During the autumn school break, I visited my homeland, the Háromszék region in Transylvania, with my family, where I held three book presentations and signing events about my interview series Being Hungarian in America, written during the past three years we spent in the United States (New Jersey). Although it was I who initiated these events at the libraries of Sepsiszentgyörgy, Csíkszereda, and Barót, I was wondering how interested the local audience would be in the stories of Hungarians living in the North American diaspora. The vivid interest and thoughtful questions came as a pleasant surprise.

The first book presentation took place at the Bod Péter County Library in Sepsiszentgyörgy (Sfântu Gheorghe), a place I used to frequent as a student, but where I hadn’t been for 30+ years…That morning, during my pre-event site visit, I stood somewhat anxious at the door of the so-called Blue Room, wondering whether the large and empty hall would be filled by the evening. I also pondered whether my enthusiasm for the topic and the routine I had gained from my approximately 50 book presentations and signing events across North America would be enough to spark genuine interest among the Transylvanian Hungarians living 9,000 kilometers away from the U.S.

The room didn’t completely fill up in the evening, but many people did come—among them old schoolmates and their parents still living in the area, acquaintances, and also strangers interested in the topic or generally the events offered by the library. This, in itself, was already a great honor and a source of joy for me.

At the request of library director Szabolcs Szonda, I first spoke about myself—how I experienced the cultural shock caused by moving from Transylvania to Hungary, why I stayed there after university, and how we started our family in Budapest with my husband, whom I met there. My earlier plans to move back home thus dissolved, yet since then, I have felt at home in both countries. After that, we discussed why I moved with my family to America in 2022, and how we have become active members of the local Hungarian communities (in Passaic/Garfield, New Brunswick, and New York). I also spoke about why we regularly visited Hungarian events along the East Coast and even in more distant states and Washington, D.C.—how we lived an active Hungarian diaspora life.

At the book presentation held at the Bod Péter County Library in Sepsiszentgyörgy (Sfântu Gheorghe) PHOTO: Bod Péter County Library

Afterwards, I mentioned that even though I had gone there as a mother and wife, I soon began to work as a journalist, and I conducted my first interview with the Hungarian parish priest of Passaic, NJ. For me, that interview offered a first glimpse into a very interesting kind of Hungarian world that had been completely unknown to me until then. Together with my slowly accumulating personal experiences, it seemed to be a professionally fascinating, distinctive hidden world that deserved to be explored in depth. Following that first interview, more than a hundred further interviews were completed, along with about the same number of reports and surveys about the lives of Hungarians active in the North American communities—about their personal and family life, community habits, and organizations.

I explained that in these diaspora life stories, I didn’t primarily intend to present adventurous individual immigrant stories, but rather to depict the life of the communities themselves, as well as the motivations behind individual activities—why some, in addition to their paid jobs and family responsibilities, dedicate so much of their time to voluntary work for the survival of local (and sometimes larger, diaspora-level) Hungarian communities. I highlighted that this voluntary work today still requires serious personal sacrifice, since the old Hungarian neighborhoods—where earlier immigrants could get by even without speaking English—have disappeared. Nowadays, it may take several hours of travel for someone to take their children to the nearest weekend Hungarian school, scout troop, folk dance group, or church, or to participate in other Hungarian community events. Even though staying connected with the homeland and loved ones back home is much easier now than before the regime change of 1989–90 in Hungary, being Hungarian in America still comes with many new challenges.

I told the audience that as a journalist, I was also interested in the similar difficulties faced by various Hungarian families, communities and organizations (for example, demographic, political, economic, social, and cultural changes; the inevitable generational shift due to the aging of the founding generations; the re-evaluation of voluntary work and personal relationships; the involvement of youth; the increasing rate of mixed-language marriages)—and in how they attempt to remedy these (for example, through various scholarship programs and awards recognizing voluntary service, reaching out to youth with voluntary work not necessarily requiring Hungarian language skills, and fostering closer cooperation between individuals, generations, and communities).

‘I was also interested in the similar difficulties faced by various Hungarian families, communities and organizations…and in how they attempt to remedy these’

I also informed the audience that these interviews, conducted with North American Hungarians committed to their language, culture, traditions, and local communities, were published in Hungarian newspapers with the explicit purpose of familiarizing readers in Hungary and the Carpathian Basin with the everyday struggles of their compatriots living in the diaspora. These articles aimed to show their conscious and often self-sacrificing voluntary work for the survival of Hungarian identity, the exemplary lives they lead, and the lessons that can be learned from them. By presenting a cross-section of the contemporary Hungarian diaspora in America, I sought to offer readers a glimpse into its likely future as well.

