Over the past several months, I have written articles about the economies of individual EU member states as well as about the state of the euro zone and EU economies as a whole. Overall, my message has been on the negative side; with a series of recent economic news updates from Eurostat showing a mixed picture of strong and weak growth, high and low unemployment, etc., the time is right to put a finger on the pulse of the European economy.

I will do so using four variables: GDP growth, unemployment, budget balances, and inflation. Taken as ‘snapshots,’ these variables can tell us a great deal about where a country is economically.

Let us begin with real annual GDP growth. As Figure 1 reports, the picture is mixed, with five countries above 3% and 14 countries below 1%.* In Germany, Finland, and Luxembourg, the economy actually contracted in the second quarter:

Figure 1

Source: Eurostat

Source: Eurostat

It is concerning that 17 of the EU’s 27 member states did not reach 2% real GDP growth. Although this is only a one-quarter snapshot of their economies, it is worth keeping in mind that the 2% growth rate is a minimum for any country that wants to maintain its standard of living over the longer term. The fact that a majority of EU’s member states are struggling to get to that level, or falling well below it, suggests that Europe may be on a path to industrial poverty.

To this point, the 27 EU member states mustered an average annual GDP growth rate of 1.4% in the second quarter; the euro zone fared even worse at 1.3%.

The big question for the faster-growing economies is how much substance there is behind their growth rate. Normally, I would answer this question by going back in time to look at the length of their growth streak and compare national accounts figures, such as consumption and investment. However, there is another way to highlight the solidity of an economy, namely, to examine the state of variables that signal strength or weakness from other viewpoints in the economy.

One such variable is unemployment. Figure 2 has the numbers from the third quarter—one quarter after the growth rates in Figure 1. The one-quarter difference is perfect for our purpose: if the GDP growth rates of the countries at the top in Figure 1 were actually solid (and not a temporary ‘surge’ in the midst of an otherwise depressing trend), the third-quarter unemployment figures should look good. The opposite obviously applies for the low-growth economies:

Figure 2

Source: Eurostat

Source: Eurostat

The five countries with a GDP growth rate above 3% were Cyprus, Croatia, Bulgaria, Lithuania, and Poland. In terms of unemployment, though, they are all over the place: while the jobless rate is low in Poland (3.2%) and Bulgaria (3.6%), it is moderately high in Croatia (4.7%) and Cyprus (5.0%). Lithuania has the biggest troubles of this group with its 7% jobless rate.

These unemployment numbers tell us that the good GDP growth numbers for Poland and Bulgaria exhibit underlying strength in the economy. By contrast, Lithuania is sailing into an economic headwind; its 3.2% GDP figure is not a signal of strength and resiliency. That could change, though, if the growth rate is sustained and unemployment comes down 2-2.5 percentage points.

At the other end of the growth spectrum, the three economies with a shrinking GDP in the second quarter are also spread out in terms of unemployment. Luxembourg is right on the edge of the economic trouble zone: it couples its -0.4% decline in GDP with 6.7% unemployment.

The other two shrinking-GDP countries, Finland and Germany, are two diametrically opposed cases: while the Finnish jobless rate was 9.9% in the third quarter, the German equivalent was only 3.8%.

This means that Finland, of course, is in serious macroeconomic trouble—and there is more bad news coming for them. Before we get there, though, a word of caution regarding Germany. Their combination of negative GDP growth and a stunningly low unemployment rate of 3.8% is a macroeconomic oxymoron. Given the structural problems that the German economy is burdened by, I can only conclude that they will not work themselves back to Europe’s lowest unemployment rate; if I were a betting man—which I am not—I would put my money on their jobless rate climbing to the 4.5-5% range over the winter months.

