Trump said in his searing first inaugural address in 2017. “One by one, the factories shuttered and left our shores, with not even a thought about the millions upon millions of American workers left behind. The wealth of our middle class has been ripped from their homes and then redistributed across the entire world.”

Trump’s political magic was also cultural. His dystopian tirades on immigration and crime were popular. His vulgarity helped him pose as an outsider. And the Democratic Party’s turn to aspirational upper middle-class voters and apparent disdain for those immortalized in Hillary Clinton’s disastrous “basket of deplorables” comment helped sever it from the working class. Trump’s birtherism campaign against Barack Obama was a way to exploit backlash to the first Black presidency. And a leftward move by Democrats on social issues drove more voters into his camp.

Trump also had something else — a mythology of success. His spell on NBC’s “The Apprentice” evoked the image of a self-made business titan. If he made himself rich, why not everyone else? Trump rally-goers often cited this as a reason to vote for him, even if Trump’s history of business scrapes and near-bankruptcies told a more questionable story about his effectiveness as a tycoon.

In the 2024 campaign, Trump rode the advantage of fond memories of the pre-pandemic economy in his first term. It was also easy to lambaste the Biden administration’s months of denial on inflation and the failure of Democratic nominee Kamala Harris to spell out her own convincing appeal to the middle class. Trump posed in an apron and worked the fry station at a McDonald’s in Pennsylvania, boosting his common-man credentials.

It would not be true to say that Trump has done nothing to tackle costs felt by working Americans. His entire economic policy, including tariff hikes on almost every country in the world, is designed to revive the glory days of the 20th-century factory economy. “If you think about your hometown in the state that you grew up, Main Street looks a lot different today than it did many years ago. And President Trump wants to restore America as a manufacturing superpower around the globe,” White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said in March.

The White House claims the massive tax cuts in Trump’s “one big beautiful bill” put more money in the pockets of most Americans, even if the wealthiest did best. It says its program of gutting regulations and canceling wasteful spending will do the same. Next year, a new portal known as TrumpRx will seek to lower drug prices. Last week, the president announced a deal with two pharma giants to lower the price of obesity drugs. The administration claims tariffs raised trillions of dollars. The stock market has been on a tear.

Evidence is mounting that Trump’s policies are making the affordability crisis worse. His tariffs are raising the price of goods for Americans. He’s had to promise a massive bailout to farmers hammered by his trade war policies. His new brainwave is for $2,000 payments to Americans pulled from government coffers swelled by tariffs. This sounds like a nice idea. But it could backfire by spiking inflation — and it is hardly a long-term answer for millions of Americans juggling bills and cutting back on the basics, who are now also confronting fears that AI will take their jobs.

The administration implicitly acknowledged its policies are making things harder for working Americans when Trump and Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent this week pledged swift tariff relief on some staples like coffee and fruit. “Coffee, we’re going to lower some tariffs. We’re going to have some coffee come in. We’re going to take care of all this stuff very quickly, very easily. It’s surgical. It’s beautiful to watch,” Trump said on Fox.

But he was partly to blame for the spiking price of a cup of joe, having slapped a 50% tariff on major producer Brazil because it prosecuted his friend former President Jair Bolsonaro for election interference. If ever there was a case of a president’s fixations making life worse for his people, this was it.

When all else fails, there’s always denial. Trump suggested on Fox that polls highlighting anxiety over the economy were fake. And on “60 Minutes” this month he said, “We have no inflation” and, “Our groceries are down.”

The inflation rate is 3.0%, far lower than its peaks during the Biden administration. But in the political argument it’s often forgotten that prices aren’t going down; the rate at which they are increasing has simply slowed. It’s an equation every shopper understands, even if the president doesn’t.

The gap between peoples’ experiences of the economy and his sunny diagnosis of the country’s performance is highlighting how Trump, a politician who performs best when he has an enemy to attack, lacks a vocabulary for empathy. He’s a salesman, a booster, or as his critics would say, a con man who thrives on hyperbole.