I explained that these interviews were also published in book format—altogether five volumes—under the titles Magyarnak lenni Amerikában I, II, and III, and Being Hungarian in America I and II, published by Bocskai Rádió in Cleveland, OH. While the first Hungarian-language volume, coming out in December 2023, mostly mapped the communities around our Northeast (New Jersey) home, the second volume, released in August 2024, broadened both geographically and organizationally the range of interviewees. The third volume, published in March 2025, included several people dear to me who had been left out of the earlier volumes, as well as others through whom (either personally or virtually) I reached out to in regions and states less populated by Hungarians—such as Arizona, North and South Carolina, and Texas.

Although the 106 interviewees living in 18 U.S. states and in Canada offer a wide diversity in terms of gender, age, profession, and residence, they share a common trait: all are Hungarians committed to their local diaspora communities. They nurture, preserve, and pass on the Hungarian language, culture, and traditions not only within their families but also through voluntary work linked to local weekend Hungarian schools, scout troops, churches, folk dance and other cultural groups, and civil organizations.

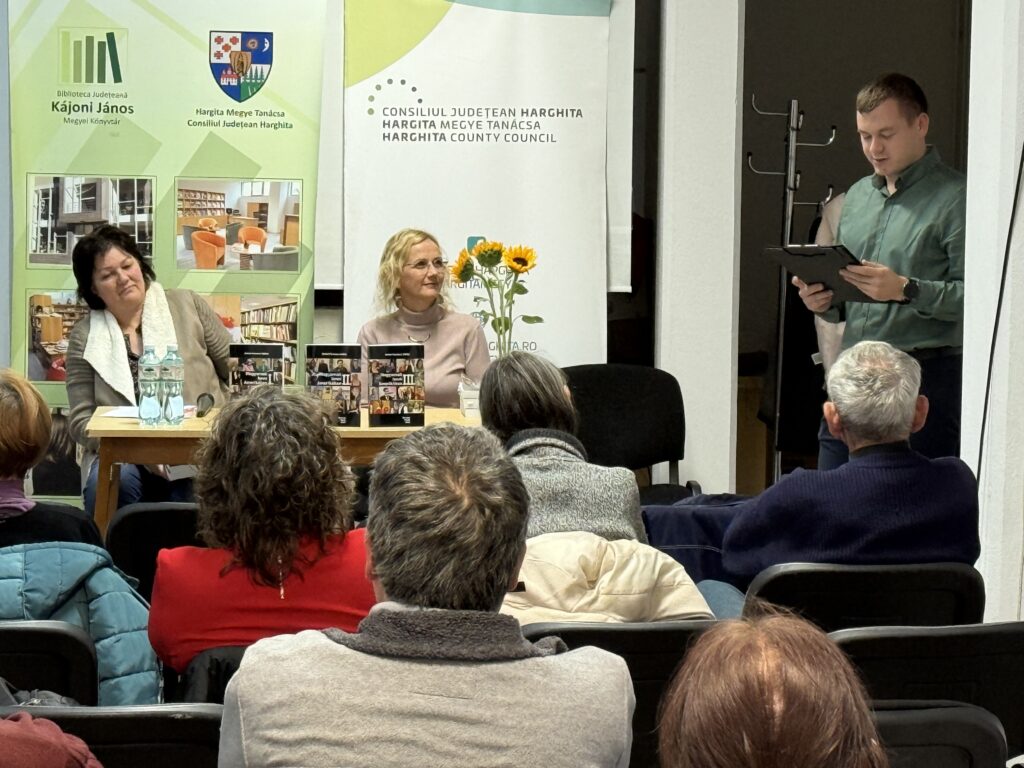

At the book presentation held at the János Kájoni County Library in Csíkszereda (Miercurea Ciuc) PHOTO: courtesy of Ildikó Antal-Ferencz

At the book presentation held at the János Kájoni County Library in Csíkszereda (Miercurea Ciuc) PHOTO: courtesy of Ildikó Antal-Ferencz

The first and third volumes focus primarily on local community members and leaders, while the second introduces mainly leaders of local and diaspora-level organizations (such as the American Hungarian Federation, the Hungarian American Coalition, the Hungarian Scout Association in Exteris (KMCSSZ), the American Hungarian Schools’ Association (AMIT), the Hungarian Diaspora Council, etc.). Yet, each volume also includes individuals active in the fields of science, art, media, and business, as well as honorary consuls and young people who have participated in various scholarship programs (of the Kőrösi Csoma Sándor Program, Diaspora Higher Education, Hungary Foundation, Balassi Institute, Reconnect Hungary, etc.).

