World War II ended 80 years ago this year, making surviving veterans like Vernon Brantley living history.

“I was born in Sturgis, Kentucky, in 1924, which makes me a little over 100 years old,” he said. He was born during the Great Depression and took ROTC in high school as war raged across the globe. Graduating at 17, he worked in non-essential military jobs before working for Studebaker Aviation in South Bend, Indiana. Studebaker was critical to the war effort, and Brantley was the final test inspector on Wright-Cyclone engines, which powered the B17 Flying Fortress. While his friends were drafted into the military, his essential work allowed him to defer.

But Brantley stepped forward anyway.

“I volunteered, and turned down my deferment,” he said succinctly.

Vernon Brantley. Courtesy photo.

Vernon Brantley. Courtesy photo.

He opted to join the newly formed U.S. Army Air Forces, created in 1941. After basic training in Mississippi, testing in Alabama (where his high score qualified him for the Army Specialized Training Program), and attending the technical skills program in New York before its closure as D-Day approached, Brantley found himself back in Kentucky with the 75th Infantry Regiment.

With all of the high test scores and specialized training, Brantley was finally given a role: Jeep driver. Most jobs in the military don’t clearly define their importance or detail all of the tasks associated with the position, and Brantley proves that fact has nearly always been true.

“They put me in charge of a Jeep, and when you say, ‘you’re just a Jeep driver,’ actually: you are a courier, you are in charge of taking the information from company headquarters to take them to different noncomms and officers,” he chuckled, thinking how his job was not quite as simple as the title implied.

Vernon Brantley, then and now. Courtesy photo.

Vernon Brantley, then and now. Courtesy photo.

Battle of the Bulge

Back in the Bluegrass State and only 14 miles from home, Brantley got engaged to his high-school sweetheart. Six weeks after the wedding, he was en route to join the war in Europe.

“From Camp Breckinridge [Kentucky], we went by train to Camp Shanks in New York, loaded on a troop ship along with thousands of other GIs,” Brantley remembered. “It took us 14 days to cross the Atlantic — at that time, German submarines were making terrible slaughters on the troop ships and supplies that were going over — but we had an uneventful trip… to Liverpool, England. From there by train, [we] went up into Wales, right outside of Swansea, and we picked up our vehicles and ammo and various things like that. [We] lived there until the latter part of October of 1944.”

After convoying to Southampton, the troops boarded a landing craft for their next destination.

“[We] landed at Rouen, France, and assembled our division there. [We] were in the process of moving 15,000 men with all their equipment…to Aachen, Germany where we were supposed to hit the Siegfried Line. That’s when the Battle of the Bulge broke out — Dec. 16. They diverted us from Aachen, and piecemeal, we moved back over in the area around Bastogne and headed off the spearhead of the Wacht am Rhein, which was Hitler’s last big offensive.

“And that’s where we ran into it.”

‘Go like hell’

The fight against the German campaign was brutal. Brantley recalled how the troops took on both enemy and friendly fire, with one Allied aircraft even dropping a 500-pound bomb on the soldiers.