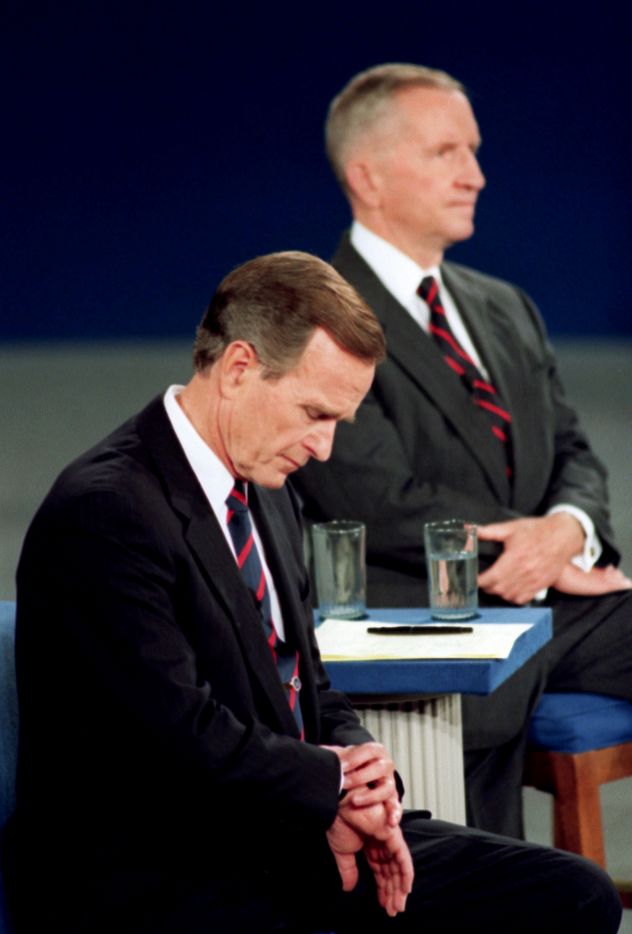

Trump is not alone among presidents in struggling to articulate a positive economic message in tough times. In a 1992 campaign debate, President George H.W. Bush was caught looking at his watch while Clinton connected on voters’ economic struggles, creating an instant metaphor of indifference. During the 2012 campaign, Obama’s advisers struggled to find the balance between celebrating the rebound from the Great Recession without appearing oblivious to the unresolved struggles of many voters who weren’t feeling it.

Trump’s behavior in the government shutdown made his case harder — for instance, when he asked the Supreme Court to stop food stamp payments to more than 40 million Americans, handing Democrats an easy political weapon. And his indifference to rising health insurance premiums doesn’t help much either.

Trump’s advisers know he has a problem. They are considering whether he should tour the country to give economy-focused speeches. This follows calls from some Republicans, like Georgia Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene, for him to drill down on “America First” economic policies after months spent trying to win the Nobel Peace Prize.

“The president gets it. He knows this is an issue,” a senior White House official told CNN’s Alayna Treene. “But he’s frustrated he’s not getting credit for what he’s doing.”

Scheduling Trump for a scripted speech might sound like a good idea. But it could backfire, like the infamous time in the 2024 campaign when he went to North Carolina to engineer an economic pivot and a wild campaign rally broke out. “They wanted to do a speech on the economy so we are doing this as an intellectual speech. You are all intellectuals today,” he told his crowd, mocking his own campaign strategy.

A better option must just be to hold rallies. They might at least restore his political mojo and renew his connection with his voters. Rallies have played an important role for Trump. He used them almost like vast focus groups, testing out lines scanning the crowd to test reactions. He has no such equivalent source of political intelligence in the White House, surrounded by obsequious aides, conservative media and his Cabinet of millionaires and billionaires. Trump does mingle on the patio of his Mar-a-Lago club. But hefty membership fees mean it’s hardly a haunt of working Americans.

Presidents often get too much credit when the economy roars and too little when it sours. But any prolonged downturn in the coming months could doom Republicans in the 2026 midterm elections. And Democratic candidates showed the way for their colleagues in Virginia and New Jersey with blue-collar economic themes and by toning down progressive cultural rhetoric.