Moreover, the two English-language compilations make these distinctive stories of the better-known and lesser-known key figures and communities of the North American Hungarian diaspora accessible to an even wider audience. I revealed that I have managed to ‘map’ only about half of the U.S. states so there is another half to go, and that a new element of my interest has become the group of Americans who may not speak Hungarian, but who have Hungarian roots and wish to contribute to the preservation of Hungarian culture. I also mentioned my growing desire to explore Hungarian communities in South America and Australia—so there is plenty of work ahead of me, and until a greater task finds me, I intend to continue conducting diaspora interviews.

Although the history of Hungarians living in the Carpathian Basin has obviously been shaped by different events—they still live in their homeland, i.e., they didn’t immigrate—yet, in certain respects, minority existence raises similar, ever-present as well as new questions and challenges. My audiences responded with understanding, since they themselves face many comparable difficulties: significant demographic and cultural changes, mixed-language marriages, decline in the number of church-goers, the passivity of youth, etc. At the same time, they listened with fascination to the kinds of challenges they encounter far less—at least in the Háromszék region—such as weekend Hungarian schools; scouting and folk-dance groups as the exclusive forms of youth organization; the mass closure of Hungarian churches; the aging of the founding generations without successors; etc.

During the discussion, I often quoted from my interviews—mainly from those made with people with Transylvanian origins, as well as with some refugees of the 1956 revolution and freedom fight, given the late October timing of the events. I also quoted one interview in particular about being a Hungarian from Transylvania and living in America from Zsolt Jakabffy, a pastor in Los Angeles, which was very well received at all three locations—besides the above-mentioned library, at the János Kájoni County Library in Csíkszereda (Miercurea Ciuc), and at the Líviusz Gyulai Library in Barót (Baraolt):

‘People often ask me, was I homesick? Do I regret it? I’ve lost many dear old friends, and, more importantly, I’ve lost many years of my parents’ old age, some of which I could have spent close to them. Yet, God still gave me the chance to be with my mother in her final days. I regret the loss, but I can understand why, as a pastor from Transylvania, I found myself in a context that is similar to the one I left: a foreign language environment where Hungarian identity and heritage must be preserved. In Mezőtelki, which is a village with a mixed ethnic population but with a Romanian majority, we ran a Hungarian kindergarten—this is how we tried to keep the Hungarian identity there, continuing the work of our predecessors. Here, we are doing the same, but in a much larger geographical dispersion, almost the size of Hungary. We are trying to pass on what God has entrusted to us: faith, language, culture, and nationality. Over the past 20 years, quite a few pastors have left after two or three years; they couldn’t cope with it. To do this service, we need the training that God has given us so far through our lives, enabling Him to use us in the future.’

At the book presentation held at the Líviusz Gyulai Library in Barót (Baraolt) PHOTO: Líviusz Gyulai Library

The discussions unfolded in a similar way at the other two locations, where my partner for the discussion was Bea Tiboldi, the president of the Csíki Mothers’ Association. She mentioned several times how much she appreciated that I often emphasized community and voluntary work as an essential and indispensable means and way of life for nurturing and preserving Hungarian identity (besides and beyond family life). In her view, this is just as important a factor within the Carpathian Basin as it is in the Hungarian diaspora elsewhere.

Many questions from the audience concerned Transylvanian aspects, the general lessons I had learned while in the U.S., and my future plans regarding the books—the most important and urgent of which is the republication of the interviews in Hungary and their presentation there and across the Carpathian Basin. Some questions referred to famous Hungarian American writers such as Albert Wass and István Fekete Jr., and several attendees shared their own family stories connected to America, too.

Yet, the most intriguing question concerned ‘the lost Hungarians’. In my answer, I explained that the Hungarian Communions of Friends, founded more than 50 years ago by András Ludányi and Lajos Élető, and its annual ITT-OTT Conferences were built on a core idea opposite to the previously prevailing ‘emigrant’ mentality. According to the spirit of such diaspora existence, a Hungarian living in America or anywhere in the world remains part of the global Hungarian nation. Thus, from the perspective of the mother country or the Carpathian Basin, such individuals are never lost, as long as they consider themselves Hungarian and actively work for the survival of that identity. Only those Hungarians become truly ‘lost’ to the Hungarian nation who do not consider their Hungarian identity and their rich Hungarian cultural heritage as a value, and make no effort to preserve and pass it on to the next generation.

Related articles: