Belgium wasn’t always Europe’s drug hub. Today, its ports – Antwerp, Zeebrugge, and their sprawling container terminals – move millions of tonnes of cargo, concealing tonnes of cocaine, heroin, and synthetic drugs. Their deep-water access, nonstop container traffic, and Schengen freedoms make the country a dream for traffickers – and a nightmare for law enforcement.

In Antwerp alone, drug seizures surged from 91 tonnes in 2021 to nearly 110 in 2022, overtaking Rotterdam and cementing the port’s place at the centre of Europe’s narcotics trade.

Just 45 kilometres inland, Brussels now feels the shockwaves – shootings, gang turf wars, and fear spreading through neighbourhoods such as Molenbeek and Anderlecht.

So, after an Antwerp judge – who spent four months in a safe house – warned the country was at risk of becoming a “narco-state,” how real is the threat? The jurist also warned that organised crime is infiltrating ports, police, and even the judiciary, with mafia networks acting as a parallel power. Belgium’s ports remain a critical entry point to Europe, where drugs flow in, and its streets pay the price.

How smuggling works

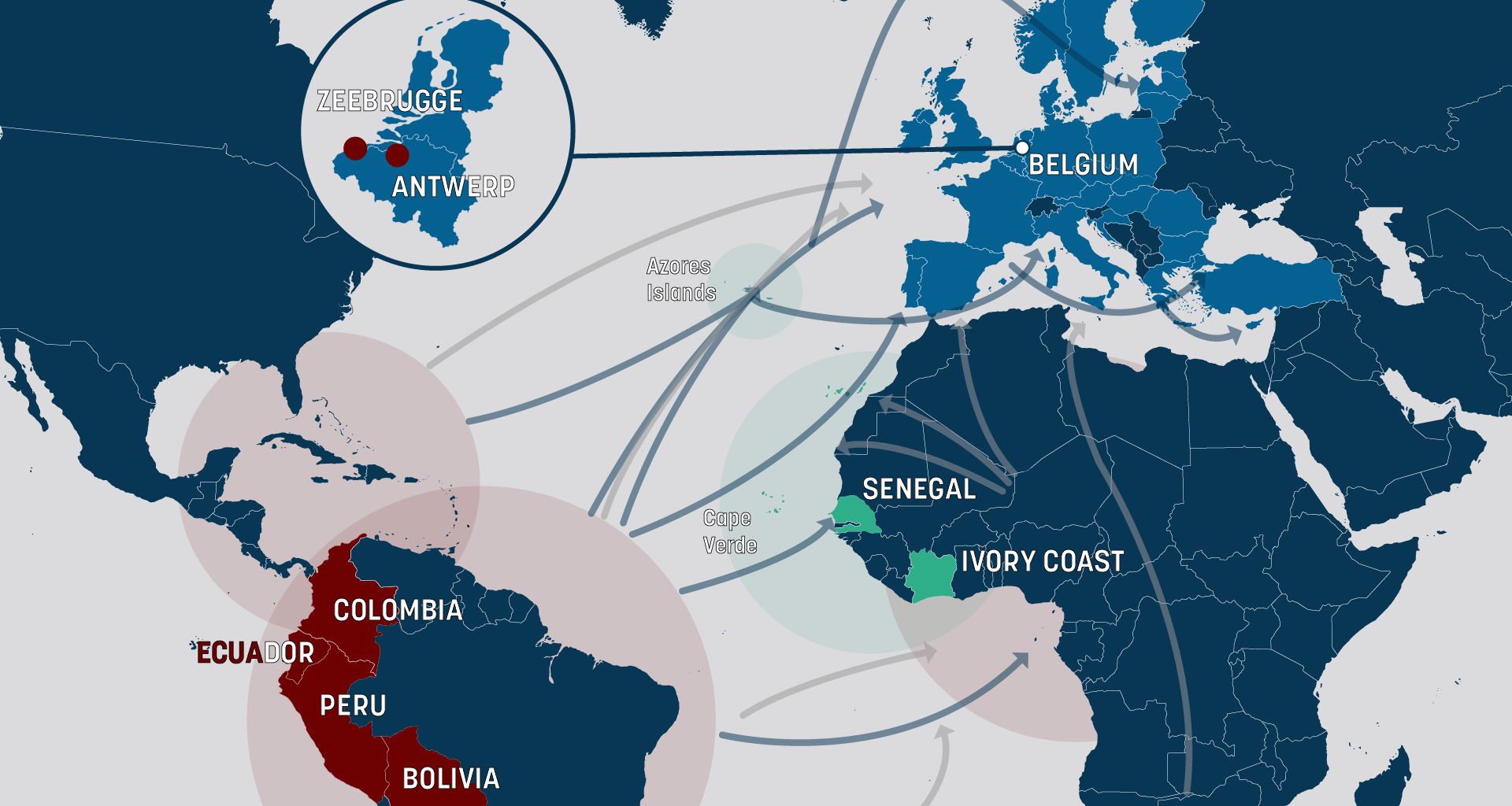

The drug trade starts far from Europe. For cocaine – the most heavily trafficked drug through EU ports – bulk shipments leave Colombia, Peru, or Ecuador, stuffed inside legal cargo like fruit crates, machinery parts, or steel pipes. Some go straight across the Atlantic, while others zigzag through trans-shipment points in West Africa – via Senegal, Ivory Coast, or Cape Verde – or through Caribbean ports to blur their trail.

By the time containers reach Europe, the cargo manifests appear clean. Some pass through the Canary Islands or the Azores, making the paperwork even harder to trace. Then they dock at Antwerp, Zeebrugge, or Rotterdam, where “extractor” crews – often teenage recruits – break open the containers, remove the drugs, reseal them, and slip away before inspectors arrive.

In the numbers game of smuggling, networks have adapted quickly. Belgian customs data now show traffickers favor smaller, more frequent loads to dodge scanners – 82 cocaine shipments intercepted in early 2025 in Antwerp averaged 204 kilogrammes each, down from 359 kilogrammes in 2024.

Europol notes that gangs use feeder ships and container swaps during transit to obscure origin points and exploit weak checks.

The same patterns apply to other drugs. Heroin moves along the Balkan route from Afghanistan via Turkey and the Balkans, while cannabis resin still flows from Morocco into Spain, and synthetic drugs and precursors such as methamphetamine arrive from Asia by air freight or even postal parcels.

All roads lead to Belgium