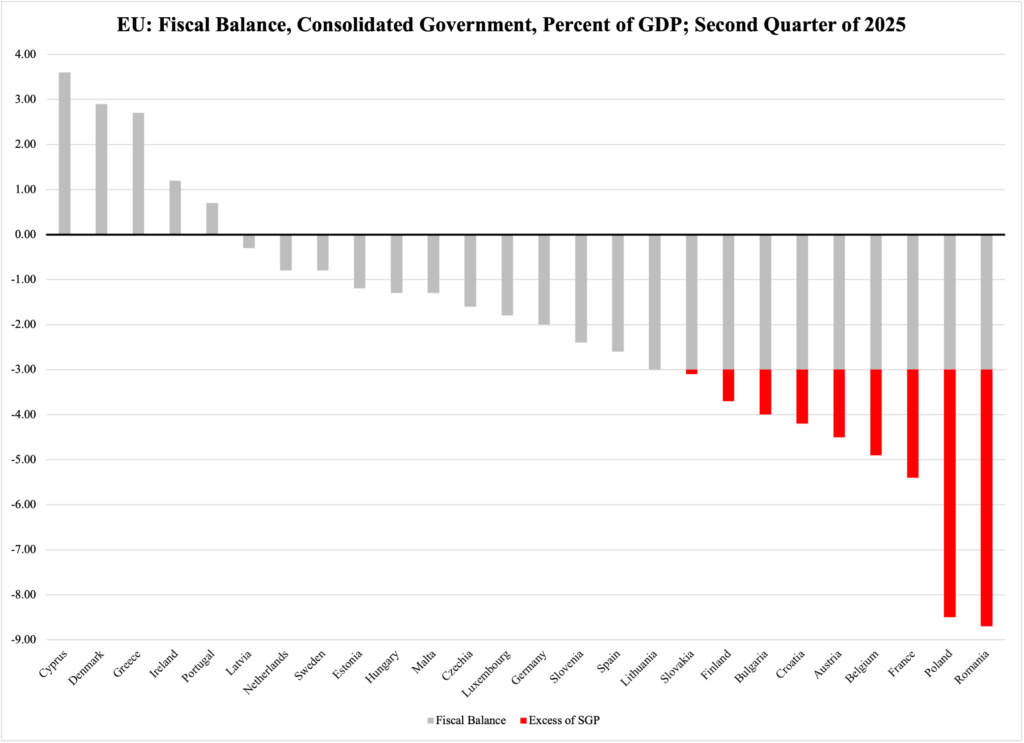

Another important but often overlooked economic indicator is the fiscal status of the consolidated government sector (which consists of all levels of government, including national, regional, and local).

As Figure 3 explains, most of the EU’s member states have deficits in their government finances. The numbers, which are from the second quarter (Eurostat is painfully slow in publishing this type of data), reinforce the good news for some countries—and the bad news for others.

Figure 3

Source: Eurostat

Source: Eurostat

Cyprus, the GDP growth leader, also has the strongest public finances. Together with a moderate unemployment rate, this suggests that the Cypriot economy is on solid footing: it is generating more than enough tax revenue to pay for its government, and we can expect their unemployment rate to nudge downward over the coming months.

While having nearly the same unemployment rate as Cyprus, Croatia—another strongly growing economy—is struggling to feed its public sector. The second quarter came with a 4.2%-of-GDP deficit for its consolidated government. From a macroeconomic viewpoint, this does not have to be a problem for Croatia—an interim deficit is never a problem—but since the fiscal shortfall exceeds the EU’s statutory 3% limit, we should expect fiscal tightening by the Croatian government.

It is possible that Croatia’s respectable 3.6% GDP growth figure has deep macroeconomic roots; an unemployment rate of 4.7% does not dispute that possibility. However, if this is the case, the fiscal deficit becomes an alarming signal of a major structural deficit in the Croatian public finances.

If, on the other hand, the growth rate is an uncharacteristic spurt, the 4.2% deficit must be an indicator of more trouble to come. Can we expect the same political battle over deteriorating government finances in Zagreb as we have already seen in Paris, Berlin, Bratislava, The Hague, and other European capitals?

Last but not least, a word about inflation. Its figures can tell us something about where an economy is heading, but since inflation is fundamentally a monetary phenomenon, it is often more or less decoupled from real sector economic performance. If anything, the causality tends to run from inflation to the real sector: when inflation goes up, it weakens economic confidence. Businesses and households become less inclined to spend money.

The opposite applies when inflation comes down, though the causality is not symmetric; it takes longer for people to respond to good economic news—lower inflation included—than to bad economic news.

With this in mind, Table 1 should give us pause. It reports the year-to-year inflation figures for the three months of the third quarter. The numbers highlighted indicate the highest inflation rate for the quarter. In two-thirds of the EU’s member states, the highest inflation rate showed up in September.

Table 1

Source: Eurostat

Source: Eurostat

Here again, our growth ‘heroes,’ Cyprus and Croatia, are in very different situations. While Cyprus enjoys price stability—unheard of for an economy growing at 3.6% per annum—the Croatian inflation rate of 4.6% is a red flag that calls for urgent policy response.

The problem for Croatia is that they cannot tighten monetary policy; their monetary authority sits in Frankfurt, Germany, and has bigger fish to fry than Croatia. The small Balkan state will have to make do with whatever policy crumbs the ECB can send her way.

Another country that stands out is Germany. Its inflation rate rose steadily through the third quarter—while the German economy was shrinking. This is not supposed to happen; the last thing Germany needs now is a slide into anything resembling stagflation, but that seems to be where they are heading.

Overall, the European economy is not in good shape. Based primarily on the problematic inflation trend and secondarily on poor public finances, I would expect many countries to move in a more austere fiscal direction in the coming months. This will have a dampening effect on overall economic activity, which in turn comes with higher unemployment and another round of weak fiscal numbers.

This is not the only scenario for Europe going into 2026, but until clear indicators show otherwise, it is the most likely one.

—

*) Ireland is excluded due in large part to their extreme swings in business investments. Those swings distort the statistics and frankly make Ireland look like a ‘freak economy.’