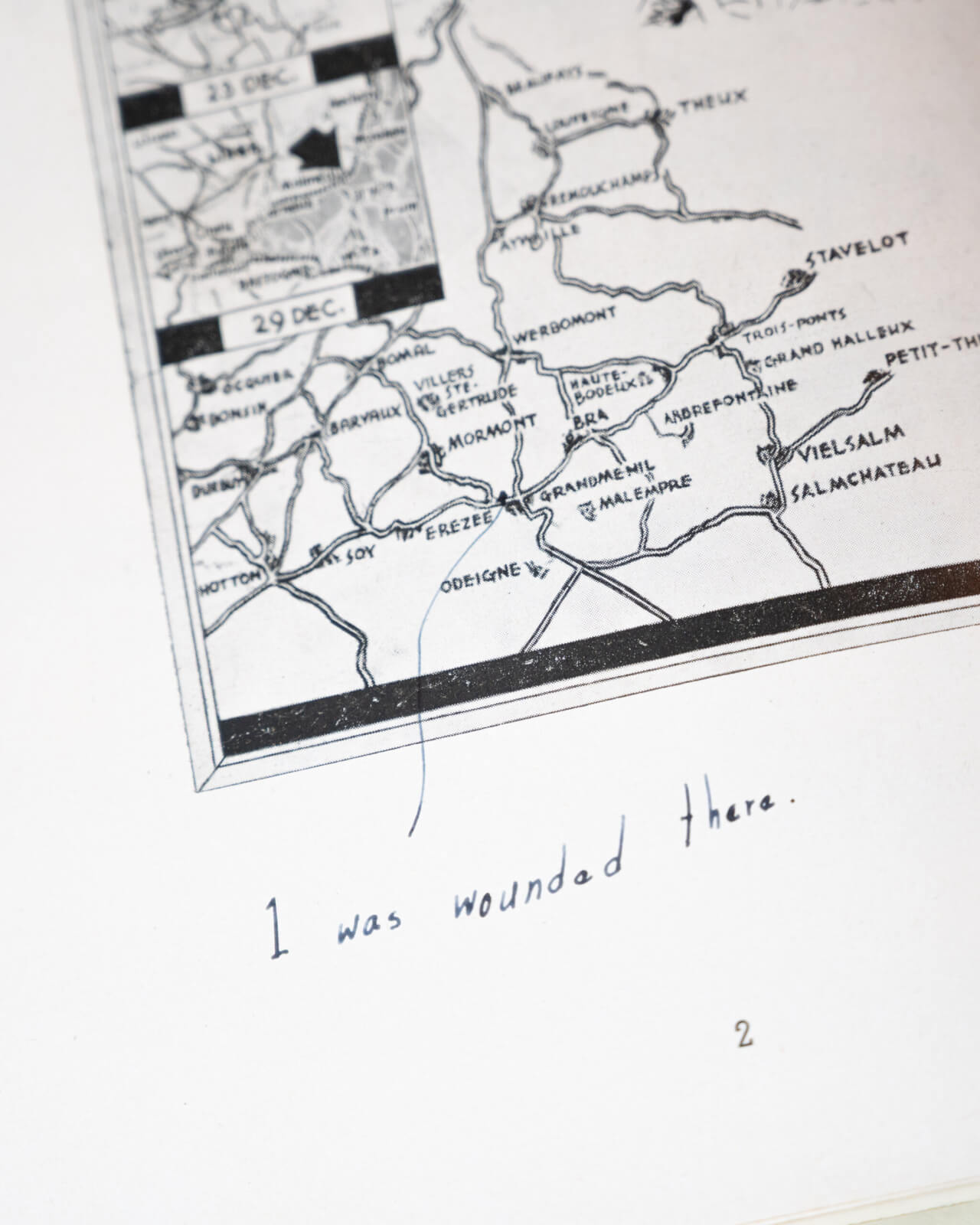

But it was a mission in January 1945 that would pull Brantley from the action.

After getting reports of one of the last German tanks operating in the area, Brantley and several others loaded a Jeep with anti-tank mines in an effort to protect the front lines. The mission would expose them at a heavily observed area; one soldier flagged them down and warned, “you’re gonna have to go like hell to get through there.”

“Unfortunately, he was right,” Brantley said.

An explosion blew the Jeep off the road, pinning Brantley underneath. Having lost consciousness, he only recounts what he was told by survivors thrown clear of the blast. Brantley was severely wounded, and while he was being treated at an aid station, chaos ensued during battle and he was evacuated. Shuffled between medical facilities with no recordkeeping, he was declared Missing In Action for six weeks.

Courtesy photo.

Courtesy photo.

He recovered from a concussion, contusions, broken ribs, temporary paralysis, and voice loss. Turning down limited duty, Brantley requested to rejoin combat with his old unit, where stayed until the end of the war. Occupying the country for several months afterward, he recalled the attitude of the civilians post-war.

“The German population were so thankful that it was over with,” he said. “I’ve had so many of them that actually thanked me for saving them.”

‘Blessed’

Brantley returned to the United States in January 1946 to his bride, and they settled in Columbia, South Carolina. With three children, multiple grandchildren and now great-grandchildren added to their family, he has witnessed three generations rise up in the decades since the harrowing years of World War II.

“I’m blessed just to be here,” Brantley said. “I’ve never considered myself a hero, but I can truthfully say I was honored with my association with a lot of people who were heroes.”

Courtesy photo.

Courtesy photo.

Less than .5% of its veterans are alive today. Because each veteran’s story is “an invaluable national treasure,” Ancestry.com has launched an initiative with the WWII Veterans History Project to preserve history. The “Thank You For Your Story” campaign safeguards 80 veterans’ stories as a lasting measure of appreciation that will influence future generations.