Geography made Belgium a gateway, but globalisation made it a goldmine. Antwerp’s position, connected by road and rail to every major Western European market, means a large share of the cocaine that lands there is trucked elsewhere – cut, repackaged, and resold at many times the profit.

The scale is staggering. The European cocaine market is estimated at €11.6 billion, while cannabis adds another €12.1 billion. With that kind of money moving through legitimate supply chains, Belgium’s ports have become ideal not only for smuggling but also for money laundering. In 2024, the Antwerp region alone recorded 128 drug-related arrests, including 16 minors.

But what starts at the docks rarely stays there. Brussels – 45 km away inland – is now on the front line of the drug fallout. At a press conference in July 2025, prosecutors reported 57 shootings – 20 of them over the summer – many tied to turf wars between rival gangs, according to Brussels’ public prosecutor Julien Moinil.

In February, a gunfight outside Clémenceau metro in Anderlecht left one dead. In September, a massive police sweep checked 708 people and 621 vehicles across the city. Yet the violence never stops. Brussels now records a homicide rate of 3.19 per 100,000 people – among the highest in the EU’s major urban areas – with neighbourhoods like Molenbeek and Anderlecht hit hardest.

A fight that just started

Across the EU, overall drug seizures have climbed over the past decade, with the amounts of amphetamine, meth, and ecstasy fluctuating year to year. Every catch is a reminder of what still slips through. Belgian customs estimate they intercept only 10–40% of cocaine arriving at its ports. The rest floods Europe. A kilo bought for a few thousand euros in Latin America can fetch close to €30,000 on EU markets, warns the European Union Drugs Agency (EUDA).

The money doesn’t just disappear; it’s washed through trading firms, real estate, and logistics companies that double as laundering fronts operating in Belgium. Even with 16.7 tonnes of cocaine seized in Antwerp in the first half of 2025, traffickers are outpacing enforcement: hiding shipments behind encrypted networks, corrupt dockers, and shell firms.

Brussels is racing to catch up. The EU’s new Roadmap Against Drug Trafficking targets chemical precursors, widening controls to cover fast-evolving derivatives. The EUDA now backs the Commission on monitoring and threat assessments – completing the EU’s first-ever precursor risk reviews in early 2025. As for the city, other ideas come to mind: merging Brussels’ six police zones and increasing spot raids.

But as prosecutor Julien Moinil warns: “Ten or twenty years of laxity can’t be fixed overnight.”

Belgium remains Europe’s gateway: seizures make headlines, but the real trade never stops.

(aw, cm)